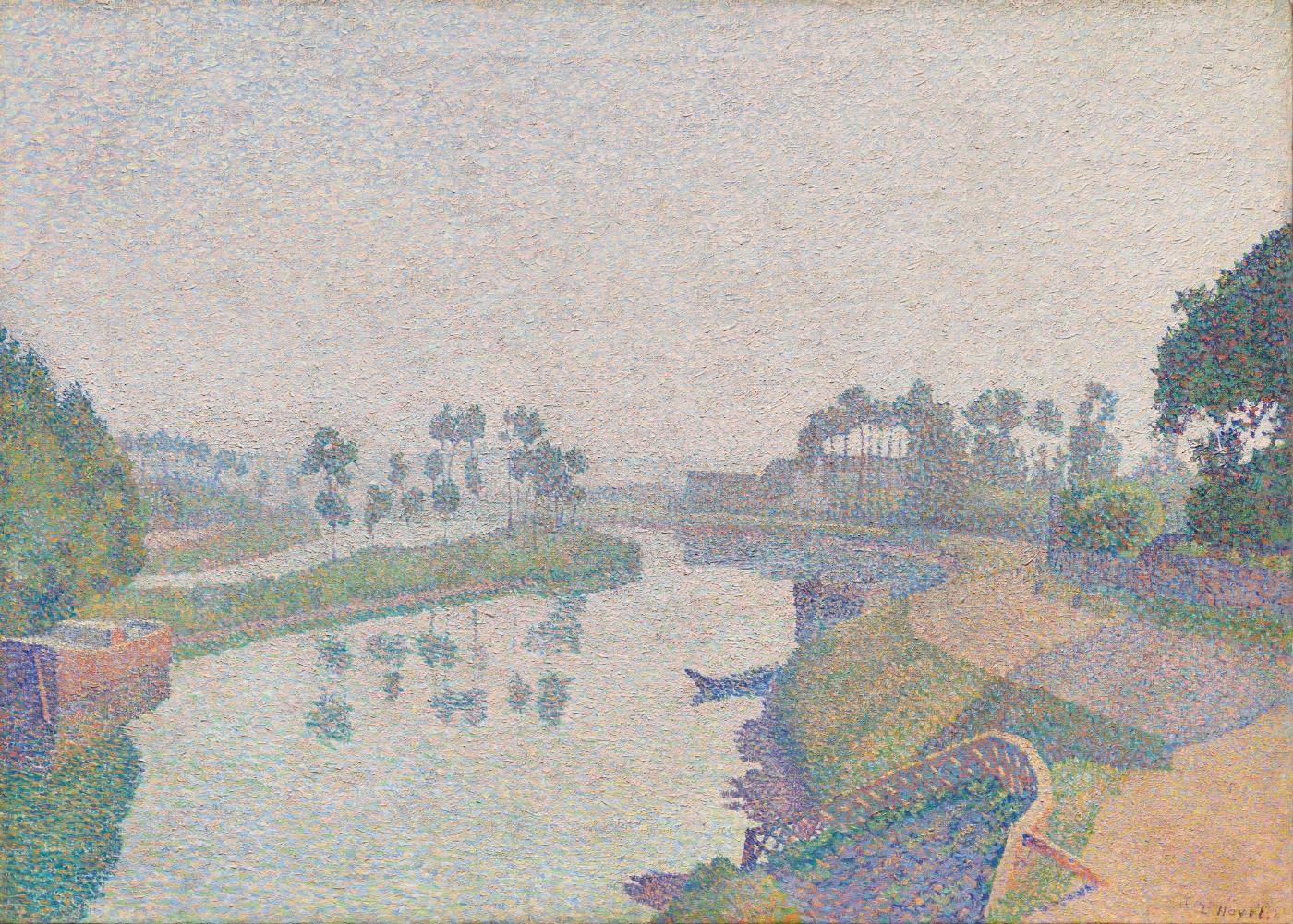

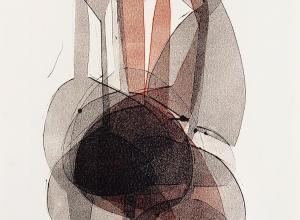

Louis Hayet, Banks of the Oise at Dawn

One of the artist’s finest paintings and a superb example of neo-impressionism

Louis Hayet painted Banks of the Oise at Dawn (1888) in the radically new style of neo-impressionism, also known as pointillism or divisionism, during the early years of the movement. First developed around 1885–86 by Georges Seurat, Camille Pissarro and others, neo-impressionism aimed to bring more order, clarity and luminosity to impressionism by painting in a systematic manner using scientific color theory. The neo-impressionists invented a technique of applying color in small dots or dashes, theorizing that the divided tones would optically unite into a single, powerful hue when viewed at a normal distance.

Hayet was born and raised in Pontoise, a small town about 25 miles north of Paris along the Oise River. Signs of neo-impressionism are evident in Hayet’s paintings as early as 1886, and his technique was well developed by 1888, the year he painted Banks of the Oise at Dawn. The painting’s surface is covered with a network of small, delicate strokes of color ranging from the complementary contrast of blue and orange in the foreground to the whites, pinks and blues in the sky.

Hayet was deeply involved in contemporary theoretical debates and researched color theory. He developed a color chart that incorporated gray tones, an original idea for which he received considerable critical praise. He also saw parallels between color harmonies and music, and he used color to evoke a range of emotional moods in his paintings. Scholars consider Banks of the Oise at Dawn an outstanding example of Hayet’s method of combining complementary colors with gray tones.

This painting enriches the CMA’s overall representation of 19th-century French landscape painting, forming both a complement and an instructive comparison to works by Eugène Boudin, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne and Vincent van Gogh. Banks of the Oise at Dawn is on view in gallery 222, Nancy F. and Joseph P. Keithley Gallery of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Art.