“Women were important to Kirchner’s creative drive and his girlfriends, Doris (Dodo) Grosse and Erna Schilling, in particular, were muses who inspired him to make some of his most memorable works,” curators Jill Lloyd and Janis Staggs told Art & Object over a joint email correspondence. “His source of creativity was fundamentally grounded in the feminine, and as he put it, ‘The work originates in impulse, in ecstasy.’”

There is a strong link between Kirchner’s romantic relationships with women and his artistic output. In fact, he likened sexual relations to artistic creation, as both were evidently highly inspirational. “Often, I got up in the midst of coitus to put down a movement or an expression,” he was quoted saying.

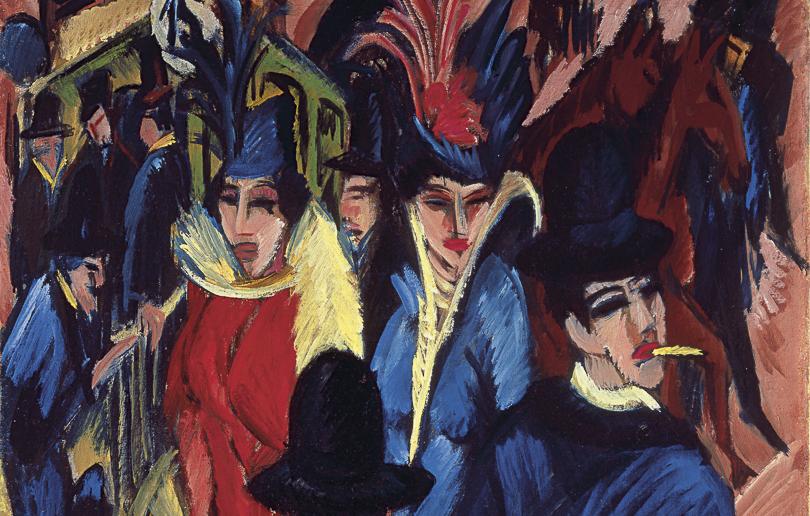

His most renowned painting, is, perhaps, the 1913 Streets of Berlin, which embodies the dynamism of the new city both through frantic brushstrokes and through the scene that unfolds: it looks like a snippet from the life of the bourgeoisie, but the flamboyantly-clad women, complete with large hats and statement coats, are actually high-class prostitutes, staring at a shop window. Fashion plates served as inspiration.

“Consumer culture was dominant, giving rise to department stores, flashy advertising, and rampant prostitution,” explained the two curators. “As such, and as a conveyer of modern life, he faithfully studied these developments and perused storefront windows, fashion journals, and walked the streets themselves like a flâneur so that he could accurately portray life in Berlin.”