Every December we share some of our favorite artworks throughout the year. These 11 artworks and objects kept our entire team engaged and excited about the art world, and the daily work of covering it for our dear readers in 2022.

The late We:wa demonstrated blanket loom weaving on the grounds of the United States National Museum while in D.C.

Perhaps the most famous nineteenth-century Indigenous Łamana or Two-Spirit historical figure, the late We:wa (various spellings exist) was a Zuni artisan, diplomat, spiritual leader, and humanitarian. They also played an integral role in the eventual recognition of Indigenous arts and crafts as fine art and were an incredible advocate of Indigenous rights in America. In this photograph, the late We:wa traveled to Washington D.C. to help anthropologist Matilda Coxe Stevenson's documentation of Indigenous culture, and to advocate for their people. They shared information about Zuni culture; did weaving demonstrations, including one outside the Whitehouse; posed for photographs; engaged American socialites; and even met President Grover Cleveland. During this trip and beyond, the late We:wa worked to educate colonial Americans, combatting stereotypes and advocating for Indigenous rights.

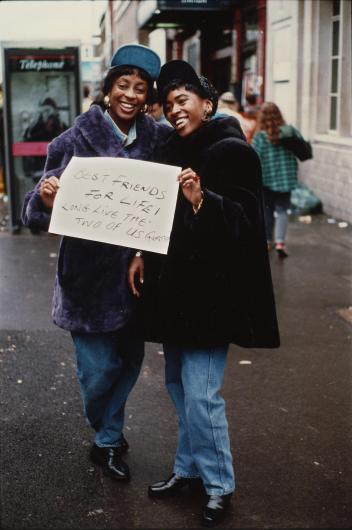

Gillian Wearing, Best Friends for Life! from Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say, 1992–93. Chromogenic print, mounted on aluminum, 17 1/2 x 11 3/4 in. (44.5 x 29.7 cm).

This artwork was covered in a story on the Gillian Wearing retrospective at the Guggenheim earlier this year. This work is part of her breakout series, Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say, in which she gave street photography a performative gloss by asking passersby to pose with placards written in their own hand that expressed their feelings at the moment.

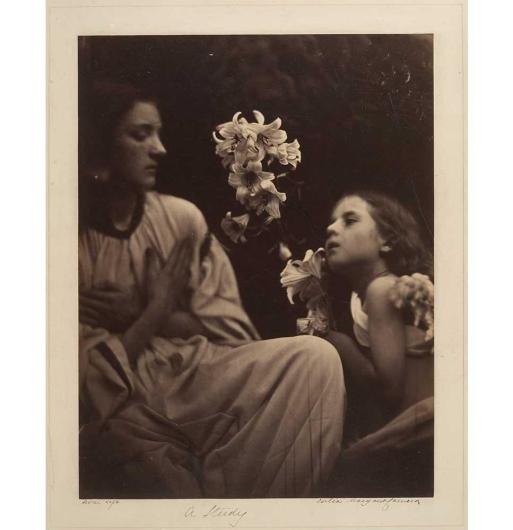

Julia Margaret Cameron, A Study, 1865-66.

Taken from a feature article on Julia Margaret Cameron, this artwork speaks to Cameron's photography style, where she would incorporate an out-of-focus style to blur boundaries in her portraits. In many ways, Cameron's work visualizes this blurring: it is caught between life and death, science and art, fine art and domesticity. And that is where beauty comes in.

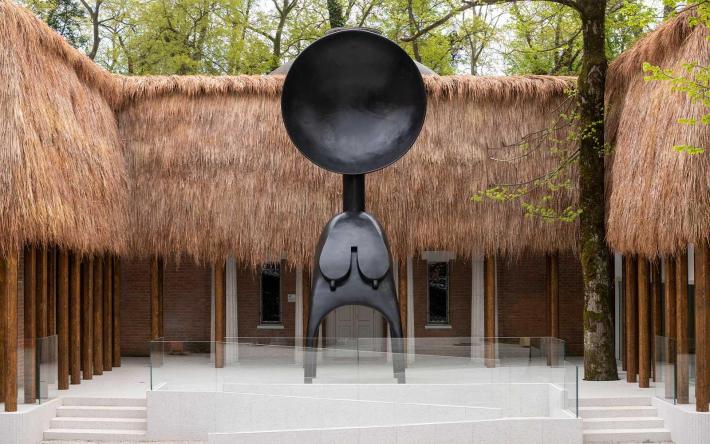

Simone Leigh: Facade, 2022.

Simone Leigh's pavilion at the Venice Biennale this year brought an unprecedented degree of Black female representation to the Biennale, and certainly exceeded expectations all around. This entryway to the Pavilion was meant to evoke a "1930s African Palace," through its transformation from a classic, Jeffersonian structure. It provides a powerful showcase that simultaneously obscures colonial past, while making the historical erasure of African cultural influence visible.

Frans Hal, The Laughing Cavalier, 1624. oil on canvas, The Wallace Collections.

This year saw a sizable amount of exhibitions and articles on lace and lace-making throughout art history. In the story, Handmade Lace & the Forgotten Women Behind the Trade, we learned about the art of lace-making before the mid-nineteenth century, and how tedious a task it came to be. Despite its status in the 15th and 16th centuries as a gendered, female-based hobby, lace was considered a gender-neutral adornment until the late 18th century. In this portrait by Frans Hal, a cavalier sits in a decadent collar of lace.

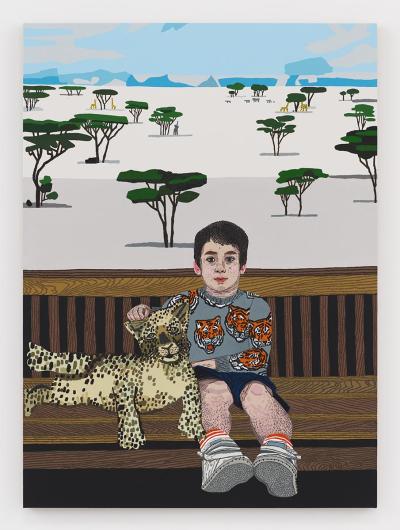

Jonas Wood, Kiki with Leopard, 2020. Oil and acrylic on linen. 52 x 38 inches (132.1 x 96.5 cm).

In February, we reviewed Jonas Wood's exhibition at David Kordansky gallery. In these works, Wood combines family members with images sourced from the internet. In this wonderful work, Kiki with Leopard, Wood portrays a folksy child seated with a contented feline on a bench. Behind them is an African plain littered with Acacia trees.

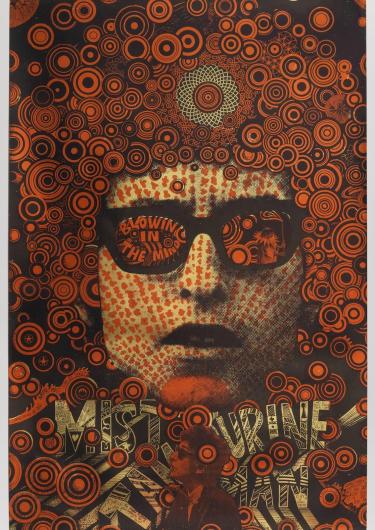

Martin Sharp, Blowing in the Mind/Mister Tambourine Man, 1968. Lithograph on wove paper.

In our review of the Drawing Center's exhibition, The Clamor of Ornament: Exchange, Power, and Joy from the Fifteenth Century to the Present, we highlighted the exhibit's design complete with saturated color walls and Chippendale-style wall text. Martin Sharp is known as a mastermind behind posters and album covers for some of the biggest names in '60s rock and roll history. This poster was placed adjacent to an Albrecht Dürer print of an interlaced roundel. The formal similarities are uncanny, with reverberating circle patterns giving us two very similar representations of mystical spiral affirmations, disseminated in the popular mediums of posters and prints over 500 years apart.

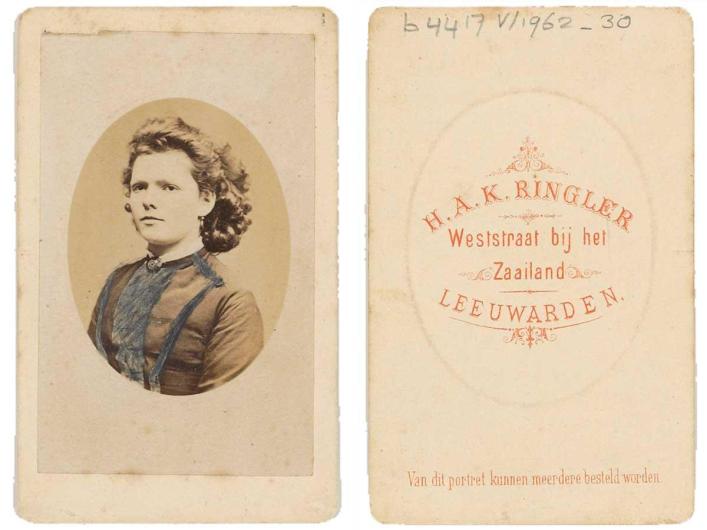

Elisabeth van Gogh, 1874-75, by H.A.K. Ringler Leeuwarden

In honor of a new book, The Van Gogh Sisters, by Van Gogh scholar Willem-Jan Verlinden, Art & Object looked into the long overlooked sisters of Vincent van Gogh – Anna, Elisabeth, and Willemien van Gogh. All three of his sisters led important lives, shaping Vincent's worldview and acting as important correspondents and, like all siblings, sources of tension for the artist.

John Everett Millais, Joan of Arc, 1865. Oil on canvas 32.2 x 24.4 in. (82 x 62 cm).

It is said that courage lies on the other side of fear. Deeply intertwined, fear and courage have traveled together across the centuries through the eyes and hands of artists. For many in the medieval period, courage was associated with heroism and war, frequently expressed through depictions of armor and weapons. John Everett Millais interpreted the bravery of Joan of Arc wearing armor and a red robe. Knelt in prayer with her eyes turned upwards and her hands clenched on a sword, Joan appears to be mustering the courage to go to battle.

Elizabeth I by Quentin Metsys the Younger (1583)

In our review of the Met's exhibition, Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England, we explored the Tudor's artistic influence on English cultural heritage. The exhibition, which featured over 100 objects created a picture of the thriving world inhabited by the international group of artists and craftsmen supported by Tudor patronage. No fewer than twelve works in various media feature the image of Queen Elizabeth I, the longest reigning and last of the Tudor monarchs. In this striking portrait, the Queen is depicted as a Vestal Virgin, an image of chastity that she cultivated throughout her childless reign. Her flawless white skin, framed by the delicate lace ruff is in stark contrast to the black, probably velvet, gown, making for a dramatic showstopper.

In 1944, a young Gordon Parks photographed workers at Penola, Inc. grease plant in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. During a time when industrial hubs during WWII rapidly manufactured the materials to support the Allied military effort overseas, the largely invisible labor included a diverse workforce that was left in the shadows. In Parks' images, there is a clear concern with telling the story of these workers, the harsh conditions they endured, and recognizing their individuality. The images Parks made of the Penola Grease Plant speak to the importance of helping individual experiences be visible and heard, particularly for people who had few public advocates, something which endured throughout the rest of his career.

The late We:wa demonstrated blanket loom weaving on the grounds of the United States National Museum while in D.C.

Perhaps the most famous nineteenth-century Indigenous Łamana or Two-Spirit historical figure, the late We:wa (various spellings exist) was a Zuni artisan, diplomat, spiritual leader, and humanitarian. They also played an integral role in the eventual recognition of Indigenous arts and crafts as fine art and were an incredible advocate of Indigenous rights in America. In this photograph, the late We:wa traveled to Washington D.C. to help anthropologist Matilda Coxe Stevenson's documentation of Indigenous culture, and to advocate for their people. They shared information about Zuni culture; did weaving demonstrations, including one outside the Whitehouse; posed for photographs; engaged American socialites; and even met President Grover Cleveland. During this trip and beyond, the late We:wa worked to educate colonial Americans, combatting stereotypes and advocating for Indigenous rights.

Gillian Wearing, Best Friends for Life! from Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say, 1992–93. Chromogenic print, mounted on aluminum, 17 1/2 x 11 3/4 in. (44.5 x 29.7 cm).

This artwork was covered in a story on the Gillian Wearing retrospective at the Guggenheim earlier this year. This work is part of her breakout series, Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say, in which she gave street photography a performative gloss by asking passersby to pose with placards written in their own hand that expressed their feelings at the moment.