A two-step selection process involved a jury made up of community members and members of the City of Inglewood, where the Intuit Dome is located. “At first it was like, I need to persuade you that this is value added. Not everyone agreed with everything,” says Berson. “In general, it was a very positive experience.”

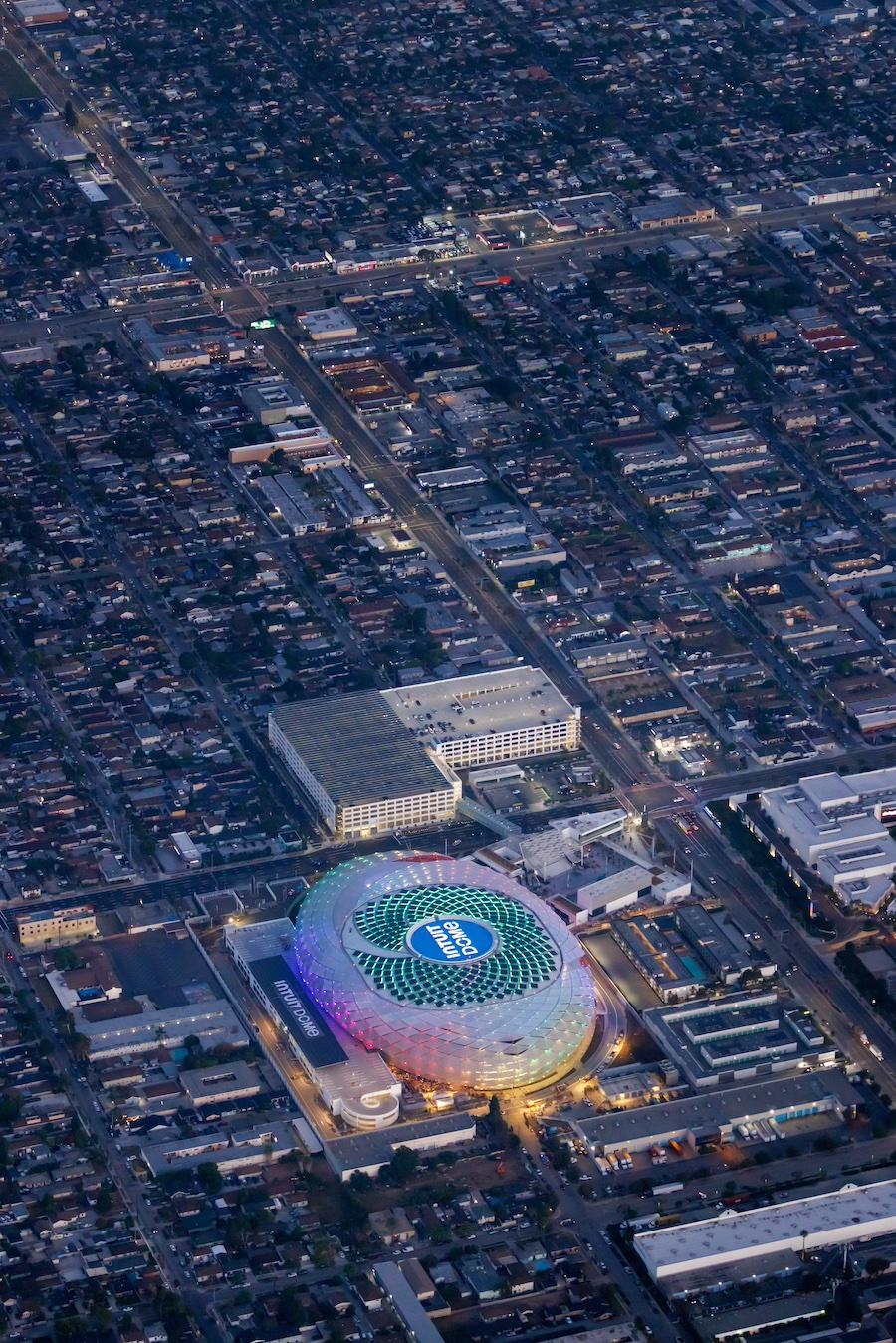

Jennifer Steinkamp, Swoosh, 2024. Lights built into the building skin, 950 x 630 x 150 ft.

When organizers were considering which Los Angeles artists to commission for the Intuit Dome— the new home of the Los Angeles Clippers— they could have chosen hometown names like Shepard Fairey, Betye Saar, or even Catherine Opie, whose photographs are currently on display there, on loan from MoCA. Instead, they chose artists from the community, people like Patrick Martinez, Michael Massenburg, Jennifer Steinkamp, Glenn Kaino, Charles Gaines, Refik Anadol, and Kyungmi Shin.

“Artists who could scale,” curator Ruth Berson tells Art & Object, “artists who could come with work the public would engage with. Not necessarily the art cognoscenti, but the kind of people encountering this kind of thing for the first time. We wanted to think about who our local community was and how the choice of artists reflects that. It was less about who are the big names but who's going to speak to the people who actually come here.”

Michael Massenburg, Cultural Playground, 2024. Porcelain enamel on steel panels, 25 x 100 ft.

If you’re arriving at night, you couldn't miss the first artwork if you tried; the actual skin of the dome is covered by artist Jennifer Steinkamp’s “Swoosh”— shifting patterns of multicolored lights.

An Angeleno since 1979 and a former faculty member at UCLA, Steinkamp has built a practice in new media, including video art and 3D animation. “Swoosh” is inspired by the City of Inglewood, Clippers basketball, the wind and sky, and the pounding surf just a few miles to the west.

Patrick Martinez, Same Boat, 2024. Neon tubes and hardware, 9 ft. 5/8 in. x 9 ft. 7 in.

Situated at the corner of Century Boulevard and Prairie Avenue, the site will get eyeballs, not just from foot traffic, but from cars waiting at the light. If you’re headed east on Century, you’ll see Michael Massenburg’s “Cultural Playground,” a 25 by 100-foot porcelain enamel mural on steel panels— a vision of athletes, musicians, and dancers.

A resident of Inglewood, Massenburg is from a generation of artists influenced by the 1965 Watts Rebellion and the Rodney King riots of 1992. Public art commissions include one right up the street at the Kia Forum, former home of the LA Lakers.

If you’re headed west on Century, you’ll see Kyungmi Shin's nearly 23-foot-tall glass and steel mosaic, “Spring to Life,” an abstract composition that begins with a 100-year-old archival photo of the Centinela Springs from Pasadena’s Huntington Library. The springs were central to the Tongva community of Native Americans that formerly occupied the LA area.

Around the corner is Patrick Martinez’s “Same Boat,” a neon sign reading: “We may have all come on different ships but we’re in the same boat now.” Neon sculptures— glowing slogans commenting on social, political, and cultural phenomena— have been a part of Martinez’s practice since the mid-2010s.

Glenn Kaino, Sails, 2024. Concrete, stainless-steel armature, wood, basketball hoops, paint, 41 ft. 7.25 in. x 28 ft. 11.25 in. x 58 ft. 10.5 in.

Dead ahead is Glenn Kaino’s “Sails,” a steel-and-wood, scaled-down clipper ship with sails fashioned from backboards like those found on playgrounds. Kaino’s parents were imprisoned in Manzanar during World War II, a desert camp for Japanese-Americans deemed untrustworthy by the government.

On a visit there, he noticed a battered old backboard and pictured the inmates passing the time with a game of hoops. Further inspiration was drawn from the 1963 effort by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Ambassador Andrew Young to engage young people by visiting communities and playing basketball in the days leading up to the march on Selma.

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Kaino has assembled a body of work from a range of media united in themes of social justice. His pieces have been exhibited internationally and are a part of the collections of LACMA and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, as well as the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Not to be upstaged is a new piece by Charles Gaines, soon to be installed, “Numbers and Trees: Arizona Series 1,” comprising acrylic sheet, acrylic paint, and photographs of trees. At age 80, Gaines spent most of his life in LA and taught at California Institute of the Arts, counting people like Edgar Arceneaux, Andrea Bowers, Mark Bradford, Sam Durant, and Laura Owens among his students.

Refik Anadol, still from Living Arena, 2024. AI data sculpture, 40 x 70 ft.

Across the courtyard is a basketball court with a backdrop by Refik Anadol— “Living Arena,” one of his trademark AI works measuring a whopping 40 by 70 feet.

“I think it’s the largest AI data painting in the world,” says Anadol, who counts the new work as part of his ongoing research into the idea of living architecture— using AI to create visual responses to the environment and memory of a structure. “It’s like thinking about the architecture where we can collect memories, emotions, and environment, taking it beyond concrete, glass, and steel. What I propose is can we give the arena a kind of consciousness?”

Jennifer Steinkamp, Swoosh, 2024. Lights built into the building skin, 950 x 630 x 150 ft.

The emerging and shifting patterns of “Living Arena” are driven by four sources of data filtered through AI: flight data from nearby LAX, area weather patterns, and data from the court inside the arena. “The game itself is the memory of the arena,” observes Anadol. The fourth source is a library of thousands of photos of California landscapes.

“It triggers conversations and makes people think about AI and science and technology,” Anadol says. “It’s not just a visual, it has an impact.”

“Unsupervised,” a piece he did through a similar process at MoMA, mesmerized viewers for an average of 38 minutes, according to his studio’s measurements. “We researched the brain signals of the people and learned that the artwork was creating a positive impact in the mind similar to flow state activations that requires a high mental space, imagination, brainstorming. It’s a state many people enjoy.”

Public art has been a cornerstone of Anadol’s practice since his thesis project, “Quadrature” (2009). This project took computer-driven patterns based on ambient audio in the neighborhood and projected them on the facade of Santralistanbul Art and Culture Center’s main building located in Istanbul, creating a “living sculpture.”

In 2018, he similarly celebrated 100 years of the LA Phil by covering Frank Gehry’s Disney Concert Hall with AI-filtered projections of archival footage.

Kyungmi Shin, Spring to Life, 2024. Stained glass mosaic and waterjet cut stainless steel, 22.75 x 7.5 ft.

“Maybe this form of art helps us connect or disconnect. That, to me, is one of the most important parts of the work. It inspires, sometimes, joy,” Anadol smiles. “It’s fascinating to have public art in the practice. It’s one of the highest forms of art, because it’s for anyone and everyone.”

Shin, who has works in LA, Washington, D.C. and San Francisco, among other cities, also spoke on this type of art. “Public art is tricky, because the community usually wants something conservative and nothing politically controversial. So, it's a challenging practice. Sometimes you feel like they just need a particular type of work. But, it makes you shift your focus and think about how the artwork makes the site better. It really made me a better artist, a bigger thinker.”

Berson is just happy to bring art to a public audience that might not otherwise engage with it. “Basketball fans are going to come back again and again and see more each time. Hopefully, they’ll think, ‘I'll go to a gallery next time, maybe I'll spring for a museum,” she shrugs. “I’ll seduce people into art anyway I can.”