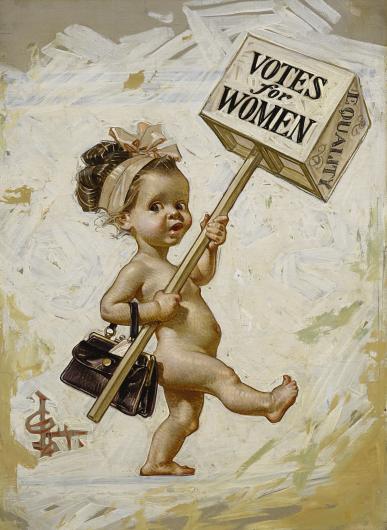

J.C. Leyendecker, detail of Votes for Women, Study for Saturday Evening Post Cover, January 1911. Oil on canvas.

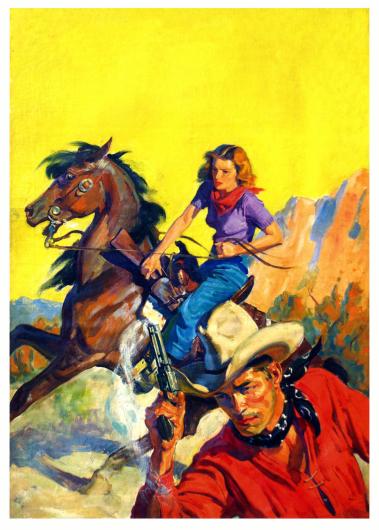

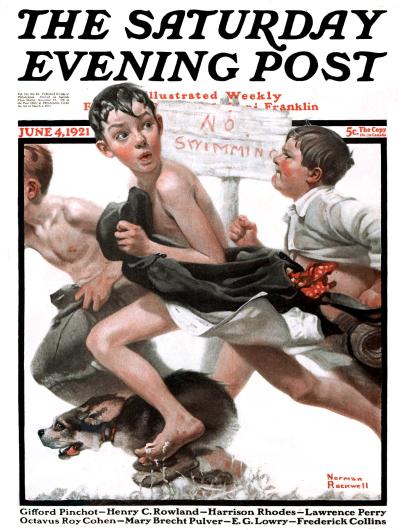

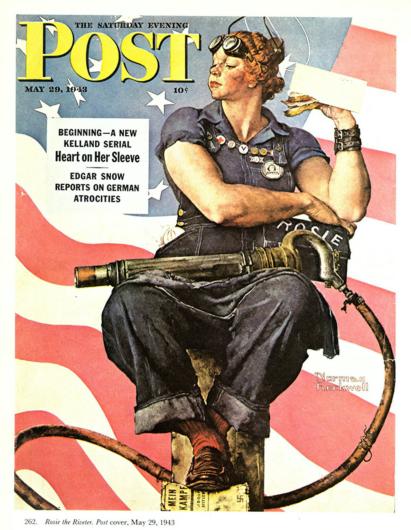

Though in many ways illustrated magazine covers are a thing of the past—the beginning of the last century to be precise—many of these long-gone artists are experiencing a resurgence in popularity as young people find and share their work online. And of course, many magazines still run illustrated covers—either regularly, as is the case with The New Yorker, or on special occasions, take the Harper's Bazaar annual Bazaar Art supplement.

Still, the internet age has made full-color imagery overwhelmingly accessible. This is to such an extent that it can be difficult to remember that, at the time these featured illustrations were created, today's accessibility to color did not exist.

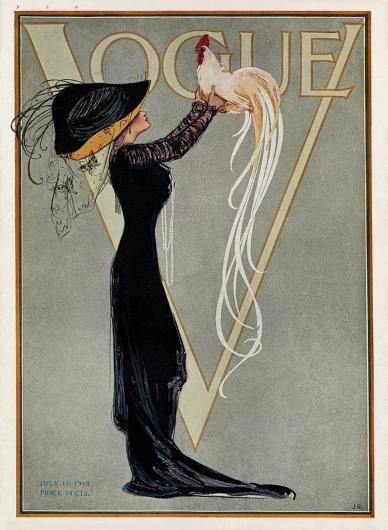

The earliest illustrators discussed here had limited color pallets—often grayscale and perhaps one other color—usually red, though sometimes green or orange. As technology and budgets evolved, full-color print runs became possible. Even then, these radiant magazine covers would often be the only full-color artwork individuals had regular access to. So, of course, they were highly desired and made with great care.