Throughout the nineteenth century, the rapidly developing technology of photography revolutionized popular media and its consumption. Once complicated, clunky, and expensive, by 1900, when Kodak introduced the popular and much more affordable Box Brownie camera, photography had become a part of everyday life, influencing how people saw themselves and the world, literally and figuratively. But just before the invention of the Brownie camera, in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the cabinet card was ubiquitous.

Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography, was on view at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art through November 1, 2020. It delved into the rise and fall of this popular form, and how it was a precursor to our current media-saturated moment.

W. A. Wilcoxon, Bonaparte, IA, [Baby], 1890s. Collodion silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2019.11

A collection of cabinet cards may have mirrored our Instagram feeds todays: idealized portraits, images of celebrities, cute pictures of babies and pets, and the occasional ad.

Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography was accompanied by a 232-page catalogue copublished with the University of California Press, Berkeley.

Unknown photographer, [Two girls], 1864. Albumen silver print (carte de visite). Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P1976.45.24

Before cabinet cards became popular, the carte de visit was commonplace. The dimensions of a calling card, these pocket-sized photographs were eclipsed by cabinet cards in the 1870s, which three times larger, measuring 6 1/2 by 4 1/4 inches, roughly the size of today's smartphones.

Charles L. Griffin, Scranton, PA, [Toddler with dog], c. 1892 Gelatin silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2016.106

This larger format allowed for greater detail, making portraits more accurate and engaging. The cabinet card could be displayed on its own in the Victorian parlor, where photograph albums were a fixture.

Unknown photographer, [Painter], 1890s. Albumen silver print. William L. Schaeffer Collection.

A more detailed image also lent itself to the possibility of a narrative element, as sitters were able to share more about themselves than just their likenesses.

M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT, [Getting the saw], 1880s. Albumen silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2016.104.A

Soon the cabinet card was used purely for entertainment, toying with the deceptive possibilities of the medium to amuse and amaze.

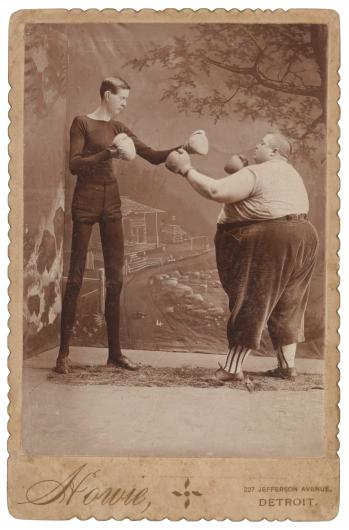

Howie, Detroit, MI, George Moore and Fred Howe, 1890s. Collodion silver print. Robert E. Jackson Collection.

This led to the introduction of a wide array of props, sets, and costumes, and gave performers an easily accessible platform to market themselves.

Napoleon Sarony, New York, NY, [Fanny Davenport], ca. 1870. Albumen silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2016.138

Napoleon Sarony, a leading photographer of the day, specialized in celebrity portraits. The new format of the cabinet card allowed him to show such stars as Thomas Moran, Mark Twain, Nikola Tesla, and Sarah Bernhardt in a more relaxed, casual way, that made them more approachable to their fans.

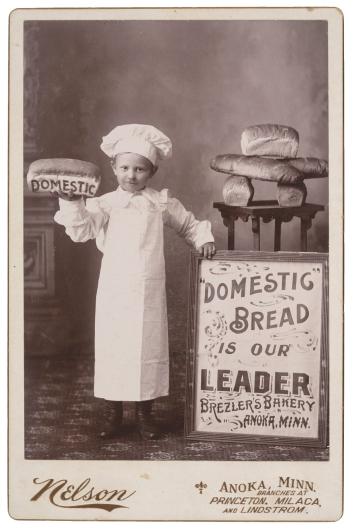

F. J. Nelson, Anoka, MN, Domestic Bread, c. 1890s. Collodion silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2017.50

The same versatility that attracted the average consumer also appealed to advertisers, who could market their products through good humor and accurate images of their products.

Benjamin J. Falk, New York, NY, Helena Luy, 1880s. Albumen silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2016.120

According to John Rohrbach, the Carter’s senior curator of photographs, “In our current moment of ‘selfie’ culture and social media-centered interaction, understanding the history of self-presentation and portraiture is more prescient than ever. This exhibition [revealed] how nineteenth-century Americans approached photography far more playfully than ever before, a transformation that forever shifted our relationship to the medium.”

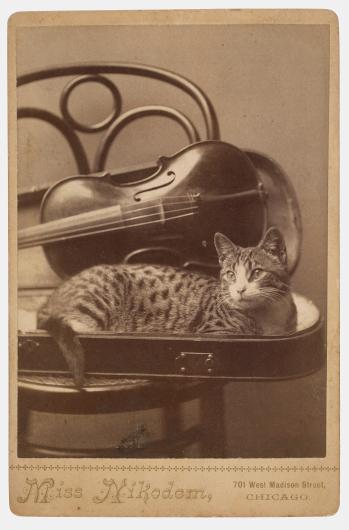

A. M. Nikodem, Chicago, IL, [Cat], 1880s. Albumen silver print. Robert E. Jackson Collection

Just like today, Victorians wanted to capture simple moments of beauty in everyday life, and the likeness of their cherished companions.

W. A. Wilcoxon, Bonaparte, IA, [Baby], 1890s. Collodion silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2019.11

A collection of cabinet cards may have mirrored our Instagram feeds todays: idealized portraits, images of celebrities, cute pictures of babies and pets, and the occasional ad.

Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography was accompanied by a 232-page catalogue copublished with the University of California Press, Berkeley.

Unknown photographer, [Two girls], 1864. Albumen silver print (carte de visite). Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P1976.45.24

Before cabinet cards became popular, the carte de visit was commonplace. The dimensions of a calling card, these pocket-sized photographs were eclipsed by cabinet cards in the 1870s, which three times larger, measuring 6 1/2 by 4 1/4 inches, roughly the size of today's smartphones.

Chandra Noyes

Chandra Noyes is the former Managing Editor for Art & Object.