Installation view of the exhibition "Women's Work" at the New-York Historical Society

The New-York Historical Society has always been passionate about spotlighting the lives and legacies of women in history through its Center for Women’s History, the first of its kind within a major museum.

The current exhibition, “Women’s Work,” which is on view through August 18, 2024, explores the history and evolution of women's labor in American society.

Through approximately 45 objects drawn from the New-York Historical’s museum and library collections, the exhibition attempts to define the phrase "women's work" by exploring the range of jobs that women have held over centuries, and the cultural norms related to those roles deemed appropriate for women. The show, which was curated by the curatorial staff and fellows of the Center for Women's History, proves that the work that women do (and have done throughout American history) is vitally important to all aspects of American life.

Inspired by the tactile objects that women have used or created, we selected five objects from the exhibition that show the history and development of women’s work.

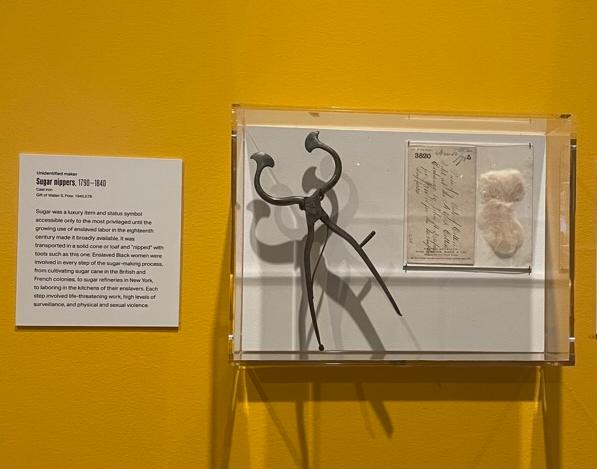

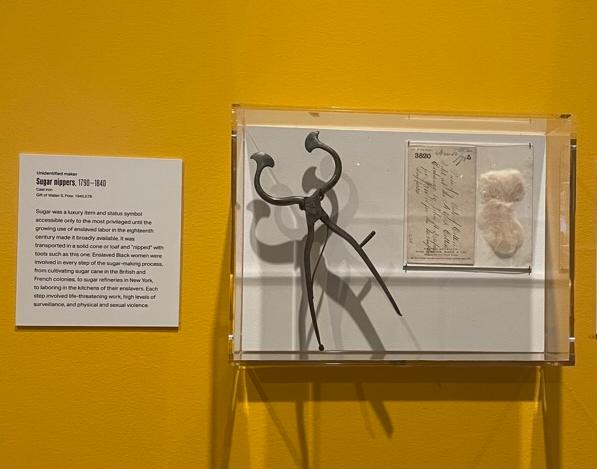

These cast iron sugar nippers were designed sometime between 1790 and 1840. Though the designer is unidentified, these were most likely created for enslaved Black women who worked in the sugar trade. Before the 18th century, when enslaved laborers worked in sugar cultivating, it was a symbol of high status, accessible only to the most privileged people. Black women were involved in every step of the sugar-making process, including its transportation, where sugar was put in a solid cone or loaf and “nipped” with tools such as the one on view. In addition, these women were responsible for cultivating sugar cane, refining sugar, and laboring in the kitchens of those who enslaved them.

Image: A pair of cast-iron sugar nippers.

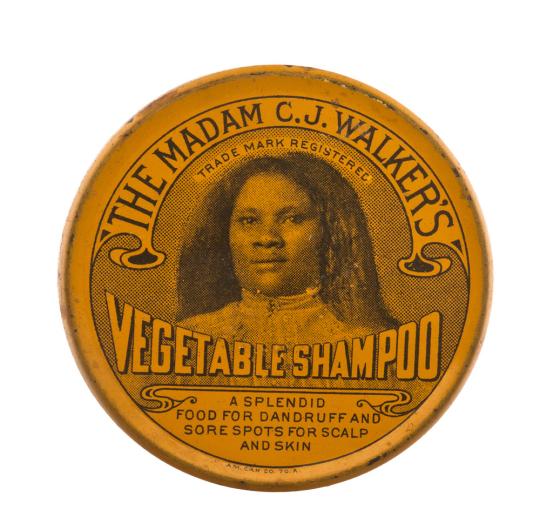

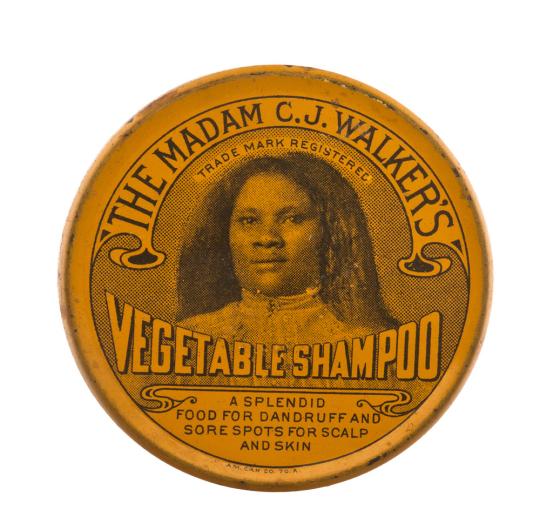

Madam C.J. Walker is known for being the first women to become a self-made millionaire. As a Black woman in the late 19th and early 20th century, Walker, who was based in St. Louis, was working for Annie Malone, an African-American hair-care entrepreneur. While working for Malone, Walker began to develop her own hair-care business with formulas specifically designed for Black women. Lacking access to traditional distribution networks, Walker promoted her products in independent Black newspapers and churches. As an advocate for Black women’s economic independence, she also trained thousands of other women as “Walker agents” to sell her products and earn commission. Walker used her fortune to fight Jim Crow and help African Americans achieve full citizenship, as well as to donate to many organizations. The NAACP has credited Walker for helping the organization survive during the Great Depression thanks to her generous donation.

Image: Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Co. Madame C. J. Walker’s Vegetable Shampoo, ca. 1910-20 Tin, paper New-York Historical Society, Gift of Lisa Kugelman in memory of Thomas P. Kugelman, 2015.36ab

In 1854, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in America to receive a medical degree. Her sister, Dr. Emily Blackwell, was the second. Their work to both offer women access to female doctors and to bring more women into the medical profession completely changed medicine in the United States. In the mid-nineteenth century, Dr.’s Emily and Elizabeth Blackwell opened a clinic called the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. On view is a medical kit owned by Dr. Grace Louise Merritt Vicario, a doctor who graduated from the clinic in 1892. This object represents Dr. Vicario's (and that of many other women) hard-won professional status as a physician.

Image: Medical kit owned by Dr. Grace Louise Merritt Vicario

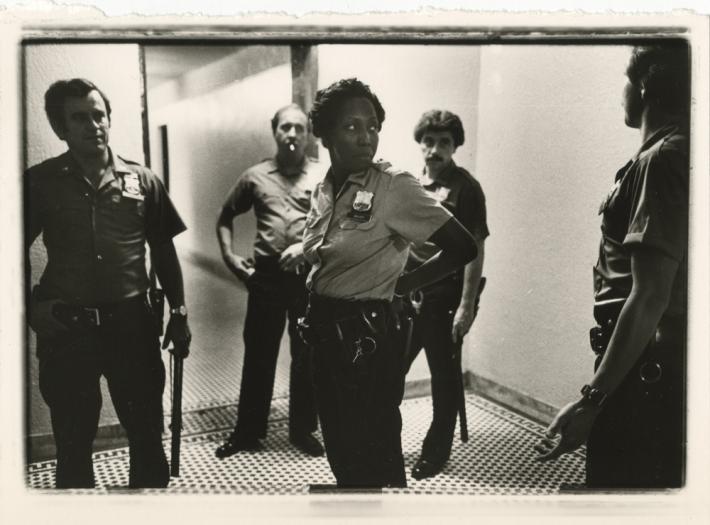

Today, women make up 16.8 percent of the over 324,000 police officers in the United States. In 2022, New York City elected its first woman Police Commissioner, Keechant Sewell. But women in carceral systems today can thank their predecessors in the 19th and 20th centuries. Women became part of the carceral system in 1854. New York was the first state to hire women: policemen’s widows were hired to clean cells and supervise female prisoners. These women, or “matrons” as they were called, were then asked to go undercover as investigators. They typically focused on abortion providers and lesbian and bisexual women. Despite these slow beginnings in law enforcement, these women paved the way for other women to be allowed to take civil-service exams and train in the use of firearms beginning in the 1930s, despite resistance. From there, a 1960s New York State court allowed women to seek high level promotions.

Image: Jane Hoffer (active ca 1975-present), photographer, Officer Walker, 1975 or 1978. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

Beth Levine (1914-2006) was an American fashion designer who became famous for her eclectic shoe designs. Levine started her career in fashion as a foot model for her size 4B foot. After marrying Herbert Levine in 1948, the pair launched their own shoe business. Beth Levine was just one of many women who played a significant role in the history of American shoemaking. Before the industrialization of shoemaking, the task of stitching shoes was relegated to American women for a few pennies per pair. When mass production became widespread, there became not only a demand for more streamlined processes of shoemaking, but also a demand for cheap shoes for the enslaved workers. By 1900, one-third of shoe factory laborers were women. Though their job of stitching and binding was complex, they were deemed “low-skill” workers, while machines with more specialized shoemaking processes were operated by men.

Image: a pair of shoes designed by Beth Levine.

These cast iron sugar nippers were designed sometime between 1790 and 1840. Though the designer is unidentified, these were most likely created for enslaved Black women who worked in the sugar trade. Before the 18th century, when enslaved laborers worked in sugar cultivating, it was a symbol of high status, accessible only to the most privileged people. Black women were involved in every step of the sugar-making process, including its transportation, where sugar was put in a solid cone or loaf and “nipped” with tools such as the one on view. In addition, these women were responsible for cultivating sugar cane, refining sugar, and laboring in the kitchens of those who enslaved them.

Image: A pair of cast-iron sugar nippers.

Madam C.J. Walker is known for being the first women to become a self-made millionaire. As a Black woman in the late 19th and early 20th century, Walker, who was based in St. Louis, was working for Annie Malone, an African-American hair-care entrepreneur. While working for Malone, Walker began to develop her own hair-care business with formulas specifically designed for Black women. Lacking access to traditional distribution networks, Walker promoted her products in independent Black newspapers and churches. As an advocate for Black women’s economic independence, she also trained thousands of other women as “Walker agents” to sell her products and earn commission. Walker used her fortune to fight Jim Crow and help African Americans achieve full citizenship, as well as to donate to many organizations. The NAACP has credited Walker for helping the organization survive during the Great Depression thanks to her generous donation.

Image: Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Co. Madame C. J. Walker’s Vegetable Shampoo, ca. 1910-20 Tin, paper New-York Historical Society, Gift of Lisa Kugelman in memory of Thomas P. Kugelman, 2015.36ab