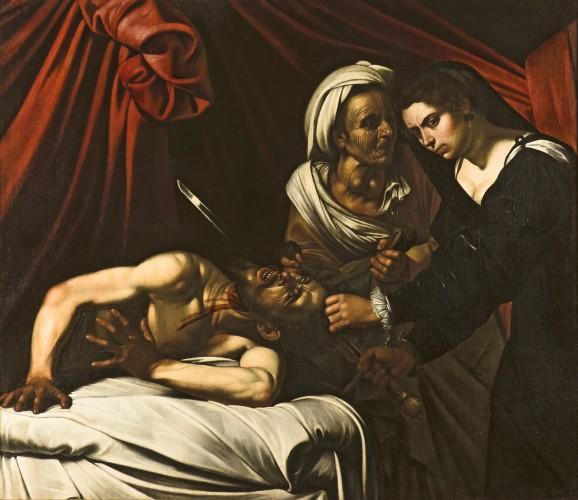

Whatever skill Flemish painter Louis Finson lacked as an artist he made up for as a dealer, admiring, owning and trading numerous works by Caravaggio. Among them was Judith and Holofernes, depicting a scene from the Old Testament Book of Judith in which the beautiful widow learns of Syrian General Holofernes’ plan to raze her home city of Bethulia. While he’s drunk, she seduces, then slays him.

Caravaggio painted two versions of the scene. The first was rediscovered in 1950 and is currently on view at National Gallery of Ancient Art in Rome. Employing a brighter palette, the composition is mainly the same, including the slayer and her victim, as well as Judith’s servant. In that version, painted in 1598, Judith recoils from her act. In the newly discovered version, the palette darkens, in keeping with the artist’s work from this period. Judith does not recoil, but leans into her bloody task, turning a sinister gaze on the viewer.