Installation view of Benin Bronzes at the British Museum.

Who owns the past? This question has been asked for centuries and yet we still have no good answers.

Humans have been engaging in the looting, sale, and destruction of each other’s cultural objects for millennia. Look no further than the elite homes and gardens of Rome to see early precedents of this, littered as they were with statues, paintings, and other fine art objects taken from the conquered cities of Greece.

Although cultural thievery on a scale such as that practiced by the Romans does not occur as openly today, there is a dark underbelly to every museum and auction house that hides the tales of untold atrocities. And though many of these cases occurred decades, or even centuries, ago the repercussions of stolen cultural artifacts are still felt keenly within the modern nation state.

The Parthenon Marbles and Greece’s quest for their restitution is perhaps one of the most famous instances of such a thing, with the marbles now becoming a part of two different and diametrically opposed national identities. This list presents ten other such cases, some resolved, some not, of cultural objects of dubious legality, where they came from, where they are now, and who wants them.

Status: Unresolved. Where is it? Private Collections; Unknown.

Recent sales of Hopi and Navajo sacred objects in France have thrown into question not only the legality of selling potentially illicit items of cultural value, but have also shown the gross inequalities of representation and respect for indigenous peoples in the French law system.

In June of 2014, a sale at the Paris-based French auction house Eve was set to auction Hopi and Navajo sacred masks. The Holocaust Art Restitution Project (HARP) based in D.C. caught wind of the sale and sought a judicial proceeding in France to suspend the event as Hopi and Navajo representatives expressed concerns about the provenance of the items. The French Conseil des Ventes (Auction Houses Supervisory Board) refused the request. In doing so, they not only disregarded their own ethical code, which stipulates that they must exercise all due diligence in investigating and halting the sale of any cultural objects of supposed illicit status, but they also highlighted the gross inequity experienced by indigenous peoples in French legislature.

According to the Conseil des Ventes, the Hopi and Navajo (and subsequently any Native American tribe) had not legal capacities or standing to pursue cultural claims in France. Effectively, in one fell swoop, they declared that no indigenous peoples of Native North America have legal existence under French law, disregarding their recognized status within American law. This decision has also opened the field of private auctions within France to become a safe haven for the illicit sale of indigenous cultural artifacts.

The sale of the masks in question did take place in 2014, as have countless other succeeding sales of Hopi and Navajo cultural objects of sacred value. The tribe has successfully purchased back some items but many others have moved on to private collections or museums.

Status: Unresolved. Where is it? The Pushkin Museum, majority (Moscow, Russia); Istanbul Archaeological Museum, partial (Istanbul, Turkey).

Priam’s Treasure is a cache of gold and other valuables discovered by Heinrich Schliemann and Frank Calvert at the site of Hissarlik (Troy) in modern-day Turkey between 1871-1879.

Believing he had discovered Homer’s Troy, Schliemann conducted extensive excavations of dubious quality at the site in search of finds to support his claims, destroying much information in the process. Schliemann did not seek the proper authorization from the Ottoman government to remove the gold but, with the classic audacity of a nineteenth-century antiquarian, he did it anyway. The authorities discovered the removal of the objects as Schliemann was known to have his wife, Sophia, model the fine gold jewelry for the public.

The Ottoman government subsequently threatened to sue Schliemann and revoke his rights to dig at Hissarlik, but to no immediate effect. Eventually, Schliemann did return some of the treasure for permission to continue his work, however, the rest was acquired in 1881 by the Königliche Museen zu Berlin where it would remain until 1945. During the Battle in Berlin at the end of WWII, the treasure was secretly taken by the Soviet Army back to Russia at which time it was declared missing. It wasn’t until 1994 that the Pushkin Museum admitted to having the treasures. The museum had just opened an exhibit with them, claiming that, by Russian law, the treasures were war reparations against Germany and that they had no intention of returning the items either to Germany or Turkey.

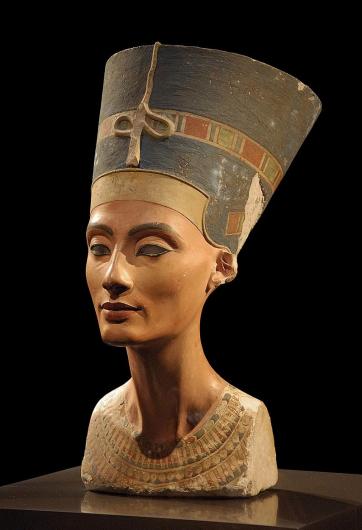

Status: Unresolved. Where is it? The Neues Museum (Berlin, Germany).

Thought to have been made around 1345 BCE, the Bust of Nefertiti is a painted limestone bust of the same-named Queen, wife to the pharaoh Akhenaten. The bust was discovered in a workshop in Amarna belonging to an artist named Thutmose in 1912 by the German Oriental Company, led at the time by Ludwig Borchardt.

While the Egyptian government and the GOC did conduct official meetings to discuss the division of finds between the two countries, it has been alleged that Borchardt grossly undervalued the bust to Egyptian officials with the intent of keeping it for export back to Germany. Supposedly, the photograph shown to the Egyptians was of very poor quality and when it came time to inspect the materials selected to go to Germany, Nefertiti was already wrapped up in a box. The bust has been in Germany since 1913 but was not displayed to the public until 1924, at Borchardt’s insistence.

It was at this first unveiling that the Egyptian government began its quest for repatriation of the Queen, a quest that is still ongoing today. The bust has also stirred up new controversies in the realm of ‘Digital Colonialism’ and the dissemination of knowledge from large, mainly western art institutions. The so-called ‘Nefertiti Hack’ is a part of a larger debate concerning the digitization of museum collections that, in some ways, threaten the traditional model of the modern museum. As such, many museums see this as an end-times scenario and have gate-kept much of their collections from an online presence with poor or no digitization of their records.

In the mid-2010s, the Neues Museum conducted 3D scans of much of its collection, Nefertiti included, but did not make the scans accessible to the public. Two artists in 2015, Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles, sought to rectify this and supposedly took their own scans of the bust in the museum with a concealed Microsoft Xbox 360 Kinect Sensor. In reality, they were most likely actually a part of a double-blind hack in which they gained access to the museum scans, but the results were the same when they disseminated the scans online.

COVID-19 further pushed many museums to make their collections accessible online but the process is still ongoing for the bust of Nefertiti as is Egypt’s bid for the objects return, last made in 2020.

Status: Resolution Forthcoming. Where is it? The Rubin Art Museum (New York, New York, USA).

These intricately carved wooden frieze panels date to fourteenth and seventeenth century CE religious complexes from modern-day Nepal.

The larger of the two once stood as a gateway for the Yampi Mahavihara temple complex in present-day Lalitpur. It entered the Rubin Museum in 2010 when it was purchased through a private sale. The other, depicting an Aspara, was taken from the Itum Bahal monastery of Kathmandu and was purchased by the Museum in 2003, also through a private sale.

It wasn’t until the Fall of 2021 that a nonprofit organization called Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign recognized the friezes and alerted the Rubin Museum about their illegal status. Through a successful social media campaign, the stolen nature of the friezes was verified, and the Rubin Museum has since pledged to return the items at their expense to the Department of Archaeology in Nepal. This exchange is expected to occur in May of this year.

Status: Possible Resolution. Where is it? The Victoria & Albert Museum (London, England).

In the Spring of 1868, British troops entered and looted the fortress of Maqdala in Ethiopia. They came away with many stolen sacred and secular artifacts which they intended to sell. Among those objects was the Maqdala crown, made sometime around 1740, an exquisite example of Ethiopian craftsmanship with embossed images of the Apostles and Evangelists.

After purchase, the crown was shipped back to England where, in 1872, it was placed in the South Kensington Museum (later to become the V&A). The crown has been displayed in the museum along with other precious objects of Ethiopian culture including a highly detailed nineteenth-century dress.

Recently, the V&A has offered to send some of these cultural objects back to Ethiopia on a long-term loan, however, this offer has sparked new debates about object ownership and whether items such as the Maqdala crown should be repatriated.

Some of these objects are of an incredibly delicate nature, such as those made of organic materials and many argue that institutions such as the V&A or the British Museum have the means to best preserve the materials. Other controversies such as those over the Parthenon Marbles have shown this argumentation to hold increasingly little weight as new, state-of-the-art museums continue to be built in the countries from which these materials were taken.

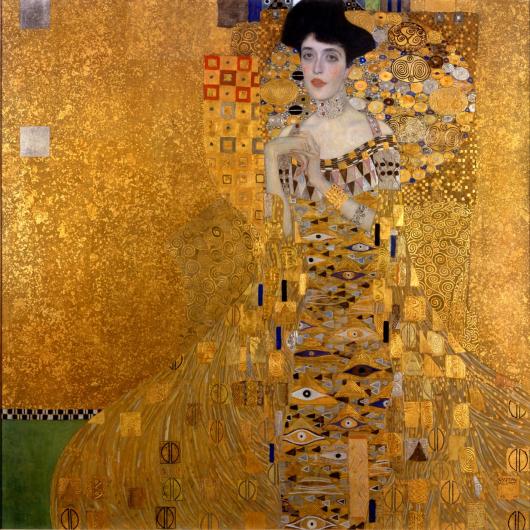

Status: Resolved. Where is it? Neue Galerie (New York, New York, USA).

Completed between 1903 and 1907, the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I belonged to the Bloch-Bauer family of Vienna up until WWII when it was seized by Nazi agents and eventually placed in the Galerie Belvedere. The painting was also renamed to Dame in Gold as a means to further alienate its Jewish owners and the painting’s subject. After the war in 1946, the Bloch-Bauer family sought the return of many artworks wrongfully seized but they did not receive any pieces by Klimt, of which there were multiple including Portrait of Adele.

The Galerie Belvedere based its rejection of the family’s claims on Adele’s will, drawn up in 1923, that stated she wished her portrait and a few other works to be left after her husband’s death to the Austrian State Gallery in Vienna.

In 1998, Maria Altmann, Adele’s niece by marriage, sought restitution again from the Austrian government. When the government once more denied her claims, Maria and her lawyer E. Randol Schoenberg took the case to the US Court system where they sued the Austrian Government and the Galerie Belvedere. Five paintings were returned to Maria Altmann in 2006. Portrait of Adele was sold by the family for a record $135 million. It now hangs in the Neue Galerie in New York City.

Status: Resolved. Where is it? Cerveteri (Italy).

The Euphronios Krater is a Greek terracotta handled bowl that was illegally excavated from an Etruscan tomb near the Italian settlement Cerveteri. Dating to around 515 BCE, the krater was made and painted in Athens and was originally used for mixing water and wine together during symposia (Greco-Roman dining parties) before its final deposition into a tomb.

Attributed to the painter Euphronios, the bowl features two Greek red-figure scenes: One depicts an episode from the mythic Trojan War and the other depicts sixth century BCE Athenian youths donning armor for battle. It is considered one of the best examples of Archaic Greek red-figure pottery. Historically, the vase is a crucial piece of evidence that showcases the strong economic and trading ties between Etruscan Italy and Ancient Greece.

Italian court records indicate that the krater was looted from Cerveteri in 1971 and then sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1972 for $1.2 million. The art dealer, Robert E. Hecht, an American living in Rome at the time, was accused of dealing in illicit antiquities before and after this sale. He denied all such claims.

One director at the Met, Thomas Hoving, noted that a Greek vase from an Etruscan tomb of such good quality could only have come from illegal circumstances. After years of investigation, it was finally determined that the krater was indeed looted and illegally sold.

In 2006, the Met and the Italian government reached a settlement for its return alongside other objects of illegal status and, in 2008, the Euphronios Krater finally returned to Italy with much fanfare. It now sits on display in the Cerveteri Museum.

Status: Unknown. Where is it? Unknown.

After the 2003 American invasion of Iraq, the ensuing collapse of the Iraqi government led to the violent looting of the Iraq Museum in Baghdad. The items taken, or even destroyed, are priceless not only for their antiquity and material quality but also because they are representative of one of humanity’s oldest civilizations.

Many of the pieces stolen date to between 2,000-3,000 years old and are of extremely high quality. The Gold of Nimrud, for example, is a collection of over 1,000 pieces of exquisitely crafted jewelry and precious stones. Most of the Nimrud gold and other objects have been recovered over time, however, many pieces are still missing.

This ivory plaque depicting a lioness attacking a Nubian is one such piece. Inlaid with lapis lazuli and carnelian, and overlaid with gold, this plaque dates to the eighth century BCE and was one of the Museum's most iconic pieces.

Status: Mixed Results. Where is it? The British Museum, partial (London, England); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, partial (New York, New York, USA).

The Benin Bronzes are a grouping of several thousand metal plaques and sculptures looted from the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin (Nigeria) by British forces in 1897. Many of the bronzes date to the thirteenth century CE and were made using the lost-wax casting method.

In 1897, a British expedition sought to enter Benin City supposedly with the secret intent of dismantling the monarchy at the time. City officials told the incoming British to delay their arrival since they would not be allowed entry while rituals were being performed. The British did not heed this request and continued their journey only to be ambushed by Benin warriors. Out of the 230 or so individuals from the British enclave, only two survived the encounter. A retaliatory naval expedition set out from London the following week which resulted in the sacking and destruction of Benin City.

Countless pieces of art were taken, including the bronzes, with the justification for the seizure being that they were ‘spoils of war.’ Today, only about fifty examples of Benin art exist in Nigeria. By contrast, over 2,400 pieces are held by American and European Museums. Since gaining independence in 1960, Nigeria has been requesting the return of the bronzes with mixed results.

While the majority of the bronzes in the British Museum (about 700 pieces) do not seem to be going anywhere, more promising signs from other institutions have peppered the news as of late. France approved the repatriation of twenty-six items in 2020, at least one bronze was returned from Scotland in 2021, and Germany has plans to return looted Benin items this year. The Smithsonian National Museum of African Art also announced in March that it would be returning thirty-nine bronzes to the National Museum of Benin.

Status: Unresolved. Where is it? Various Museums; Private Collectors; Unknown.

In November of 1986, a group of looters dug tunnels into Huaca Rajada, a Moche archaeological site in northern Peru dating to about 700-1 BCE. By February of the following year, the looters encountered Moche brick walls within their trench. When they punched through the bricks, a literal cascade of gold, silver, and other precious Moche objects poured out on top of them. Investigative work since then has concluded that the looters found an intact elite Moche tomb.

They left very little behind for archaeologists, however, taking whatever of value they could and destroying or damaging anything else in the process. One looter, interviewed in 2002, noted that hundreds of ceramics were caught in the crossfires of the looters rush to get the gold and precious objects out.

It seems that, thanks only to internal fighting amongst the looters, the police caught wind of these activities in time to intervene before more spoliation occurred. Even so, enough damage had already occurred and priceless Moche artifacts carted off, presumably to the art markets of varying legality. While some items looted from Sipán have been identified and recovered, such as a collection of fine gold jewelry seized from Sotheby’s in 1994, much of what was looted has yet to resurface.

Status: Unresolved. Where is it? Private Collections; Unknown.

Recent sales of Hopi and Navajo sacred objects in France have thrown into question not only the legality of selling potentially illicit items of cultural value, but have also shown the gross inequalities of representation and respect for indigenous peoples in the French law system.

In June of 2014, a sale at the Paris-based French auction house Eve was set to auction Hopi and Navajo sacred masks. The Holocaust Art Restitution Project (HARP) based in D.C. caught wind of the sale and sought a judicial proceeding in France to suspend the event as Hopi and Navajo representatives expressed concerns about the provenance of the items. The French Conseil des Ventes (Auction Houses Supervisory Board) refused the request. In doing so, they not only disregarded their own ethical code, which stipulates that they must exercise all due diligence in investigating and halting the sale of any cultural objects of supposed illicit status, but they also highlighted the gross inequity experienced by indigenous peoples in French legislature.

According to the Conseil des Ventes, the Hopi and Navajo (and subsequently any Native American tribe) had not legal capacities or standing to pursue cultural claims in France. Effectively, in one fell swoop, they declared that no indigenous peoples of Native North America have legal existence under French law, disregarding their recognized status within American law. This decision has also opened the field of private auctions within France to become a safe haven for the illicit sale of indigenous cultural artifacts.

The sale of the masks in question did take place in 2014, as have countless other succeeding sales of Hopi and Navajo cultural objects of sacred value. The tribe has successfully purchased back some items but many others have moved on to private collections or museums.

Status: Unresolved. Where is it? The Pushkin Museum, majority (Moscow, Russia); Istanbul Archaeological Museum, partial (Istanbul, Turkey).

Priam’s Treasure is a cache of gold and other valuables discovered by Heinrich Schliemann and Frank Calvert at the site of Hissarlik (Troy) in modern-day Turkey between 1871-1879.

Believing he had discovered Homer’s Troy, Schliemann conducted extensive excavations of dubious quality at the site in search of finds to support his claims, destroying much information in the process. Schliemann did not seek the proper authorization from the Ottoman government to remove the gold but, with the classic audacity of a nineteenth-century antiquarian, he did it anyway. The authorities discovered the removal of the objects as Schliemann was known to have his wife, Sophia, model the fine gold jewelry for the public.

The Ottoman government subsequently threatened to sue Schliemann and revoke his rights to dig at Hissarlik, but to no immediate effect. Eventually, Schliemann did return some of the treasure for permission to continue his work, however, the rest was acquired in 1881 by the Königliche Museen zu Berlin where it would remain until 1945. During the Battle in Berlin at the end of WWII, the treasure was secretly taken by the Soviet Army back to Russia at which time it was declared missing. It wasn’t until 1994 that the Pushkin Museum admitted to having the treasures. The museum had just opened an exhibit with them, claiming that, by Russian law, the treasures were war reparations against Germany and that they had no intention of returning the items either to Germany or Turkey.

Danielle Vander Horst

Dani is a freelance artist, writer, and archaeologist. Her research specialty focuses on religion in the Roman Northwest, but she has formal training more broadly in Roman art, architecture, materiality, and history. Her other interests lie in archaeological theory and public education/reception of the ancient world. She holds multiple degrees in Classical Archaeology from the University of Rochester, Cornell University, and Duke University.