Early this February, Houston Metro announced the installation of commemorative seat covers to honor Rosa Parks on her birthday. Unfortunately, though perhaps unsurprisingly, the covers struck a nerve—particularly in the Twitter-sphere.

Art News

This author has been to a number of museums in the world and never has she found a gem as hidden as the Walters Art Museum. Tucked away in a corner of Baltimore, the Walters is the kind of museum this author would love to take her mother and father to visit.

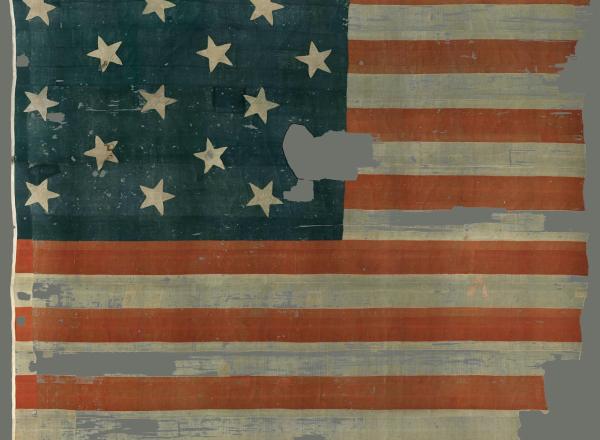

Skeptics of the American Dream likely will consider Emanuel Leutze’s masterpiece depicting George Washington crossing the Delaware River to be a propagandistic romanticizing of America, a work unworthy of praise in the twenty-first-century.

Devastating consequences within the context of science and medicine are unfortunately nothing new to members of the Black population in colonial spaces. This is particularly evident in the Western art history of medical illustrations that feature Black people.

Western art history is filled with colorful characters, whose statuses as heroes or villains can change based on the mores of our current society. The "Reframed" column is not a politically leaning publication. Yet it would be naive not to recognize that we exist in politically charged times.

Easily the most famous depiction of famine in art history is Vincent van Gogh’s 1885 oil painting, The Potato Eaters. At the time of its creation, the phrase "potato eater" was considered pejorative in both Dutch and German.

Midway through October, tech experts Anthony Bourached and George Cann were prepared to unveil their AI-generated recreation of a lost Picasso at London’s Deeep AI Art Fair, when they received a letter from the U.K. side of Picasso’s estate demanding they cease and threatening legal action.

Museum-goers, this author included, are often guilty of walking past still life paintings of food, dismissing them as dull and anodyne. Yet, taking in the context of when they were created, these works of feasts and even ordinary fare are often as political as they are historical.

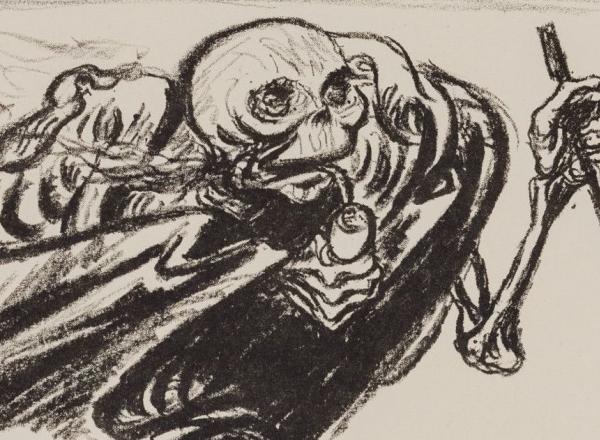

It is an understandable human instinct to treat any crisis as if it were the first of its kind. A century ago, those fears revolved around a widening gap between rich and poor, a global pandemic, and a growing loss of community. Sound familiar?

Upon its creation, Quidor’s painting was widely panned by art critics for being too dark and focusing more on the woodland nature than on the chase. In many ways, this was a clever choice by Quidor, whose perspective reveals the two men for what they are: immature characters fighting over a young woman who is attracted to neither of them.