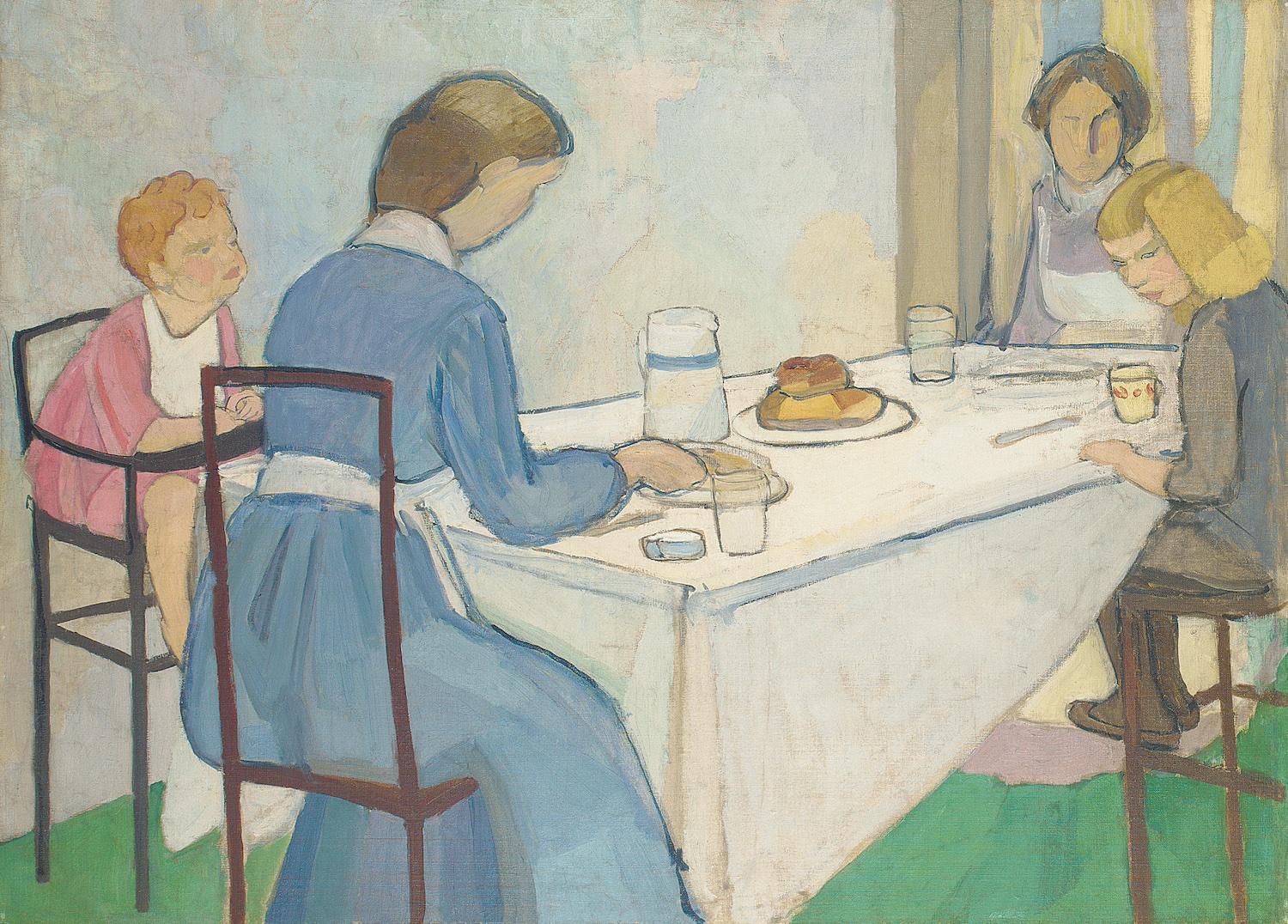

The painting, now known as Iceland Poppies, seems to point to the hands behind the still life. The whole image is about pause, emphasized by the poppies with their narcotic properties, and of course, the poison. When I was in front of the painting, I wondered not what to anticipate (i.e. is someone getting poisoned?), but what had come before. When did Bell buy an antique pharmacist’s jar? Who arranged the table? Were the poppies plucked from the garden or purchased from the florist?

Until recently, it has been somewhat difficult to ask any questions about Bell’s work. The artist is primarily remembered for being a member of the Bloomsbury Group, more so than what she produced within it. Outside of Bell’s home and studio in Charleston, one seldom encounters her paintings, much less her textiles, ceramics, or furnishings. Her work has been displayed mostly in connection to her sister, Virginia Woolf, for whom she designed book covers.