Wieland’s art, deeply political and experimental, engages with feminism, social justice, environmental concerns, and Canadian identity. Decades before these themes became mainstream in contemporary art discourse, she was addressing them head-on, often with a uniquely personal and tactile approach that blended traditional “craft” techniques—quilting, embroidery, and fabric work—with painting and film.

John Reeves, Joyce Wieland in New York, May 1964.

The exhibition, Heart On, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the Art Gallery of Ontario brings long-overdue attention to Joyce Wieland’s pioneering work in film and visual art. Curated by Anne Grace and Georgiana Uhlyarik, the show reaffirms Wieland’s significance as a critical figure in 20th century art, particularly in Canada, but also internationally.

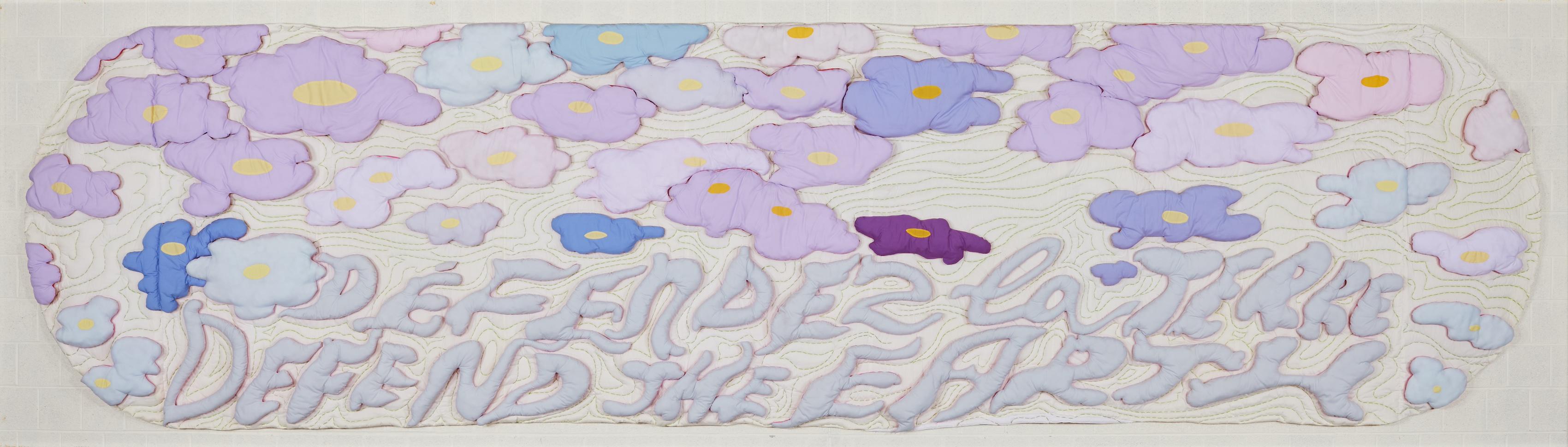

Joyce Wieland (1930-1998), ouvrage: Joan Stewart, Quilting and Embroidery Associates, Défendez la terre, 1972. Ottawa, Conseil national de recherches Canada, commande pour la Bibliothèque scientifique nationale.

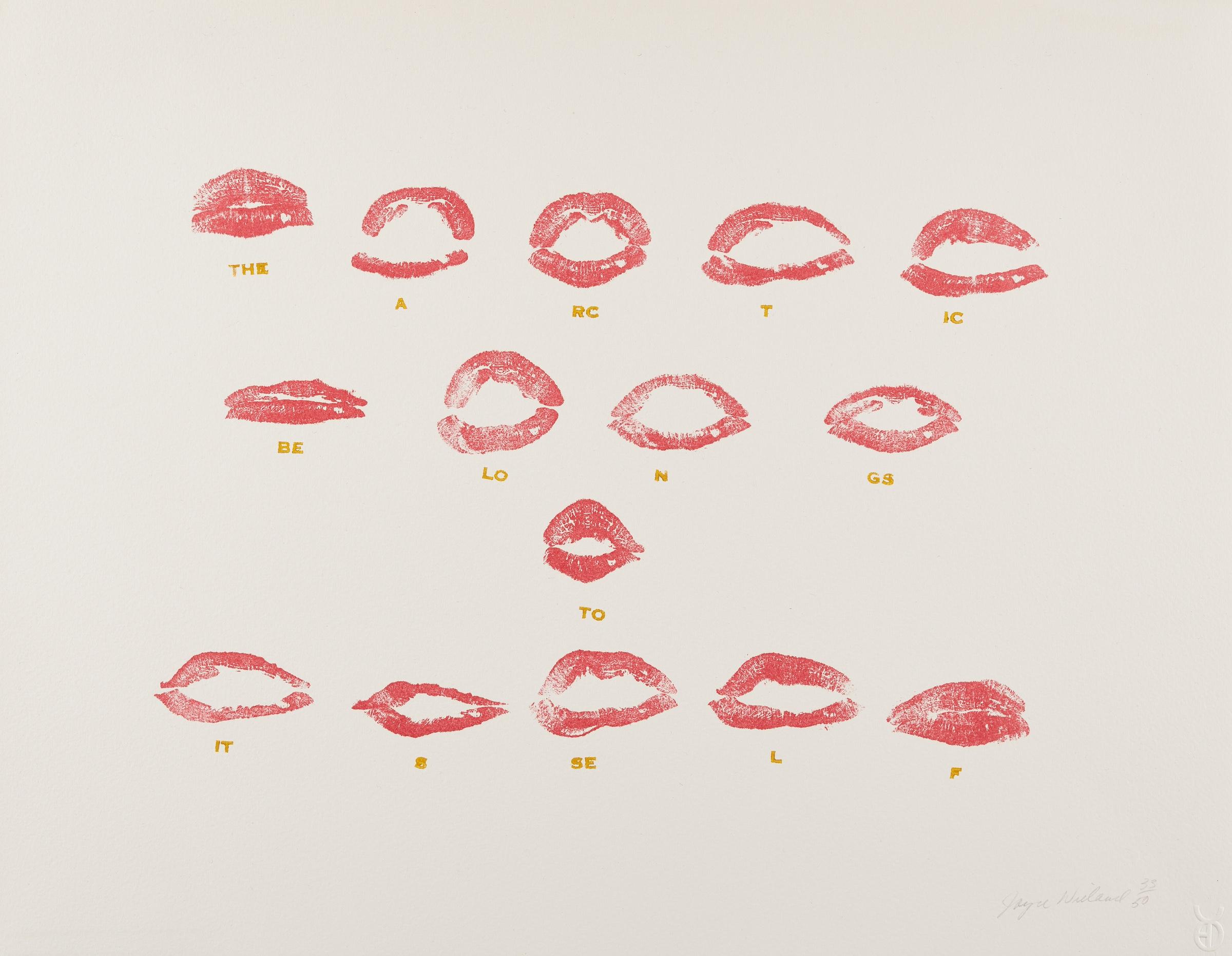

Joyce Wieland (1930-1998), The Arctic Belongs to Itself, 1973. MMFA, Pierre Théberge Bequest.

Her engagement with Indigenous culture, Arctic sovereignty, and American imperialism now feels eerily prescient, making her work more relevant than ever. Defend the Earth (1972) is the largest quilt she ever produced. It’s a field of quilted pastel-colored flowers hovering above a warning message about the planet’s ecology, as well as a wakeup call about the beauty of the Arctic.

The Arctic Belongs to Itself is a seductive print done with her lips that speaks of its concern for Arctic inhabitants vs. the pillaging capitalist forces that wish to destroy it. The Arctic is still a zone of power politics between Canada and the United States.

Joyce Wieland (1930-1998), March on Washington, 1963. Art Gallery of Hamilton, gift of Irving Zucker, 1992.

The exhibition, running from February 8 to May 4, 2025, offers a fresh look at Wieland’s bold artistic interventions. Works such as March on Washington (1963) and her embroidered Canadian flags—each distinct in size and shape, with provocative messages stitched into their fabric—challenge notions of nationalism and technological imperialism.

Her early experiments in film, which she referred to as “filmic paintings,” highlight her ability to merge cinematic techniques with visual art, creating works that pulse with movement and urgency. Combining Pop Art, sarcasm, and politics, Wieland’s 1966 soft sculpture Betsy Ross, Look What They’ve Done with the Flag You Made with Such Care is a forceful warning message, meant to sock it to the viewer.

Joyce Wieland (1930 -1998), Betsy Ross, Look What They’ve Done with the Flag that You Made with Such Care, 1966. Collection of Morden and Edie Yolles.

Wieland’s ability to incorporate humor, whimsy, and intimacy into her activism sets her apart. Pieces like Valentine’s Day Massacre showcase her playful yet sharp commentary, while her 1968 quilts, Reason over Passion / La raison avant la passion, offer a wry critique of political rhetoric. The exhibition also underscores her influence on feminist art, predating works like Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party.

Despite her substantial contributions, Wieland remains underappreciated, particularly in the U.S. This exhibition aims to change that, positioning her as an artist whose vision was not only ahead of her time, but remains strikingly relevant today. Through vibrant pastels, rich textures, and provocative messages, Heart On presents a powerful reflection on national identity, environmental urgency, and the role of art in shaping the future.

As Wieland herself warned in 1971, “Canada can either now lose complete control—or it can get itself together.” Her work compels us to ask: Have we?