These letters had been preserved by the descendants of painter Henry Cooke White, a longtime friend of Williams. What Kahn found in the correspondence and mentions in newspapers and archives is chronicled in the new book Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857-1907 published by Wesleyan University Press. The book features her surviving works, many published for the first time, ranging from a moody 1892 watercolor of sailboats in Maine to a pensive 1895 portrait of her landlady.

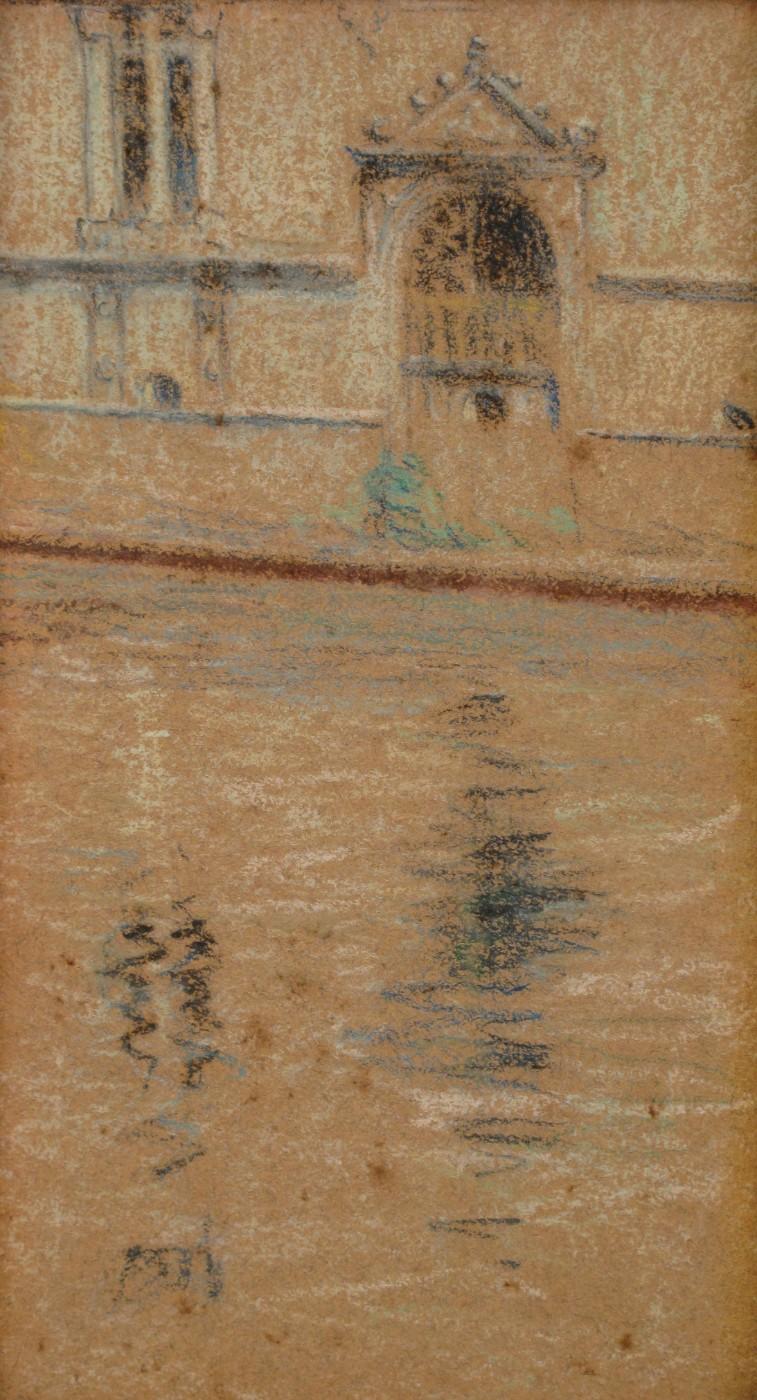

Mary Rogers Williams, Grand Canal, c. 1894. Pastel. Private collection.

When historian and journalist Eve Kahn encountered a trove of letters from artist Mary Rogers Williams in 2012, there were scarce references to the late painter online, and her work had barely been exhibited over the past decades. Yet in those letters was a rich insight into the life of an artist who dedicated herself to capturing the world she witnessed, from her home in New England to vistas from her extensive European travels, in a distinctive Impressionist style.

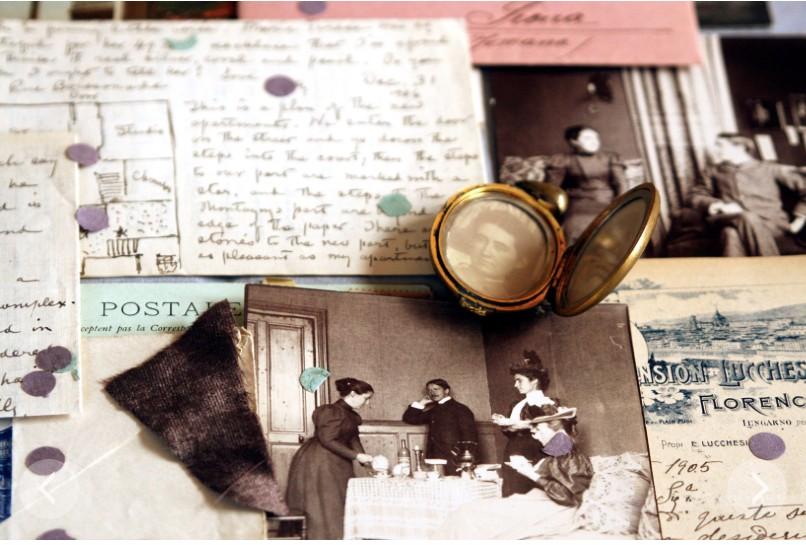

Mary Rogers Williams’ importance is partly due to quantities of surviving correspondence and ephemera: dried flowers from her travels, scraps of her dresses, confetti from Paris parades. In a family locket, Mary’s photo is in the left compartment. Private collection.

Mary Rogers Williams, A Profile, c. 1895. Oil on canvas. Shown at the New York Water Color Club and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1895. Private collection.

“The family owns not only perhaps 100 of her 120 known surviving paintings and pastels but also thousands of pages of her astonishingly vivid letters,” Kahn said. “For hardly any other 19th-century artists, men or women, do we know what they were thinking, wearing, eating, reading, wondering about, critiquing in the art world, and trying to capture with paints or pastels, on a particular day.”

One of those pastels—a portrait of White—was exhibited in a 2009 survey of White’s pastels at the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Aside from that, her art had been seldom seen by the public in a century. “No one in her family or social circles quite knew how to perpetuate her legacy after her sudden death,” Kahn said. “And for a researcher, her name is maddeningly ordinary.”

Records of Williams in art historical texts are fleeting. Still, there is contemporary admiration of her work in newspapers and journals. The New York Sun admired the “hazy, silvery light and delicate sentiments” of her 1893 pastels exhibited at the New York Water Color Club; the Quarterly Illustrator in 1894 described her as “an artist with rare and poetic instinct and feeling.”

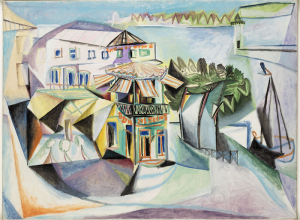

Mary Rogers Williams, Azay-le-Rideau near Tours, France, undated (probably 1902). Pastel. Private collection.

Despite her talent, she struggled to find time for her art. Born in 1857 to a baker in Connecticut, she did not have the advantage of wealth or ample free time. She studied with leading artists such as James McNeill Whistler and William Merritt Chase and explored anatomical drawing at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, but she also worked, running the art department at Smith College in Massachusetts from 1888 to 1906. An unconventional woman of her time, she never married, enjoyed bicycling, played golf, and dedicated every vacation and sabbatical she could to travel. She always wrote to her sisters about her adventures, describing how “Vesuvio was a dream against the early sky” and how in Norway waterfalls “sounded like wind in the pine trees.” Kahn retraced Williams’s steps in her research, finding the archways in Siena where she sketched and hiking to the ruins she studied in Florence.

Often dismissive of the mainstream trends in art, Williams favored a loose painting style with a dreamlike quality through abstracted buildings, tall horizons dotted with trees, and quiet portraits of women. As she wrote, she was “forever seeing new beauties” in these examinations of daily life and nature. Frequently these paintings were in the subdued palette used by turn-of-the-century Tonalists. They are a contrast to her sketched studies that captured in detail small moments including a priest dozing in a train car and the stripes on a tabby cat.

Mary Rogers Williams, Early Morning—Waterford (also called Aurore and Morning—Waterford), 1897. Pastel. Mary’s view of the Connecticut shoreline hamlet where her artist friend Henry Cooke White lived, and long preserved her artworks and archives. Eve M. Kahn collection.

Williams was not without success in her lifetime. She exhibited her landscapes and portraits at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the National Academy of Design, and the Paris Salon. Yet she found it hard to balance her teaching workload with her art, lamenting once to her friend White that “I get desperate about not having any time at all to paint.” Furthermore, she faced limitations as a woman on her independence and autonomy. (“I’ve been wishing ever since yesterday that I were a man,” she once wrote, “that I might have nerve and head enough to drive an auto—then I’d spend my last penny for one.”)

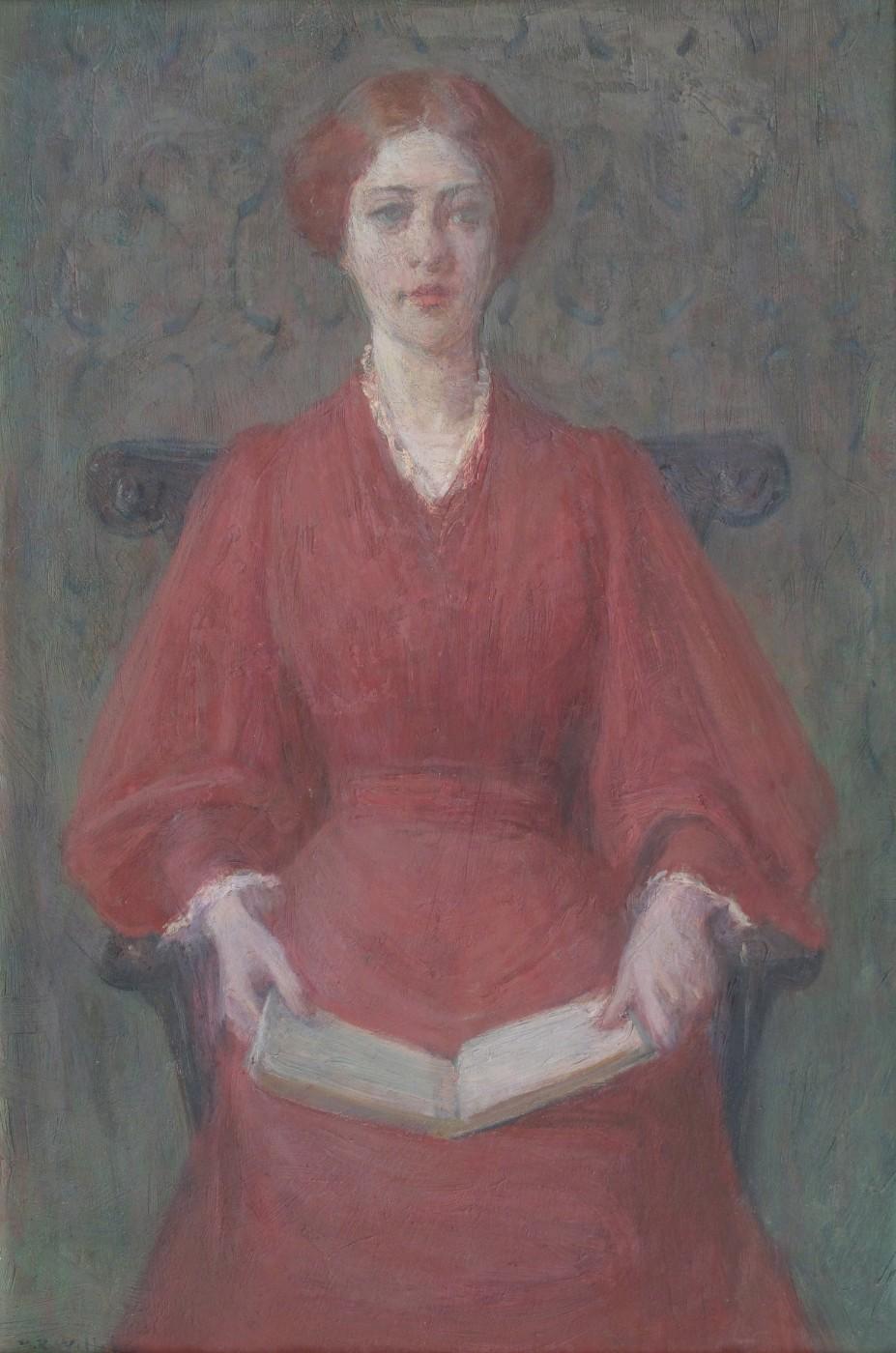

Mary Rogers Williams, A Girl in Red, undated (pre-1901). Oil on panel. Private collection.

When she died suddenly in Florence, she was buried under a marble cross in the Allori Cemetery, which is today rarely visited. Once in her letters, she joked that she was “writing a new epitaph now ‘Here lies one whose name was writ in pastel,’” a riff on the poet John Keats’s epitaph that evoked her frustration with the slow sales and attention to her art. Over a century following her death, that name is finally being elevated from its obscurity.

“I believe that work like mine—and there are a lot of historians on similar trails, look at what’s been done recently for Ida O’Keeffe, Agnes Pelton, and Hilma af Klint—can be inspiring to anyone who’s ever felt undervalued or unheard, or anyone who’s inherited material related to someone interesting but unknown,” Kahn said. “It helps to know that your story, too, is important.”