Varied by culture, artistic movement, influence, and preferred medium, these Latin American artists might not have much in common, except for the fact that they deserve more recognition for their contributions to the art historical canon. This list is nowhere near comprehensive and is merely the tip of the iceberg. Hopefully, it will inspire readers to explore and celebrate the vast array of Latin American artists.

Marta Minujín, Photo from La destrucción (The Destruction), 1963.

Influenced by the cultural hubs of Buenos Aires, Paris, and New York, Argentinian artist Marta Minujín’s experimental and radical “happenings'' capture the innovation of the 1960s and the decade’s rejection of tradition and complacency. Specializing in participatory performance art, soft sculpture, and video, Minujín explores the nuances of the ephemerality of art. Some of her most notable pieces include, but are not limited to, La Destrucción, 1963 (A participatory piece where fellow artists would either destroy or modify her existing oeuvre), La Menesunda, 1965 (A collaborative large-scale environmental installation reflecting the stimulatory chaos of city streets), and El Partenón de libros, 1983 (A to-scale recreation of the Parthenon constructed from banned books as a celebration of the new intellectual and democratic freedom after the dissolve of the civil-military dictatorship in Argentina). Minujín’s trailblazing works introduced conceptual art to the Argentinian mainstream culture.

Rafael Barradas, Atocha, 1919. Oil on Canvas. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid.

Nurtured in an artistic household and primarily self-taught, Uruguayan artist Rafael Barradas’ innovative work became the platform for other modern art movements. With fingers in many different pies, Barradas explored artistic expression as an illustrator, journalist, scenographer, toymaker, and painter. Best known for the latter, Barradas infused elements of Futurism and Cubism to produce the offshoot movement, Vibracionismo. Aiming to capture the hustle of urban life as if in a single glance, Vibracionismo is characterized by a dynamic movement within a single perspective. The style often utilizes vibrant and emotive brushstrokes. Barradas’ work within this period led to the inception of Joaquín Torres García’s movement, Constructive Universalism. Although he passed away at a young age, Barradas’ oeuvre sent shock waves through the art world.

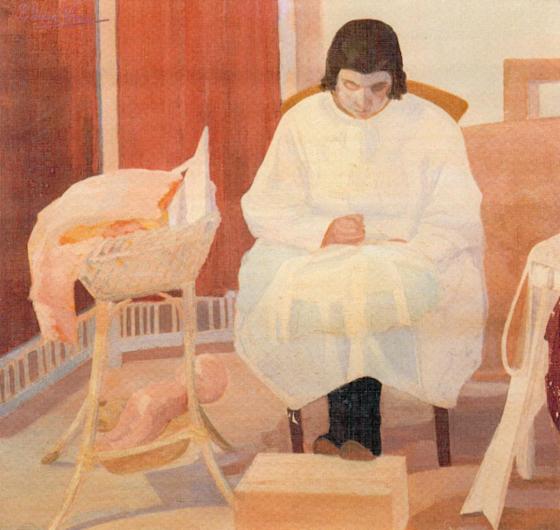

Petrona Viera, La Costura, date unknown. Oil on Canvas. Museo Juan Zorrilla de San Martin, Uruguay.

Despite the lack of representation in art history, Petrona Viera is considered the first professional female artist in Uruguay and one of the dominating figures of the Uruguayan movement, Planismo. Deaf, due to a childhood contraction of Meningitis, Viera learned from private tutors throughout her adolescence. Under the guidance of artists Vincent Puig and Guillermo Laborde, Viera’s undeniable talent propelled her into a professional art career. Viera was greatly influenced by Laborde, a founding member of Planismo—a movement characterized by flat planes of color and interlocking geometric shapes to convey landscapes. Although differing from her tutor in subject matter, Viera celebrated the mundane by exploring domestic life through the lens of Planismo. At twenty-five, she began exhibiting her paintings and, within three years, she held her first solo exhibition. In her later career, Viera dabbled in various mediums including watercolors, engraving, and ceramics. Her contribution to Uruguayan art solidified her as a trailblazing figure which is deserving, if nothing else, of recognition and celebration.

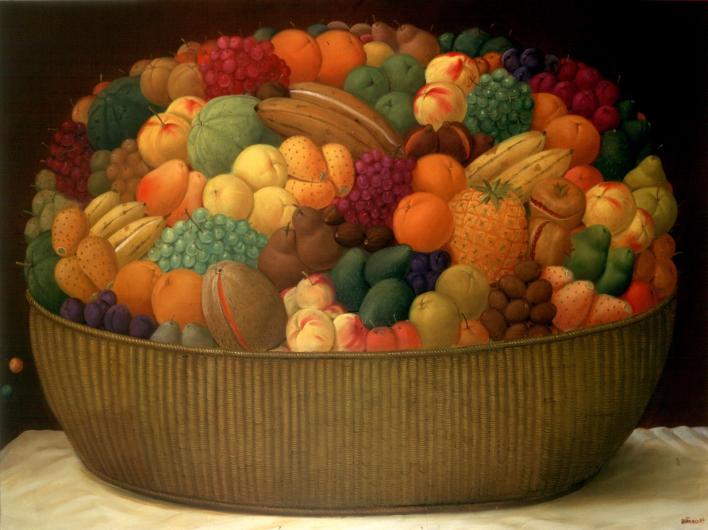

Fernando Botero, Canasta de frutas, 1997.

As one of the only artists to have a movement named after them while they were still alive, treasured Colombian painter and sculptor Fernando Botero cultivated an immediately recognizable and striking style in the mid-twentieth century. A blend of saturated color and rotund caricaturistic figures, Boteroism explores the art of the Old Masters, humor, and socio-political satire. Although his work featuring voluptuous figures are generally easily digestible, his Abu Ghraib series serves as harsh and visceral commentary on the United States contribution to the violence and inhumane torture of Iraqi prisoners in the mid-2000s. In recent years, Botero’s Pope Leon X—with the caption “Y Tho”—became the vessel of a bonafide meme in the mid-2010s, sparking a new generation’s interest in the famed artist’s work.

Doris Salcedo, Installation of Shibboleth at the Tate Modern.

Shaped by the social and political unrest of her home country, Colombian artist Doris Salcedo’s emotionally charged art reflects on personal traumas, loss, and mourning. She explores these themes through sculpture and installation bringing tangibility to the abstract atrocities of war, violence, murder, and the unquenchable grief of those left behind.

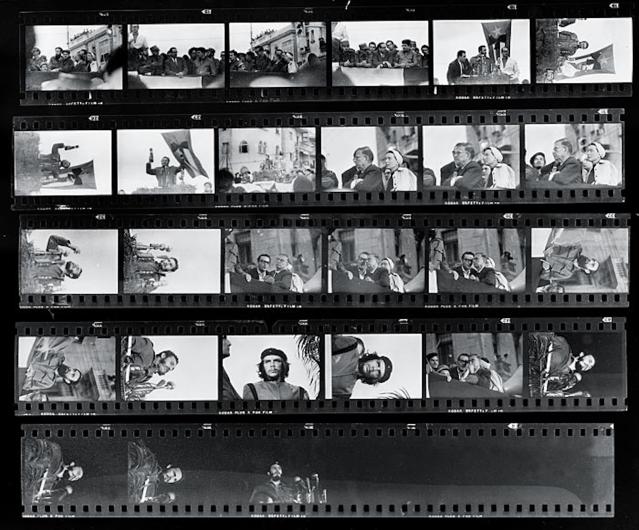

Alberto Korda’s Film Roll from March 5th, 1960.

While you might not know the name Alberto Díaz Gutiérrez—or pseudonym Alberto Korda—you would certainly recognize his work. From humble beginnings, Korda began his artistic career as a photographer’s assistant and climbed the ladder of success from shooting weddings to advertisements to fashion editorials. However, as political upheaval began to sweep Cuba in the 1950s, Korda’s work shifted to document the evolving socio-political climate. He eventually became the primary accompanying photographer of Fidel Castro. Korda is best known for his iconic portrait of Che Guevara and other stunning images of his country's revolution.

Jesús Rafael Soto, Penetrable Amarillo, 1990.

Specializing in Op and Kinetic art, Venezuelan artist Jesús Rafael Soto dazzled the art world with thought-provoking and peculiar sculptures and paintings. Although initially trained under the tenets of post-impressionism, the complete deconstruction of Cubism in tandem with the dream-like quality of Surrealism and other modernist movements ultimately influenced Soto through his professional career. Invested in the combination of mental stimulation and the effect of tangible art, Soto’s ingeniously crafted immersive sculptures allow the viewer to enter a plane of colorful intrigue and fascination. Soto's Work and installations can be found in permanent museum collections around the world, in cities such as Lima, New York, Washington D.C., and Essen.

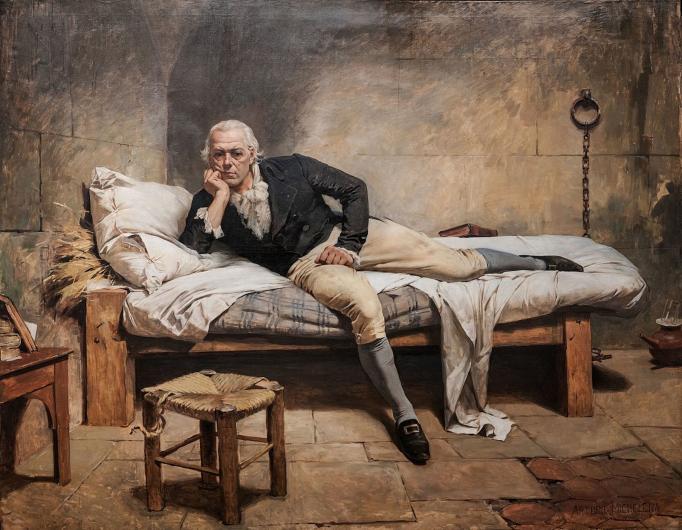

Arturo Michelena, Miranda en La Carraca, 1896. Oil on Canvas. National Art Gallery.

While his life was cut short due to bouts of tuberculosis, Arturo Michelena’s quiet genius gained critical acclaim in Venezuela and France in the mid to late nineteenth century. Innately intrigued by the visual arts, Michelena began painting under the guidance of his father at a young age. In 1885, at twenty-two, he secured a state-sponsored grant to study in Paris, where he enrolled in the Académie Julian and received lessons from Jean-Paul Laurens. In the span of five years, Michelena won a second-class gold medal at the 1887 Paris Salon (The Sick Child), a gold medal in the 1889 Exposition Universelle (The Execution of Charlotte Corday), and illustrated Victor Hugo’s Hernani. Upon becoming ill, Michelena returned to Venezuela in 1892 but still managed to work as the official painter of President Joaquín Crespo until his death six years later. Although a celebrated and seminal figure in Venezuela, Arturo Michelena’s legacy has been stifled by the lack of active academic research and investment in the Latin American community at large.

Marta Minujín, Photo from La destrucción (The Destruction), 1963.

Influenced by the cultural hubs of Buenos Aires, Paris, and New York, Argentinian artist Marta Minujín’s experimental and radical “happenings'' capture the innovation of the 1960s and the decade’s rejection of tradition and complacency. Specializing in participatory performance art, soft sculpture, and video, Minujín explores the nuances of the ephemerality of art. Some of her most notable pieces include, but are not limited to, La Destrucción, 1963 (A participatory piece where fellow artists would either destroy or modify her existing oeuvre), La Menesunda, 1965 (A collaborative large-scale environmental installation reflecting the stimulatory chaos of city streets), and El Partenón de libros, 1983 (A to-scale recreation of the Parthenon constructed from banned books as a celebration of the new intellectual and democratic freedom after the dissolve of the civil-military dictatorship in Argentina). Minujín’s trailblazing works introduced conceptual art to the Argentinian mainstream culture.

Rafael Barradas, Atocha, 1919. Oil on Canvas. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid.

Nurtured in an artistic household and primarily self-taught, Uruguayan artist Rafael Barradas’ innovative work became the platform for other modern art movements. With fingers in many different pies, Barradas explored artistic expression as an illustrator, journalist, scenographer, toymaker, and painter. Best known for the latter, Barradas infused elements of Futurism and Cubism to produce the offshoot movement, Vibracionismo. Aiming to capture the hustle of urban life as if in a single glance, Vibracionismo is characterized by a dynamic movement within a single perspective. The style often utilizes vibrant and emotive brushstrokes. Barradas’ work within this period led to the inception of Joaquín Torres García’s movement, Constructive Universalism. Although he passed away at a young age, Barradas’ oeuvre sent shock waves through the art world.