A new fresco uncovered from a house in Regio IX (region 9) at the city of Pompeii depicting Paris of Troy persuading Helen to run away with him, thus providing the catalyst for the Trojan War. These new frescoes are some of the finest examples to date and showcase details often lost over time in other ancient paintings.

In the world of archaeology, 2024 was a busy year with many discoveries and breakthroughs in the study of humankind’s past. Countless archaeological projects pushed chronological boundaries, changed our perspectives, and quite literally rewrote history with their amazing work. From newly discovered cave paintings in Indonesia— now the world’s oldest— to rewritten narratives at long-known sites such as Pompeii, 2024 proved that there is always more to discover and learn. Read on below for 10 examples of some of the incredible archaeological news stories of the past year.

New research published by an international team of scholars has shown that rice beer was being brewed 10,000 years ago at the Shangshan archaeological site in the Zhejian Province in China. By conducting analyses on ceramic vessels recovered from the site, the research team was able to identify microfossils of starch grains and phytoliths, mold, and yeast. The combined presence of these suggested that rice, a staple plant for the people of this region, was being used to create alcoholic beverages, specifically an early type of beer.

While rice alcohol itself is not a new discovery, this research shows that the Shangshan people are now the earliest known innovators of this kind of fermentation technology in East Asia. The study furthermore showcased how specific environmental factors were also critical for the development of this particular method of fermentation and made important inferences about the evolution of agriculture and rice domestication in China at this time.

Image: Evidence for 10,000 year old rice beer found on ceramic vessels at the Shangshan archaeological site is now the oldest known example of rice fermentation of this kind in East Asia.

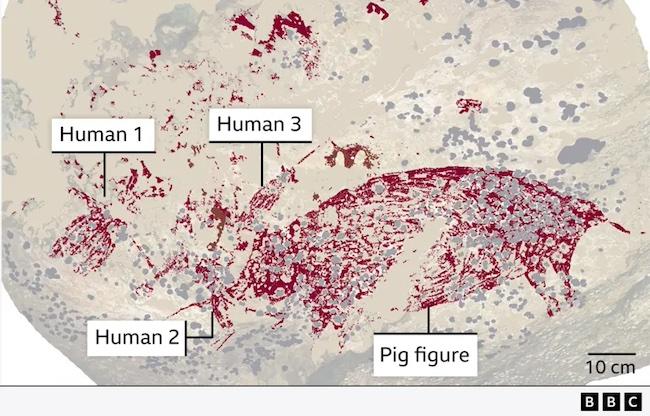

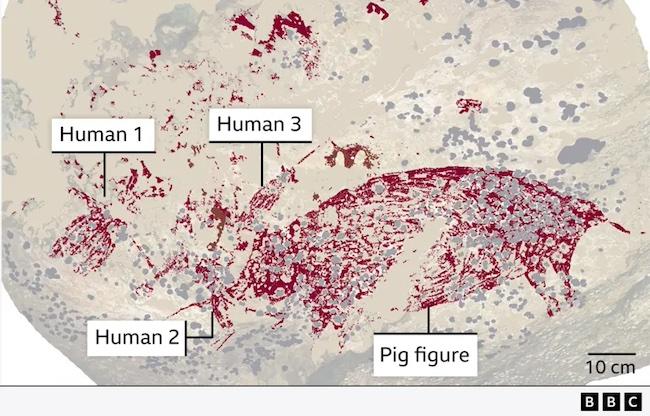

On the Indonesian Island of Sulawesi, the age of human artistic creation was pushed back by more than 5,000 years when scientists uncovered a previously unknown cave painting. The painting, depicting a wild pig and three humanoid figures, is about 51,200 years old, predating the previously known oldest cave art by at least 5 millennia.

Like other examples of early cave art, this new painting is fabulous in nature and depicts a complex pictorial example of storytelling, showcasing that early humans were conveying and transmitting abstract terms and ideas through visual language. Scholars of human prehistory posit that the act of storytelling is likely much older than 51,200 years. However, when words are not preserved, archaeological evidence such as these new Indonesian cave paintings are our best way to make intangible history tangible once again.

This discovery not only helps flesh out the murkiest epochs of humanity, but it also allows us to thoughtfully reflect on the deep relationship between humankind and the creation of art to represent our thoughts and feelings across time and space.

Image: An augmented image of the newly discovered and now oldest cave painting in the world from Indonesia. The painting depicts three human figures around a pig.

A UNESCO world heritage site, Çatalhöyük has constantly pushed the boundaries of what we know about the rise of organized human society, and now, it has also provided us with evidence of the rise of baking.

In March, archaeologists at the site uncovered the world’s oldest example of bread, dating to around 6600 BCE. Found near the ruins of a destroyed oven, a palm-sized, round, spongy residue was excavated along with remains of wheat, barley, and pea seeds. Analyses concluded that the residue was uncooked, fermented bread.

What is more, a finger indentation was identified in the center of the residue, evidence of the ancient baker’s presence before the uncooked loaf was abandoned. The discovery is the first of its kind and presents a new terminus post quem for the introduction of fermented baking amongst humans.

Image: Archaeologists discovered an example of 8,600 year old fermented, uncooked bread at the UNESCO World Heritage site, Çatalhöyük. This discovery is the oldest example of leavened bread in the world, predating previous examples from Egypt by hundreds of years.

A newly unearthed theater and temple complex at the Peruvian archaeological site of La Otra Banda, Cerro Las Animas were discovered in June of this year, expanding both our understanding of religion in the region, as well as the timeline of ancient Peru.

Dating to around 4,000 years ago, the building and material remains at this new site consist mainly of mud and clay walls, some with evidence of staircases and carved reliefs. Based on iconographic dating, archaeologists believe that the site was in use during the early Initial Period (2000-900 BCE), pre-dating Peru’s most famous archaeological site, Machu Picchu, by nearly 3,500 years.

While the discovery of buildings this old is exciting in and of itself, what is most significant about this find is the potential it has to shed light on the development of religious ideas and practices during this period of Peruvian history.

The organization of the buildings and the iconography carved into the walls may help us to better understand the dawn of institutionalized, complex religion in the Andes region, the reasoning for which still presents question marks for scholars.

Image: Walls from what is thought to be a 4,000 year old ceremonial temple in Peru.

2024 was a busy year for Pompeii, as multiple new excavation projects in still-buried regions of the city uncovered both exquisitely preserved materials and further examples of the immense human tragedy that occurred in 79 BCE. Some of the discoveries have included newly uncovered frescoes, many of which are considered some of the best examples of early Roman imperial painting found to date and stand to contribute much to what we know about Roman tastes for art and the production of such things.

Elsewhere at the site, new DNA testing of human remains has also upended many assumptions about the tragedy and its victims. When the eruption victims began to be rediscovered in the 1800s, many were found in groups or pairs, frozen in time in tragic positions huddled together, or covering one another from the debris falling around them.

Previous scholarship assumed these groupings must have been couples or familial relations. For instance, one famous example has always been thought to be a mother holding her child. New DNA testing, however, has shown that many of the individuals shared no genetic relations whatsoever.

The mother and child actually turned out to be an adult male and a genetically unrelated child. This new data thus allows us to tell more nuanced narratives about those lost in the eruption and encourage more thoughtful considerations of archaeological evidence based solely on assumed gender and familial relationships from modern-day expectations.

Image: A new fresco uncovered from a house in Regio IX (region 9) at the city of Pompeii depicting Paris of Troy persuading Helen to run away with him, thus providing the catalyst for the Trojan War. These new frescoes are some of the finest examples to date and showcase details often lost over time in other ancient paintings.

A Roman necropolis dating to the 1st-3rd centuries CE and utilized for infant burials was unearthed in Auxerre, France over the summer. More than 250 infants were located within the cemetery, and the diversity of the manner of burial stands to shed some light on how families in antiquity made decisions regarding the loss of young life.

The majority of the infants found within the necropolis were younger than one year old, and even included the burials of stillborn and miscarried children. As was typical of Roman cities, the necropolis was outside the official confines of the town of Autessioduro. However, scholars also note that it was typical in ancient Gaul (what the Romans called much of modern-day France) to separate a portion of the larger city necropolis for the very young.

The burial containers for the infants at Autessioduro varied greatly, ranging from wooden coffins, to ceramic vessels, to textiles and even fragments of large containers, like amphorae.

This diversity in container, as well as grave goods and the very construction of the tombs, indicates that a great deal of individual and familial choice went into the formation of these final resting places and helps us to better understand the lives of the very young in the Roman empire, even if those lives were cut short.

Image: Overview of the excavation of the infant necropolis of the Roman town Autessioduro (modern day Auxerre, France). More than 250 infant burials were located.

Ranging from simple geometric patterns to complex figural designs, the famous Nazca Lines in Peru were carved into the earth between 500 BCE and 500 CE. Made by tracking shallow depressions into the ground, thus exposing different colors of soil, the number of glyphs and lines totalled about 358 as of 2022.

Recent work this year, however, has nearly doubled that number of lines as archaeologists utilizing AI systems to analyze drone photography have uncovered another 303 previously unknown geoglyphs. Many of the new lines are natural in theme, depicting animals like parrots, monkeys, and whales, while others display more complex forms, such as one example of a human figure holding a decapitated head.

While earlier theories thought the Nazca Lines were astronomically or cosmologically significant, more prevalent conclusions about their purpose tie them to religious or ritual needs and actions of the Nazca peoples. These additional 303 new geoglyphs will certainly aid those scholars working on them to help us better understand this era of Peru’s past.

Image: One of the 303 newly discovered geoglyphs from the famous Nazca Lines ensemble in Peru. The new images were located with the help of AI analyses of drone photography.

A compelling new theory about the origins of the wheel has been put forth by a collaborative team of historians and engineers at Columbia University, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and the Georgia Institute of Technology. Prior to this work, the prevailing theory has been that the wheel was invented around 4000 BCE in relation to the development of the potter’s wheel in Mesopotamia.

This new theory, however, links the wheel’s creation to copper miners in the Carpathian Mountains as a means to move ore in wheeled devices. The research team utilized design science and computational mechanics to investigate how these early miners could have gradually adapted logs stripped of their limbs into wheel and axle systems in order to navigate the narrow tunnels of a mine.

A demand for greater maneuverability is critical to this theory, and the researchers outlined three stages of development that would have led from log rollers to wheel and axle carts over the span of about 500 years. This theory emphasizes a more nuanced approach to technological development involving trials, adaptations, and environmental influences as the main drivers of change, rather than more popularized accounts of spontaneous invention.

Image: The Ljubljana Marshes (Slovenia) wheel with an axle. Currently, this is the oldest known wooden wheel and axle, dating to roughly 5,100-5,350 years ago. License

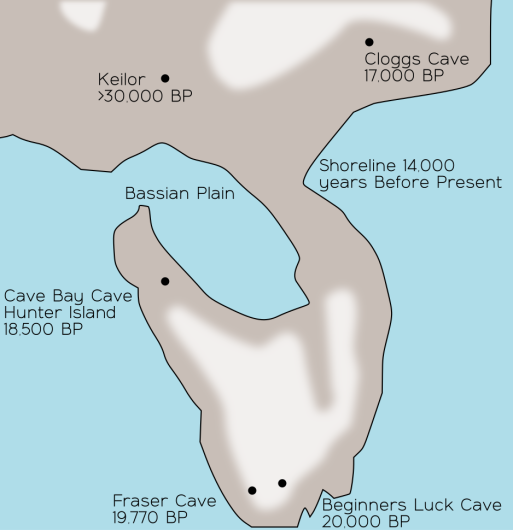

New research led by scholars at the University of Cambridge has identified evidence that the earliest human activity in Tasmania is older than previously thought. By studying the presence of charcoal and changes in vegetal pollen within mud cores from Three Hummock Island and Clarke Island, researchers have concluded that early inhabitants of Tasmania were clearing forests by burning them and introducing new vegetation earlier than prior evidence suggested.

The two islands are both now within the Bass Strait, the waterway between Australia and Tasmania. However, 12,000 years ago, both landmasses were part of an exposed land bridge when sea levels were much lower. This finding pushes back the inhabitation of Tasmania by about 2,000 years, to 41,6000 years ago, and also posits that the Palawa/Pakan peoples who settled the area were, at that time, the southernmost peoples in the world.

Image: Map showing the shoreline of southeastern Australia and Tasmania 14,000 years ago. The Great area indicates the presence of a land bridge between the two before sea levels rose. License

A newly discovered sunken vessel at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, estimated to be from the 13th or 14th century BCE, is challenging what we previously thought about maritime history. The 3,300-year-old wreck is now not only one of the oldest wrecks ever found, but considering it was discovered about 56 miles from shore, it is now also the oldest found so far from land in the eastern Mediterranean.

Prior scholarly consensus was that at this time, ships tended to jot along the coast going from port to port within sight of the shore, rather than venturing out into the open sea for trading. This vessel, however, would have only been able to see the vast horizon line as far out as it was, which suggests that Bronze Age sailors were far more advanced in navigational skills than previously thought.

As the vessel was also so deep in the water (5,906 feet), the wreck was relatively undisturbed and still contained many intact vessels likely containing oil, wine, or other agricultural products. Two jars have been removed from the ship for study, while the remainder of the materials and the ship itself have been left in the sea for future study.

Image: Two jars of agricultural material removed from the 3,300 year old shipwreck in the eastern Mediterranean. The ship is the oldest ever found so far from shore in this part of the world.

New research published by an international team of scholars has shown that rice beer was being brewed 10,000 years ago at the Shangshan archaeological site in the Zhejian Province in China. By conducting analyses on ceramic vessels recovered from the site, the research team was able to identify microfossils of starch grains and phytoliths, mold, and yeast. The combined presence of these suggested that rice, a staple plant for the people of this region, was being used to create alcoholic beverages, specifically an early type of beer.

While rice alcohol itself is not a new discovery, this research shows that the Shangshan people are now the earliest known innovators of this kind of fermentation technology in East Asia. The study furthermore showcased how specific environmental factors were also critical for the development of this particular method of fermentation and made important inferences about the evolution of agriculture and rice domestication in China at this time.

Image: Evidence for 10,000 year old rice beer found on ceramic vessels at the Shangshan archaeological site is now the oldest known example of rice fermentation of this kind in East Asia.

On the Indonesian Island of Sulawesi, the age of human artistic creation was pushed back by more than 5,000 years when scientists uncovered a previously unknown cave painting. The painting, depicting a wild pig and three humanoid figures, is about 51,200 years old, predating the previously known oldest cave art by at least 5 millennia.

Like other examples of early cave art, this new painting is fabulous in nature and depicts a complex pictorial example of storytelling, showcasing that early humans were conveying and transmitting abstract terms and ideas through visual language. Scholars of human prehistory posit that the act of storytelling is likely much older than 51,200 years. However, when words are not preserved, archaeological evidence such as these new Indonesian cave paintings are our best way to make intangible history tangible once again.

This discovery not only helps flesh out the murkiest epochs of humanity, but it also allows us to thoughtfully reflect on the deep relationship between humankind and the creation of art to represent our thoughts and feelings across time and space.

Image: An augmented image of the newly discovered and now oldest cave painting in the world from Indonesia. The painting depicts three human figures around a pig.

Danielle Vander Horst

Dani is a freelance artist, writer, and archaeologist. Her research specialty focuses on religion in the Roman Northwest, but she has formal training more broadly in Roman art, architecture, materiality, and history. Her other interests lie in archaeological theory and public education/reception of the ancient world. She holds multiple degrees in Classical Archaeology from the University of Rochester, Cornell University, and Duke University.