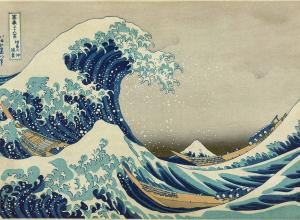

The exhibition is organized by themes: history, portraiture, genre, landscape, and still life. This curatorial choice aims to show how photography initially developed by following, and then challenging, the themes that were commonly used by painters. Since the 17th century, the British and French academies had established a hierarchy for painting genres based on their cultural and social value. Historical paintings (religious, mythological, and allegorical) were the most praised followed by portraits and scenes of daily life. Landscapes, cityscapes, and still life were at the bottom of the hierarchy. Landscapes and still life were understood as no more than a copy of real life, whereas historical paintings and portraits showed the essence of the world and its people. Photography challenged this hierarchy. Due to the bulky equipment and the long exposure times that were characteristic of the initial photographic process, landscapes and still lives were the easiest themes to shoot as they did not require a person to remain still for the time it took for the plate to develop.

Peter Henry Emerson, Gathering Water Lilies, 1885, Platinum print. Collection of Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg

Upon seeing the first daguerreotype around 1840, the French painter Paul Delaroche (1797-1856), declared: “From today, painting is dead.” Painting did not die that day, but photography was born, disrupting the world and its social order through the creation of new ways to see, understand, and explore. The exhibition From Today Painting is Dead at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia presents 250 early photographs created by French and British photographers between the 1840s and 1880s. The exhibition focuses on the early years of photography, all of which are on loan from the private collection of Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg. The collection includes works by William Henry Fox Talbot, Roger Fenton, Gustave Le Gray, and Julia Margaret Cameron.

William Henry Fox Talbot, Articles of China, 1844. Salt print from calotype negative. Collection of Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg.

Roger Fenton, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, Salted paper print.

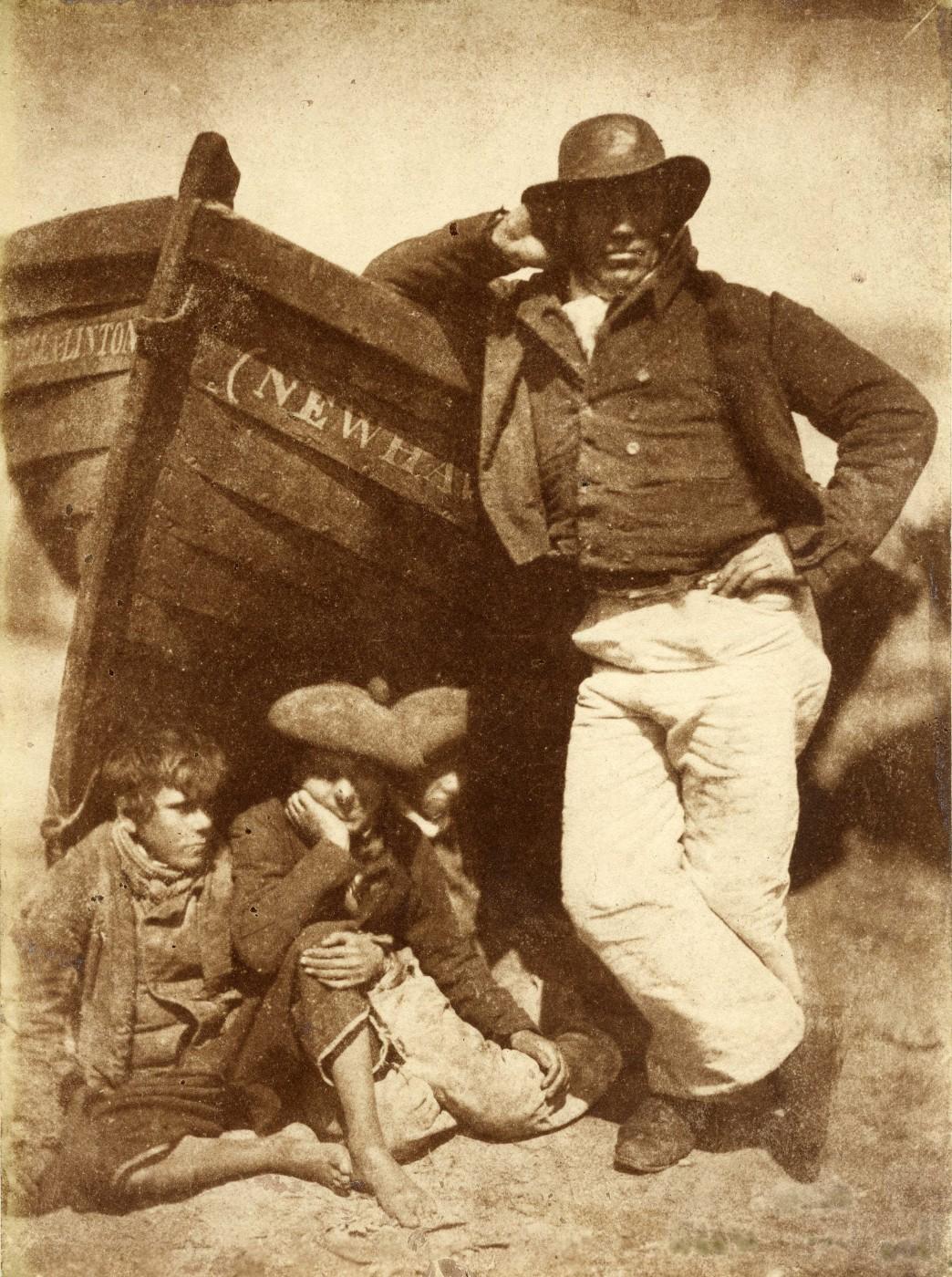

Among the most interesting images presented in the first section—history—the photograph The Valley of the Shadow of Death (1855) by Roger Fenton (1819-69), one of the first Western war photographers, stands out. Fenton, sponsored by the London publisher Thomas Agnew & Sons, left Britain in autumn 1854 to cover the Crimean War (1853-56). Fenton arrived in Crimea in 1855, after all of the major battles had already concluded. Despite the fact that his photographs showed no ongoing battles and that the long photographic exposure required only allowed him to produce images of stationary objects, his photographs were significant because they eloquently conveyed war’s desolation and despair.

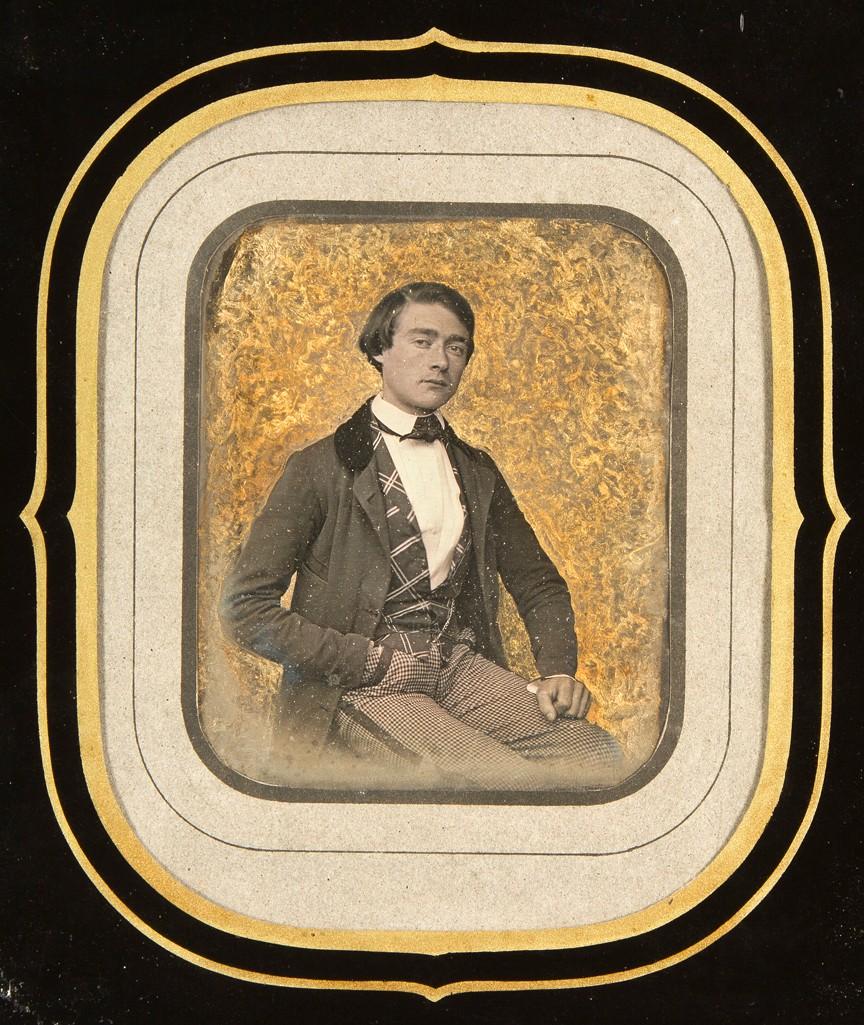

The second and third sections—portraits and genres—show the growing relationship between the 19th-century middle class and the photographic medium. The middle class who could not afford painted portraits of their families turned to photography. Photographic portraits became so popular that by the early 1850s Parisian studios were producing more than 100,000 per year. During the late 1800s, post-mortem photographs were also very common as these images were keepsakes for those families who wanted to remember their deceased loved ones. Furthermore, photographic scenes of daily life in the countryside, such as Gathering Water Lilies by Peter Henry Emerson, began to substitute the expensive landscape paintings and adorn the walls of middle-class homes.

Adolphe Braun, Vallee de Chamonix, c. 1870, Carbon print. Collection of Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg.

From Today Painting is Dead is an unmissable exhibition as it reveals how photography was not only a disruptive innovation in the art world but a revolutionary, popular tool that allowed people to record events, people, places, and objects.