On January 31, 2019 a symposium will take place in which the collaborative Tutankhamen project will be presented together with colleagues from the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities.

"Conservation and preservation is important for the future and for this heritage and this great civilization to live forever,” says Zahi Hawass, Egyptologist and former minister of State for Antiquities in Egypt, who also initiated the project with the GCI.

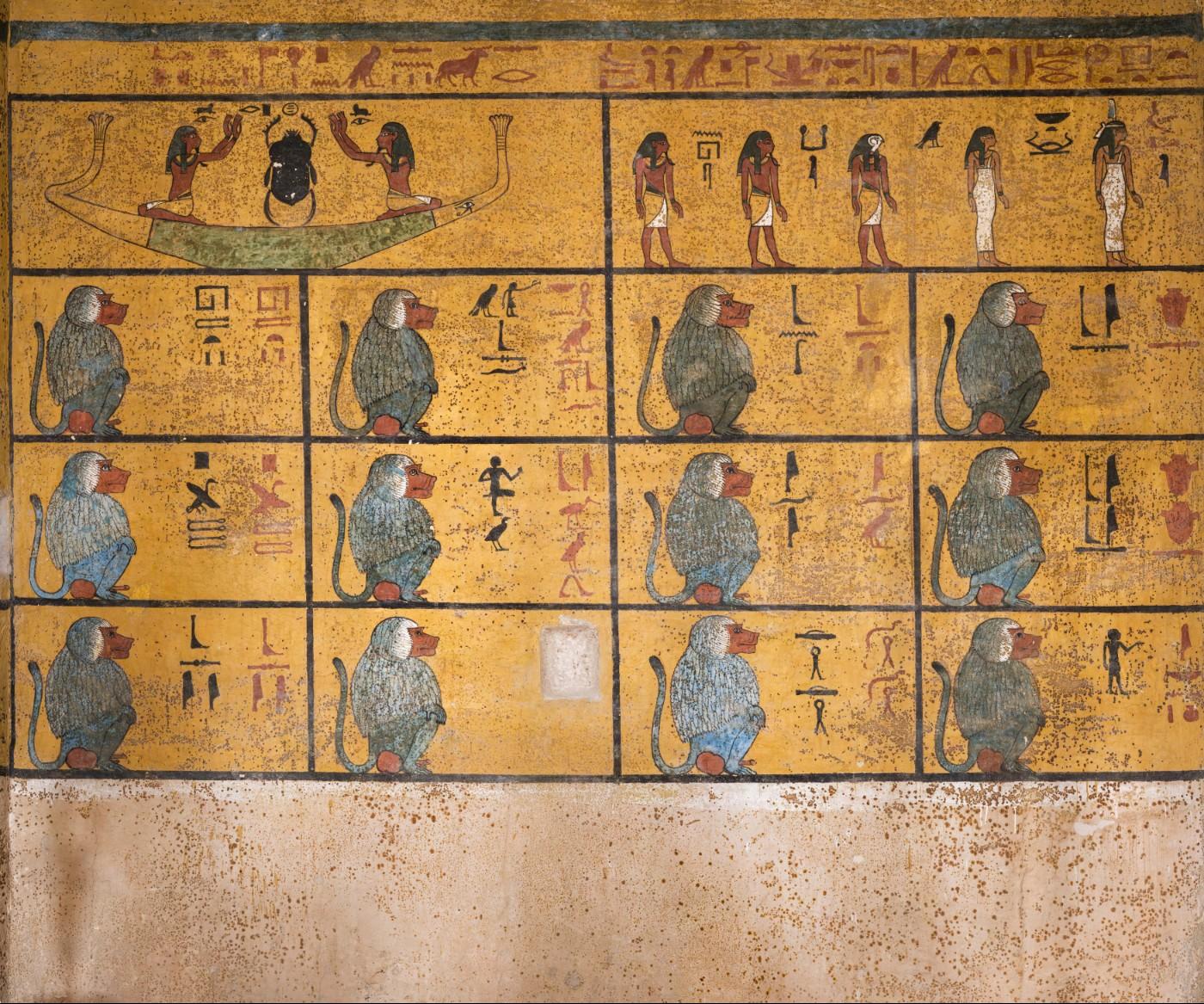

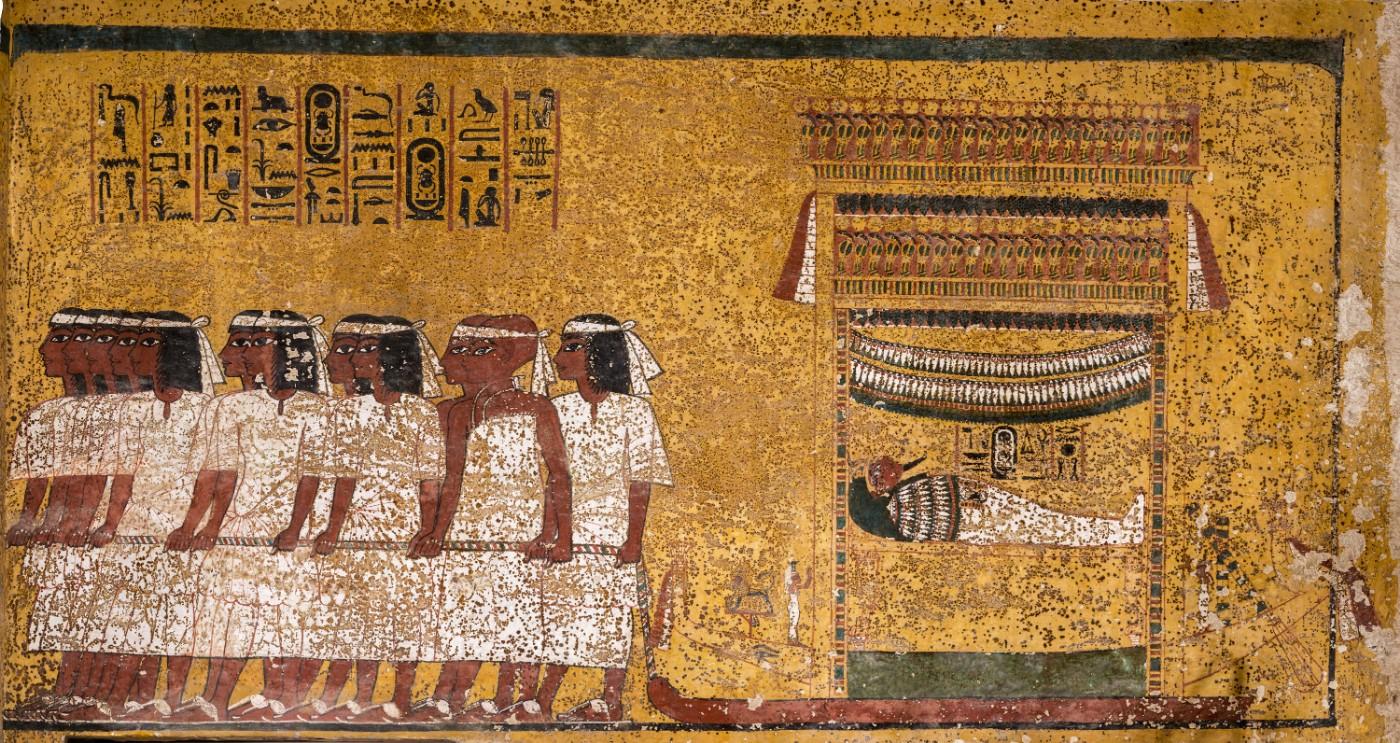

When the tomb was discovered in 1922 by archaeologist Howard Carter, under the patronage of Lord Carnarvon, the media frenzy that followed was unprecedented, and in many ways continues to this day. Carter and his team took 10 years to clear the tomb of its treasure because of the multitude of objects found within it. While the objects Carter’s team catalogued and stabilized were housed and secured, the tomb itself became a “must-see” attraction, open to the public and heavily visited by tourists from around the world. The tomb still houses a handful of original objects, including the mummy of Tutankhamen himself (on display in an oxygen-free case), the quartzite sarcophagus with its granite lid on the floor beside it, the gilded wooden outermost coffin, and the wall paintings of the burial chamber that depict Tut’s life and death.

The great demand for entry to the small tomb gave rise to concerns among Egyptian authorities about the condition of its wall paintings. Humidity and carbon dioxide generated by visitors promotes microbiological growth and can physically stress the wall paintings when the amount of water vapor in the air fluctuates. It was thought that brown spots—microbiological growths on the burial chamber’s painted walls—might be growing.