Esmaa Mohamoud, One of The Boys (White), 2019. Archival pigment print.

Basketball’s origins lie in white Canada and the U.S., where it was developed by Canadian physical education instructor, James Naismith, at a Massachusetts YMCA. Since the mid-twentieth century, the professional version of the sport has seen more diversity, while still being managed and financed by predominantly white, male-led industries. Though the following works differ in their media, common themes among them are the tensions between players, corporations, and spectators.

These artists all explore the thin lines between entertainment and dehumanization while also hinting at the hope and opportunity the game can offer. From community-minded installations, documentary photographs, confrontational mixed-media sculptures, to hyper-realist paintings, the following works force us to reconsider what basketball is on a local scale, who benefits, who is taken advantage of, and what fandom really means in the twenty-first century.

Esmaa Mohamoud, One of The Boys (White), 2019. Archival pigment print.

Mohamoud’s powerful work combines live performance, multimedia sculpture, textiles, and photography. One of the Boys is in part inspired by her own passion for basketball, but speaks to the many problematic associations we make between the sport, its players, and representation. Billowing gowns combine dramatic stitching and heavy draped fabrics with individual player jerseys. These compositions, born of the dresses themselves and the models who wear them, are full of juxtapositions: between gendered clothing and participation in sports, traditional “male” and “female” personas and self-presentations, celebrity and anonymity, as well as Blackness and whiteness and all the troubling cultural connotations each color has historically evoked.

Kevin Beasley, Harden, 2017. Polyurethane resin, wood, acoustic foam, NBA Jerseys. 87 x 66 x 5 in. (220.98 x 167.64 x 12.7 cm).

Artist Kevin Beasley’s process recalls assemblage in that he can only mold the materials he sources before they naturally solidify. For Harden, Beasley reassembled a collection of former Houston Rockets player James Harden’s jerseys, fusing them together with polyurethane resin on an acoustic foam base. In Beasley’s own words, this “mass of jerseys questions identity, aiming to re-establish the meaning of symbols and allowing the commodification and value of seasonal consumer goods to offer dual meanings within a renewed perspective.”

David Hammons, Higher Goals, 1986. Mixed media.

During his residency at the Cadman Plaza Public Art Fund in 1986, artist David Hammons produced Higher Goals out of telephone poles and basketball backboards, all of which were covered with thousands of bottle caps in geometric patterns. The temporary public installation stood between Brooklyn Heights and Dumbo from 1986 until 1987, where it seemed at first to tell a story both about the improbability of “going pro,” and about the many individual parts that contribute to a single game. Each bottle cap alluded to an aspiring basketball player, so few of whom are destined for a spot on the team. But Hammons’ work also spoke to the discipline the sport fosters, and urged viewers to aim much higher than the material confines of the piece.

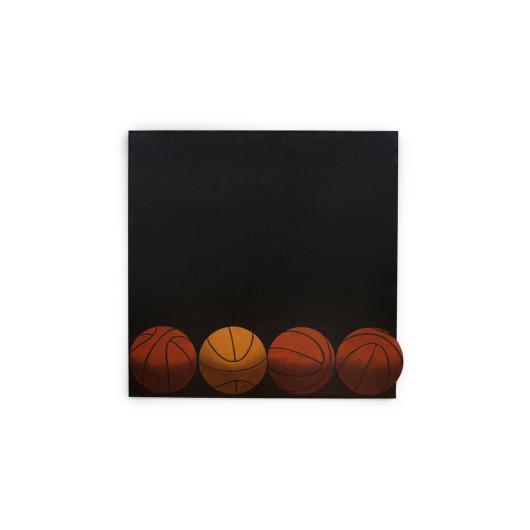

Barkley L. Hendricks, Formula 1, 1967-9.

Barkley Hendricks was an American photographer and painter known for his arresting portraits of Black sitters from around the world. In Formula 1, he presents four basketballs in a tight row at the bottom of a black canvas in his signature hyper-realist method of painting. The composition recalls how sporting equipment is stored between uses, but the ball on the far right has broken free of its confines. The canvas, as a result, has had to change shape to accommodate it. Hendricks has carefully indicated discrepancies in positioning and color among these objects, rendering them like animate sitters. The work reads startlingly like a series of portraits of individual athletes—dehumanized, shelved until needed, but obviously unique and sentient.

Walter Ioos, Jr., U.S. Women's Basketball Team, Pan-American Games, Caracas, Venezuela, from the series Shooting for the Gold, 1983. Dye transfer print.

In Ioos, Jr.’s photograph, we do not actually see a basketball. It seems to have been launched into our space, outside the frame, by player number 7. Her elegant movement is suspended in time; all the other players on the court await the ball’s landing point. Since 1960, Ioos, Jr. has created imagery for the biggest brands in sports apparel, major league sponsors, and for more than 300 covers of Sports Illustrated. He has also shown his work in fine art settings throughout the US, proving that arresting sports photojournalism need not be relegated to the commercial sector. His 1983 shot here encapsulates much about his body of work: it is a tense composition that makes clear the artistry in athleticism.

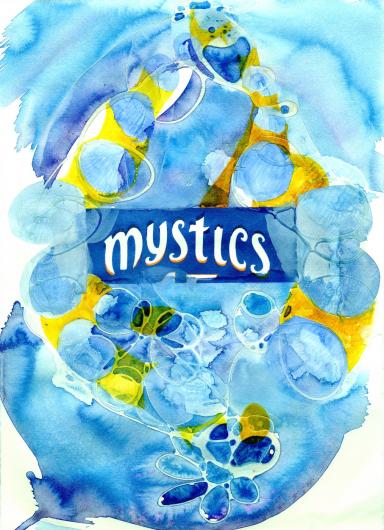

Suzanne McClelland, Team Play Her, 2004. Digital print, watercolor, and polymer on stationary.

In Suzanne McClelland’s 2004 series of digital prints, logos from WNBA teams are surrounded by swirling drips and washes of pale color. The works are startling, verging on uncomfortable, as they force a reevaluation of what these team names might mean when entirely removed from their commercial and athletic contexts. “Fire,” or “Mystics,” for example, when paired with Rorschach-like shapes, evoke bodily fluids and historical quasi-medical discourses that suppressed and dismissed women as inferior to men, especially in athletics. But other works that pair team names like “Sparks” and “Storm” with more vibrant hues seem celebratory, confrontational, and electric.

Janet Biggs, still from One-on-One, 2004. Two-channel video.

Biggs’s video focuses on former University of Connecticut basketball players Morgan Valley and Maria Conlon engaged in an aggressive, almost hypnotic drill. The subjects here were the NCAA 2004 National Champions, players who represented the results of obsessive dedication to their sport. Over the course of the continuous looping video, viewers see Conlon maintain control over the ball. But as viewers we are almost too close to these athletes. The installation thrust viewers into a dark, intimate setting, forcing us to confront how voyeuristic sports spectatorship can be. The specific, almost claustrophobic nature of the installation suggests the ownership fans often feel of winning teams and their players.

Theaster Gates, Ground rules. Free throw, 2015. Wooden flooring.

Gates’s work forces us to take a closer look at aspects of our environment we take for granted. Ground Rules, Free Throw is literally made of a southside Chicago gymnasium floor, its planks scrambled into the shape of a canvas. This material has spent several lifetimes being trodden and smoothed by basketball games and countless children learning to play. Stripped of its function, the tactile history of the wood is reimagined as an abstract, patterned composition. By refusing to let these spaces go unnoticed, Gates’s work seems an homage to the overlooked institutions that house our communities. It makes clear the beauty of the surfaces that help make the sport possible.

Brian Jungen, This Will Not Be Alright, 2016. Nike Air Jordans. 67 x 71 x 14.5 in. (170.2 x 180.3 x 36.8 cm).

Jungen is a Canadian artist of Dane-zaa First Nation and Swiss heritage. He is known for how he repurposes mass-produced items into forms associated with indigenous cultural objects and practices. Here, Jungen reconstructs Nike Air Jordan sneakers (one of the items with which he has worked for years), stripping them of their functionality. These shoes are often associated with the kind of prestige that allows someone to play basketball while wearing brand-name clothing. Here, the shoes form an amorphous structure, asking us to reconsider the material symbols that follow the sport. Without their ability to clothe a player, what do consumer goods actually add to gameplay and a player’s identity?

Esmaa Mohamoud, One of The Boys (White), 2019. Archival pigment print.

Mohamoud’s powerful work combines live performance, multimedia sculpture, textiles, and photography. One of the Boys is in part inspired by her own passion for basketball, but speaks to the many problematic associations we make between the sport, its players, and representation. Billowing gowns combine dramatic stitching and heavy draped fabrics with individual player jerseys. These compositions, born of the dresses themselves and the models who wear them, are full of juxtapositions: between gendered clothing and participation in sports, traditional “male” and “female” personas and self-presentations, celebrity and anonymity, as well as Blackness and whiteness and all the troubling cultural connotations each color has historically evoked.

Kevin Beasley, Harden, 2017. Polyurethane resin, wood, acoustic foam, NBA Jerseys. 87 x 66 x 5 in. (220.98 x 167.64 x 12.7 cm).

Artist Kevin Beasley’s process recalls assemblage in that he can only mold the materials he sources before they naturally solidify. For Harden, Beasley reassembled a collection of former Houston Rockets player James Harden’s jerseys, fusing them together with polyurethane resin on an acoustic foam base. In Beasley’s own words, this “mass of jerseys questions identity, aiming to re-establish the meaning of symbols and allowing the commodification and value of seasonal consumer goods to offer dual meanings within a renewed perspective.”

Rachel Ozerkevich

Rachel Ozerkevich holds a PhD in Art History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She's an art historian, writer, educator, and researcher currently based in eastern Washington State. Her areas of expertise lie in early illustrated magazines, sports subjects, interdisciplinary arts practices, contemporary indigenous art, and European and Canadian modernism.