New Haven - The Yale University Art Gallery is pleased to present Artists in Exile: Expressions of Loss and Hope, a novel investigation of the experience of exile in the visual arts. The exhibition spans 200 years of art history and presents works by more than 40 exiled artists from nations across Europe, the Middle East, East and Southeast Asia, and the Americas. By juxtaposing exiles from different cultures and time periods, and highlighting a number of women artists, the exhibition expands on the narrative that consistently prevails in other publications and exhibitions-that of white, male artists who fled Europe during World War II. The show also reflects on and redefines the notion of exile, showing that it can be either a condition forced upon an individual—due to factors like genocide, war, or discrimination—or a chosen path, a means of separating oneself from surroundings that suffocate creativity. Much of the work created by these artists illustrates their trauma and a sense of loss; at the same time, it also shows innovations in form and technique, as artists adjusted to their new environments and experimented with different styles and means of expression.

Artists in Exile seeks to tell these stories of loss and hope, and to demonstrate the ways in which the experience of exile is universal. The exhibition is divided into four sections that trace various themes related to the exile experience: home and mobility, nostalgia, transfer and adjustment, and identity. These four themes bring together more than 100 diverse objects—including paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, and photography—and serve as entry points into the exile narratives of their makers. Drawn mainly from the Gallery’s encyclopedic collection, the exhibition is enriched by key works on loan from other institutions and private collections.

The section on home and mobility investigates how, for many people forced to depart their native or adopted country, there is no return to the known—only a departure for the unknown. “Home” ceases to exist as a physical space, and, as a result, exiles are compelled to create a sense of belonging in a new place, or to seek a renewed or continued connection to the one left behind. Artists such as An-My Lê, Ana Mendieta, and Abelardo Morell left their native countries at a young age and returned as adults, and their work reflects this reexamination of their lost culture and history. Mona Hatoum, on the other hand, transformed her exile into an opportunity to travel to different countries and collaborate with local craftspeople.

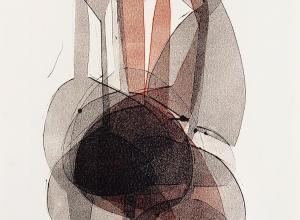

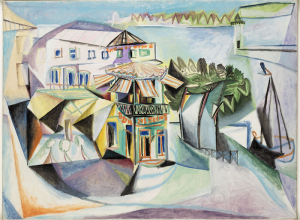

The theme of nostalgia illustrates the ways in which exiled artists engage with feelings of homesickness or longing by selecting subjects for their artwork that relate to their past. They also use these feelings as a springboard to test new techniques or refine old ones. Banished to Brussels for his political views, Jacques-Louis David sought to renew his former glory by painting portraits of other exiles who shared his beliefs, namely fellow supporters of Napoléon Bonaparte. After fleeing the Armenian genocide, Arshile Gorky combined Modernist influences, such as the work of Pablo Picasso, with motifs rooted in the Byzantine art of his native culture.

The dual theme of transfer and adjustment emphasizes how artists cut off from a familiar setting are required to acclimate to cultural differences while also accepting the loss of their former career, as they face a public with little or no knowledge of their established reputation elsewhere. Despite these challenges, they find ways to adjust, by applying their skills to local techniques and materials or by integrating different modes of expression into their work. For example, Matta, Kurt Seligmann, and Yves Tanguy transferred Surrealist ideas, such as automatism and imagery inspired by the subconscious mind, from Paris to their new American environment; they used these ideas to respond to the vast landscapes of the United States or to new scientific and technical achievements they witnessed.

The section on identity asserts how the experience of exile disrupts the evolution of an artist’s sense of self in many ways. Some exiles to the United States—including John Graham, George Grosz, and Jack Tworkov—initially tried to adopt a new “American” style or iconography in their work but eventually reverted to themes inspired by their upbringings as they felt progressively more alienated from American society. Others, notably Lucas Samaras, reacted to exile by turning to self-portraiture, out of a desire to overcome the emotional trauma of escaping a war-torn country. On the other hand, many women artists found that exile had a positive effect on their careers, giving them a chance to break free from societal boundaries and forge a new artistic identity. Living in Mexico, Elizabeth Catlett addressed themes of social justice in prints championing female laborers with whom she identified on a personal level, as the granddaughter of freed slaves. Iranian-born artist Shirin Neshat uses her exile in the United States as an opportunity to challenge stereotypes of Muslim women and explore wider issues relating to gender dynamics and freedom in Islamic societies.

“With war, genocide, and terrorism that still today cause waves of refugees and exiles, the paradigm of exile studies in the visual arts requires a new, more global approach,” states Frauke V. Josenhans, the Horace W. Goldsmith Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art and curator of the exhibition. “This exhibition portrays exile as a collective experience that pervades art history and has left its mark on centuries of artists and their work. Searching for common factors among such a diversity of works yields a reflection of a shared social and cultural history and, at the same time, reveals intensely personal stories of transformation.”

On View

September 1–December 31, 2017

Related Publication

Artists in Exile: Expressions of Loss and Hope

Frauke V. Josenhans

With essays by Marijeta Bozovic, Joseph Leo Koerner, and Megan R. Luke

This timely book offers a wide-ranging and beautifully illustrated study of exiled artists from the 19th century through the present day, with notable attention to individuals who have often been relegated to the margins of publications on exile in art history. The artworks featured here, including photography, paintings, drawings, prints, and sculpture, present an expanded view of the conditions of exile—forced or voluntary—as an agent for both trauma and ingenuity.

The introduction outlines the history and perception of exile in art over the last 200 years, and the book’s four sections explore its aesthetic impact through the themes of home and mobility, nostalgia, transfer and adjustment, and identity. Essays and catalogue entries in each section showcase diverse artists, including not only European ones—like Jacques-Louis David, Paul Gauguin, George Grosz, and Kurt Schwitters—but also female, African American, East Asian, Latin American, and Middle Eastern artists, such as Elizabeth Catlett, Harold Cousins, Mona Hatoum, Lotte Jacobi, An-My Lê, Matta, Ana Mendieta, Abelardo Morell, Mu Xin, and Shirin Neshat.