In 1963 Oldenburg spent a short time in Los Angeles and began a new body of work, which would continue throughout the decade, called The Home. The works in this series include depictions of domestic and consumer objects, enlarged in scale, and often presented in “soft” and “hard” versions, with the “soft” sculptures sewn by Patty Mucha. He also created Autobodys, a performance about Los Angeles traffic. This drive-in performance made use of the spectator’s headlights to illuminate the choreographed movements of cars and bodies. In New York, he realized another car-themed work, Airflow, 1965, a series of soft sculptures depicting all the component parts of the 1935 Chrysler model. These were the first in a series of mechanically-themed soft sculptures that Oldenburg would render between 1965 and 1968, including a typewriter, giant fan, and drainpipe.

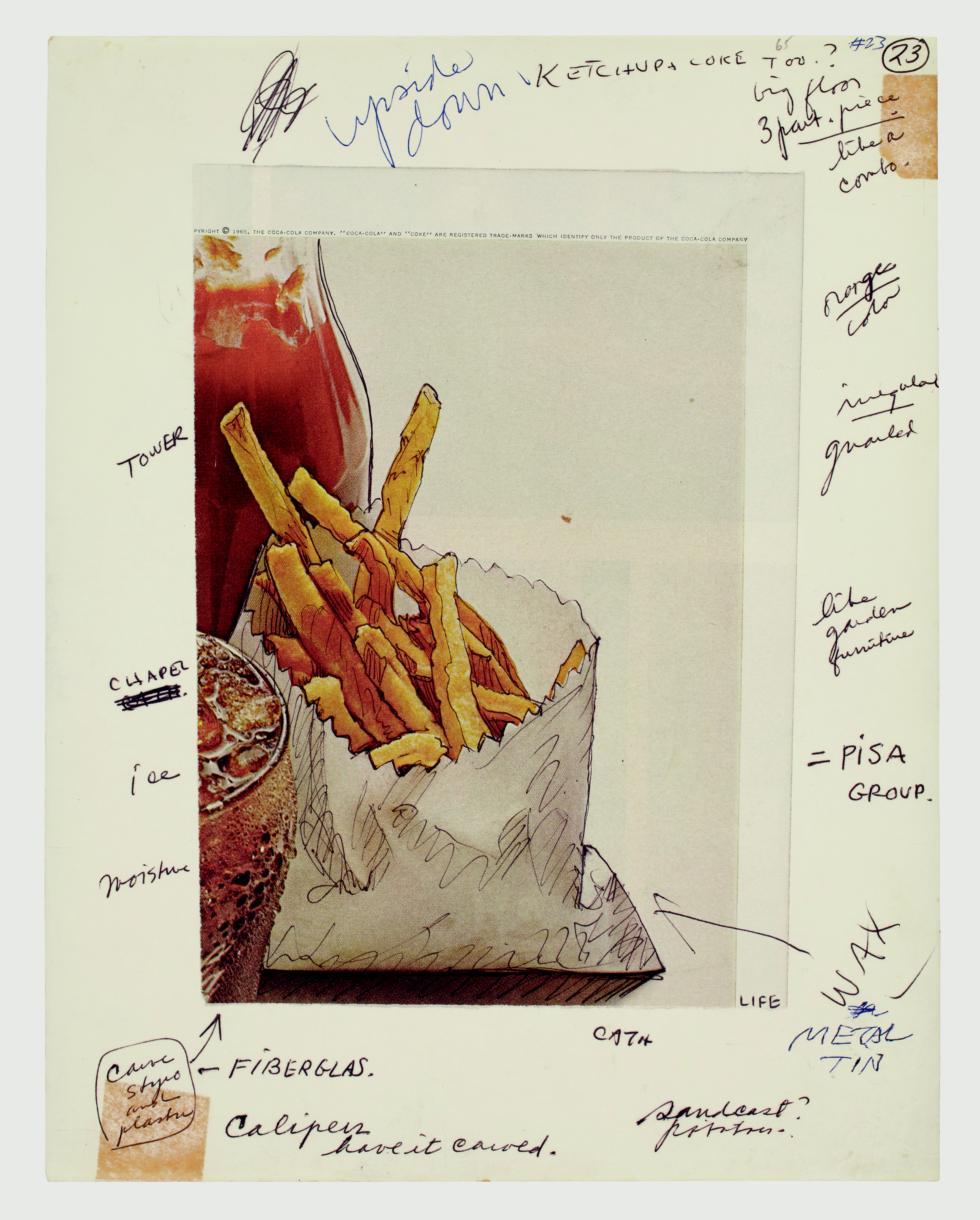

In 1965, Oldenburg began sketching a series of Proposed Colossal Monuments, public monuments that would transform sculptures of ordinary objects into geographical interventions on an architectural scale. These proposals included Wing-Nut for Stockholm in 1966, Floating Ball, 1967, for the Thames River in London in 1967, and Bat Spinning at the Speed of Light for Chicago in 1967.

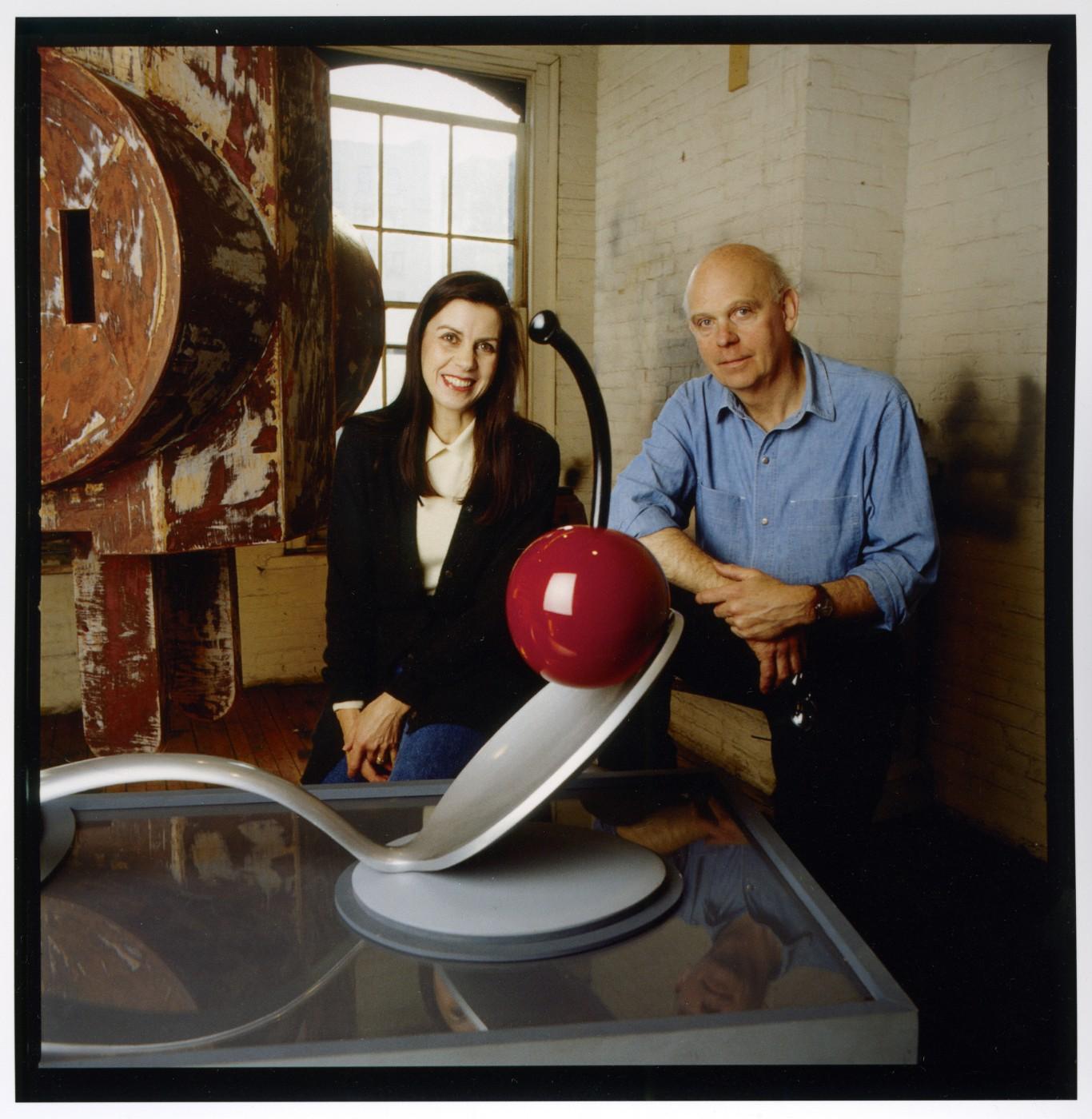

Among the early monuments Oldenburg realized was Trowel I, the first version of which was commissioned for the major international exhibition of contemporary art in Arnhem, the Netherlands, Sonsbeek 71. It was on the occasion of Oldenburg’s 1976 re-installation of Trowel I at the Kröller Müller Museum in Otterloo that he was reacquainted with Dutch art historian and curator Coosje van Bruggen, who advised him about the placement, design, and fabrication of the monumental work. She would become his formal collaborator that year, and his spouse in 1977, sharing credit with Oldenburg for their numerous subsequent large-scale public projects.

Van Bruggen was trained as an art historian at the Rijksuniversiteit in Groningen, and she worked as Assistant Curator for Painting and Sculpture at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam from 1967-71. She then taught art history at the Enschede Academy of Visual Arts. Throughout her artistic partnership with Oldenburg, van Bruggen also continued her independent work as a curator and art historian, serving on the curatorial team for Documenta 7 in 1982, and writing monographs on John Baldessari, Bruce Nauman, Hanne Darboven, and Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum Bilbao—projects which are documented in her individual archive.

Over the course of their more than three-decade-long collaboration, van Bruggen and Oldenburg designed and produced more than three dozen large-scale monuments in a variety of sites ranging from civic centers and museums to public parks. The Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen Archive contains extensive planning and logistical materials, correspondence, research, ephemera, and photographic and audiovisual documentation of these projects. Each commission entailed a lengthy process in which the artists would research the history of the site and broader context as well as the structural contingencies of a location before working out an idea and methods for construction. The exaggerated proportions of their monumental icons—billiard balls, a flashlight, shuttlecocks, a broom and dustpan, a torn notebook, and tumbling tacks among many others—heighten their inherent symbolism and particular resonances with their sites of installation. Transforming the built environments in which they are placed, Oldenburg and van Bruggen’s monuments of vernacular objects stand out in the discourse of postmodernism in architecture.

“The collaboration between Oldenburg and van Bruggen produced some of the most memorable sculptures of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, said Andrew Perchuk, deputy director of the GRI. “To acquire the records of their extraordinary partnership, as well as their individual archives, will provide foundational research material for generations to come.”

In the early 1980s, van Bruggen and Oldenburg embarked on a series of collaborations with architect Frank Gehry (whose archive the GRI acquired in 2018), including a theatrical production titled Il Corso del Coltello (The Course of the Knife), staged in the canals of Venice in 1985 with Oldenburg, van Bruggen, and Gehry as performers. For this project, Oldenburg and van Bruggen created Knife Ship, a monumentally-scaled prop in the shape of a Swiss Army knife. The artists also developed large-scale sculptures for two of Gehry’s architectural projects in Los Angeles. Toppling Ladder with Spilling Paint, 1987, was installed at Loyola Law School and Binoculars, 1991, is incorporated into Gehry’s building commissioned by the Chiat/Day advertising firm in Venice (now occupied by Google).

The couple continued to create large-scale public sculptures until van Bruggen’s death in 2009. Oldenburg continues to work and is currently finishing the production of Dropped Bouquet, a new sculpture edition. His most recent series, Shelf Life, 2017, consists of 15 works in which small sculptures and maquettes of Oldenburg’s’ key imagery—trowels, bowling pins, apple cores, etc.—are arranged on shelves, creating tableaus that reflect upon the history of Oldenburg’s and van Bruggen’s visual vocabulary and artistic output.

The Claes Oldenburg Archive, Coosje van Bruggen Archive, and Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen Archive will be catalogued and digitized by the Getty Research Institute and ultimately be made available to researchers.