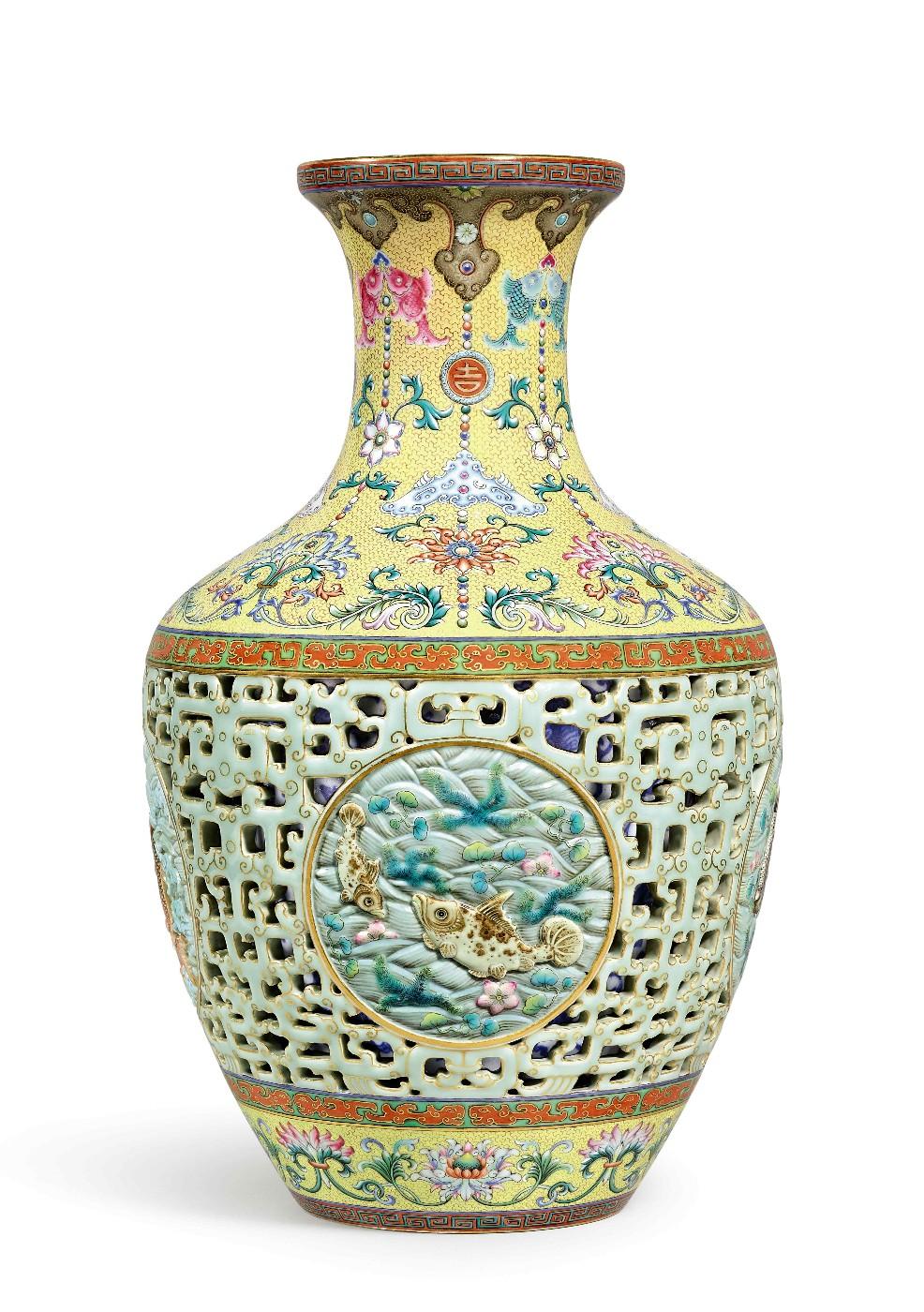

Nicolas Chow, Chairman, Sotheby’s Asia, International Head and Chairman, Chinese Works of Art, comments, “It is a great privilege for us to offer this Qing reticulated vase from the Imperial collection of the Qianlong Emperor this season. Not only is the vase unique and elaborate in design, it is also in pristine condition. To think, the distance the singularly fragile vase has traveled, and the tumultuous times it has survived, for it to be standing here in front of us today without so much as a crack or a chip, is truly extraordinary.”

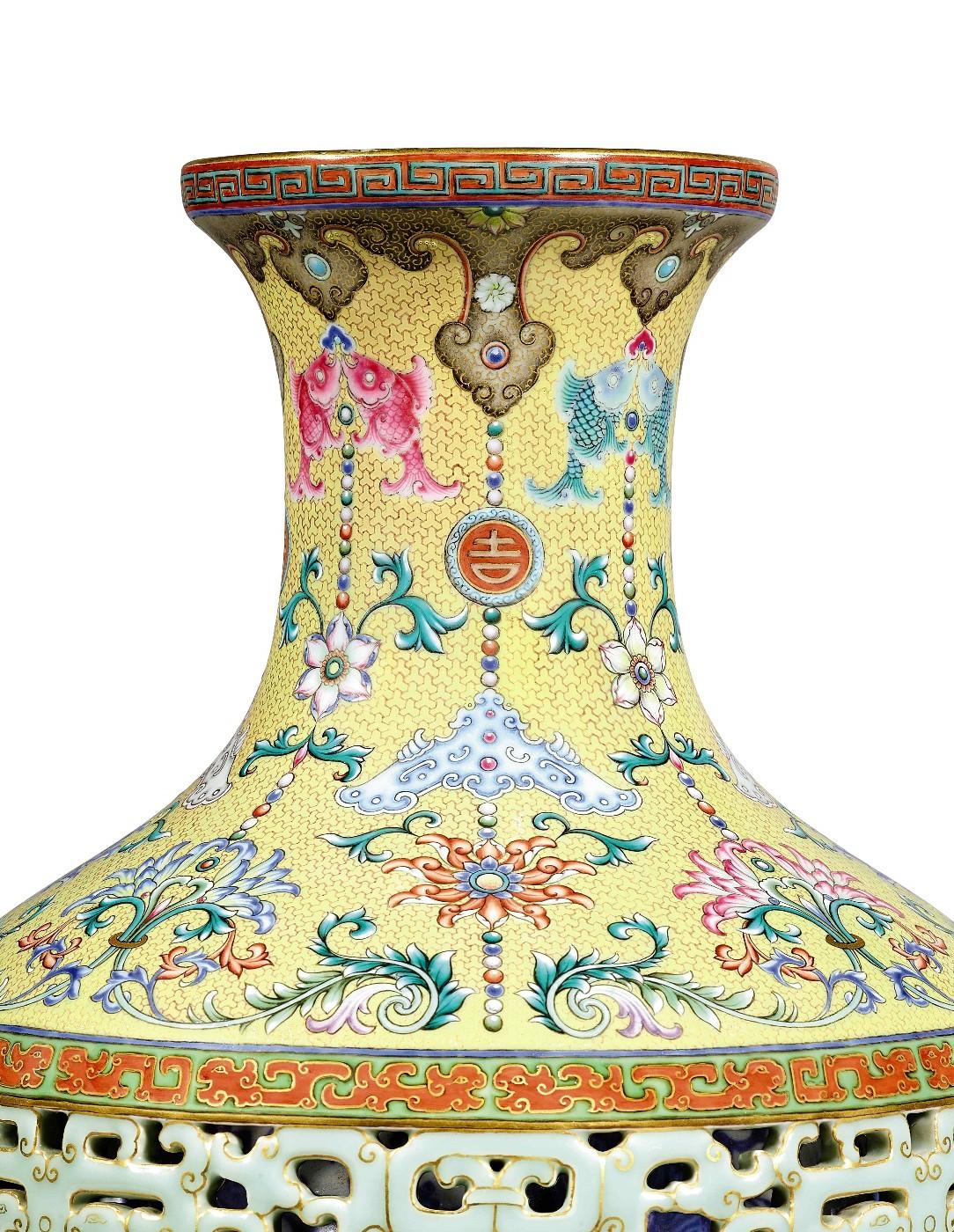

This porcelain masterpiece is not only a reflection of the exacting standards on technical proficiency and the insatiable demand for stylistic novelty at the court of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1795); but an aesthetic representation of the cultural confluence of East and West at its pinnacle in Chinese history.

Prominently featuring an openwork design composed of highly stylised archaistic dragons, borrowed from archaic ritual bronzes of the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046 – 256 BC), the vase’s openwork-side and double-wall design can be traced back all the way to the official (guan) kilns of the Southern Song Dynasty (c.1127-1279) at Laohudong (Tiger Cave Kiln) in Hangzhou, where excavated shards correspond with the original prototypical model of such a design. Extant examples can still be traced back to the Yuan Dynasty (c.1271–1368) at the Longquan kilns in Zhejiang. The present design with its pale green glaze clearly echoes these prototypes and the style is in fact expressly referred to as ‘Longquan’ in the Qing imperial records, where an entry for 1743 documents a pair of yangcai yellow-ground reticulated vases with ‘Longquan openwork design’, for which stands were to be made. When peering through the reticulated outer shell of the vase, the Emperor could see inside a blue-and-white vase with composite flower scrolls, of a type that recalls the exquisite Yongle porcelains of the early Ming dynasty made at Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province.