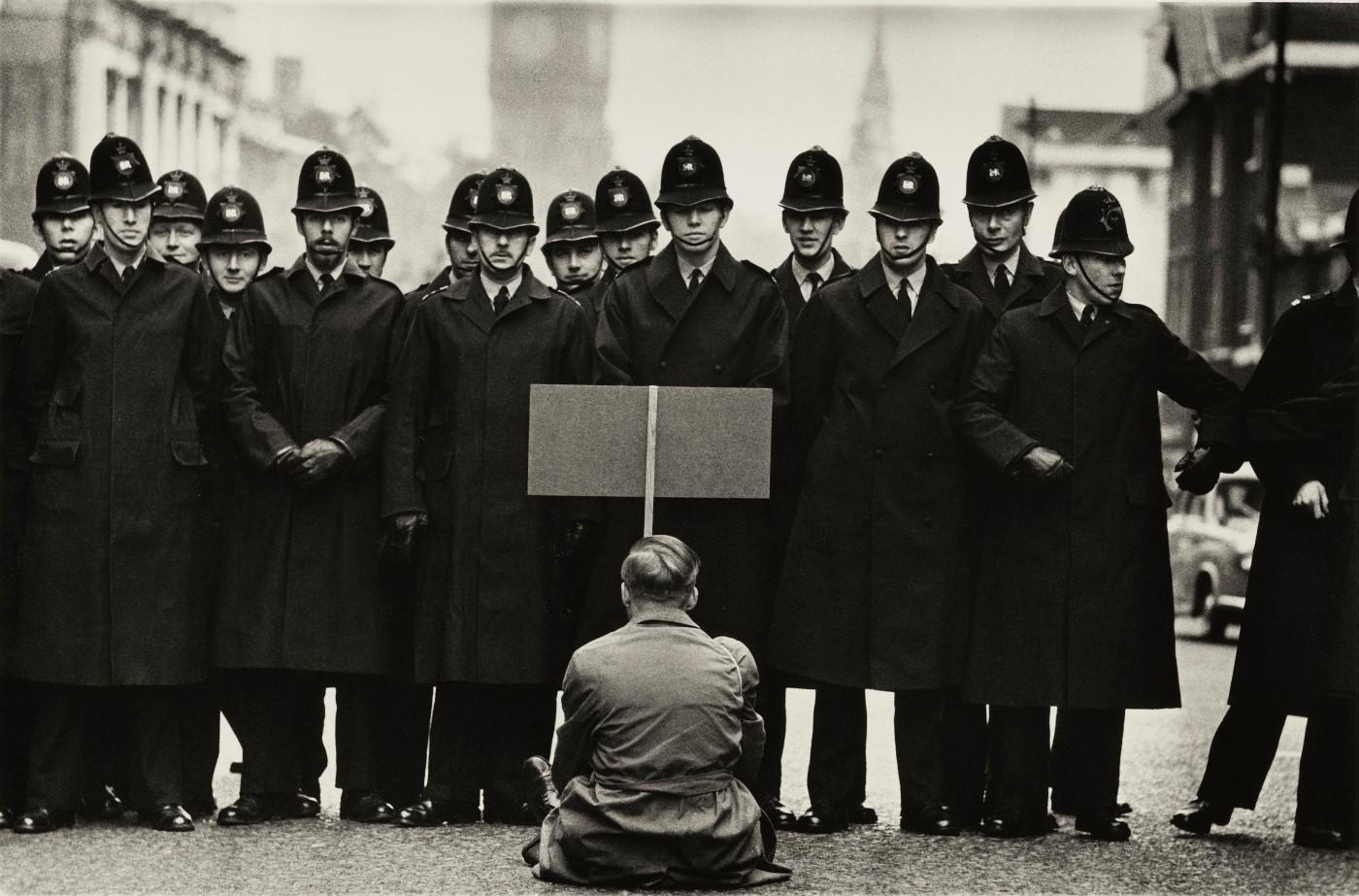

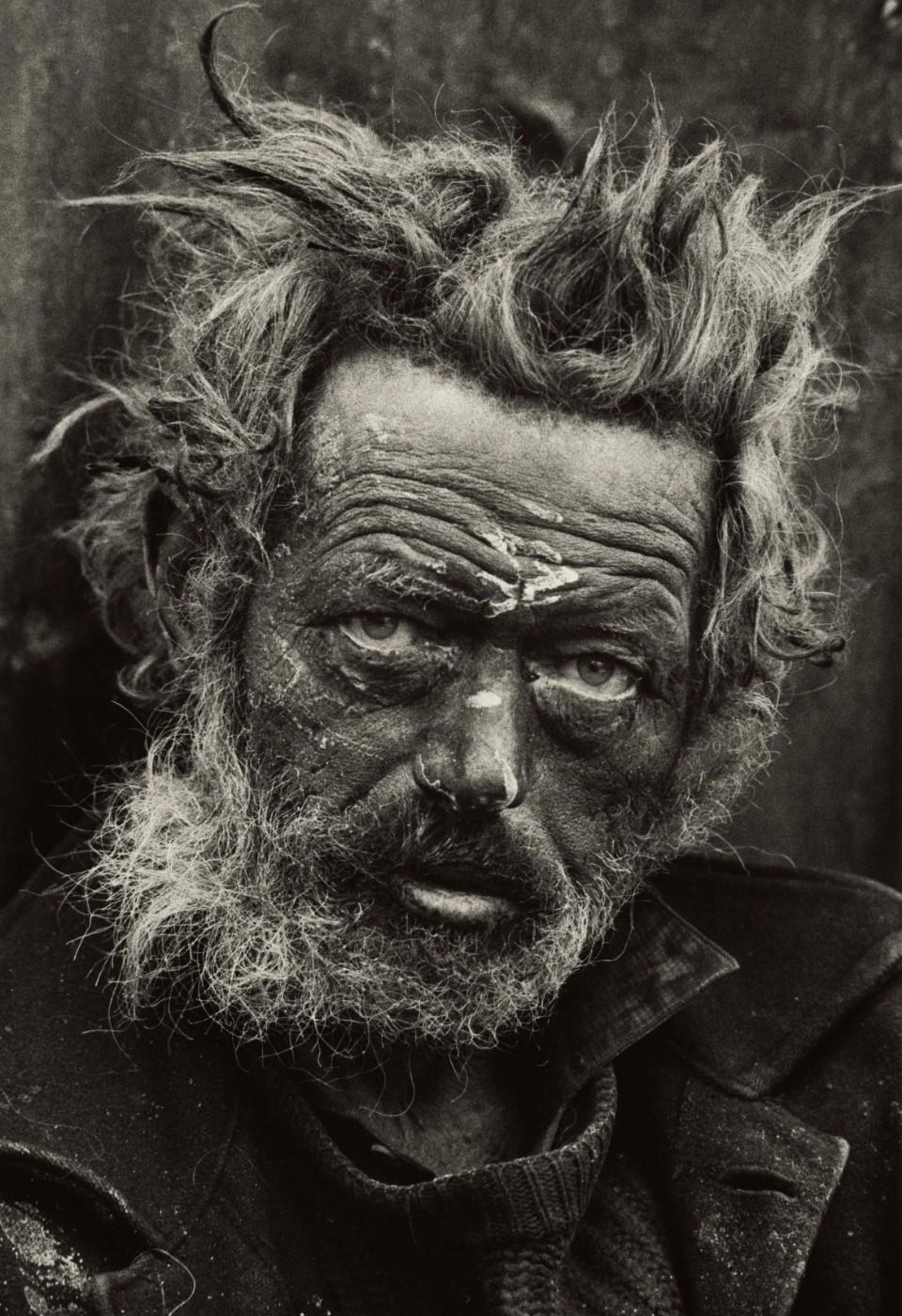

Haunting is the word being used to describe the retrospective dedicated to Sir Don McCullin on view at the Tate Museum in London through May 6. McCullin, born in London in 1935, has spent his life behind a camera, covering some of the most brutal conflicts of the 20th century: Vietnam, Northern Ireland, Biafra, and Cambodia, just to name a few. One of his most famous shots of the Vietnam War is the portrait of a shell-shocked American soldier after the Battle of Hue in 1968. The wide-eyed soldier, with his dirty hands holding the rifle, shows the destruction that war brings to the human mind. But wars, for McCullin, are not just the ones fought on battlefields, but also the social conflicts that we can find in our daily lives: homelessness, mental illness, poverty. His photographs of the homeless of London, for instance, show a different city from the one we usually see in the media; one that thrives on contradictions: poverty and luxury, the famous and the forgotten.

Yet, not all of McCullin’s photographs are about conflict. Since the 1980s, he has devoted his skills to landscape and still life photography. These subjects seem to bring him peace, or at least to distract his mind from the painful memories of what he experienced in the past. “I am tired of guilt,” he says, “tired of saying to myself: ‘I didn’t kill that man on that photograph, I didn’t starve that child.’ That’s why I want to photograph landscapes and flowers. I am sentencing myself to peace.’”