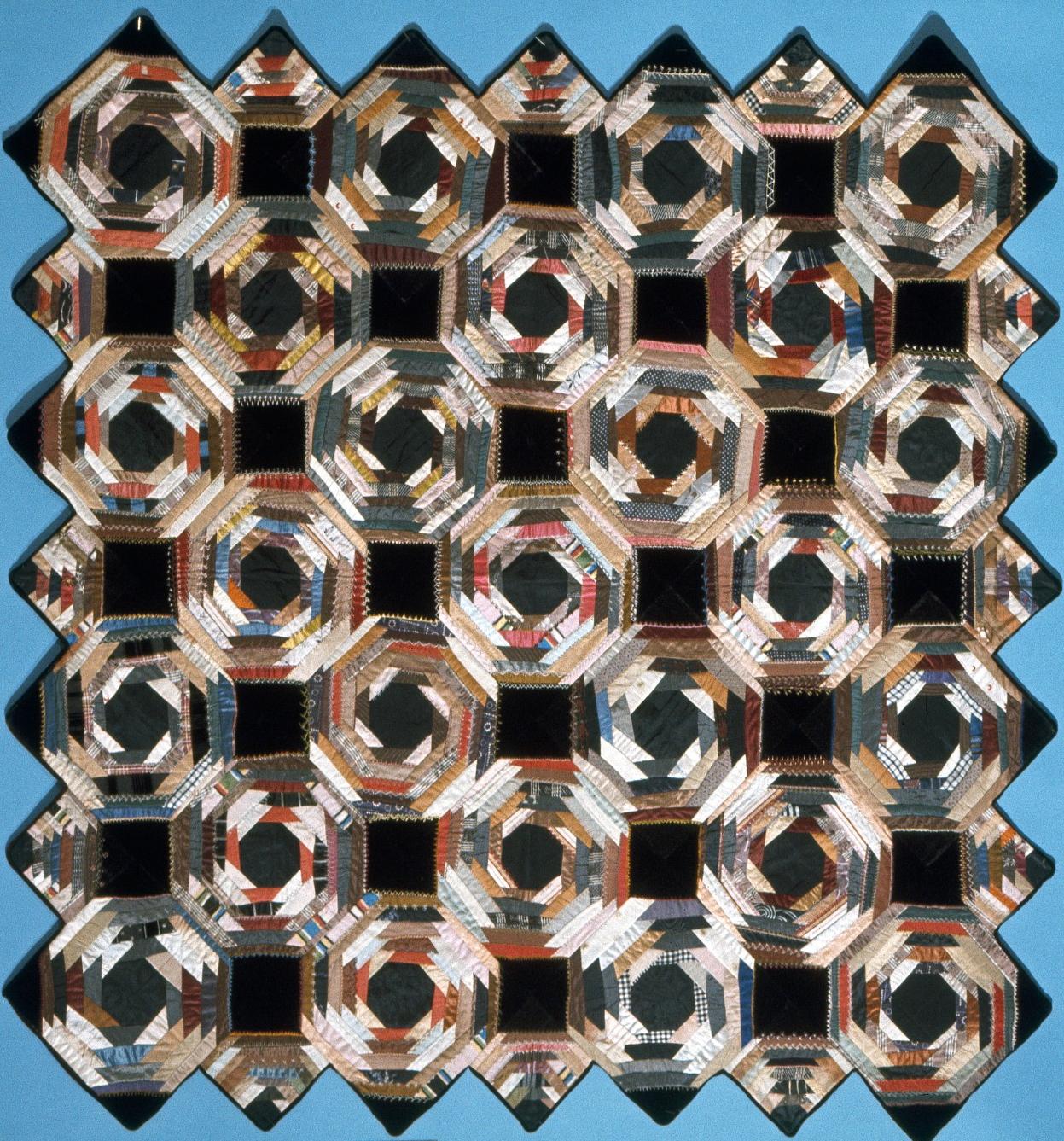

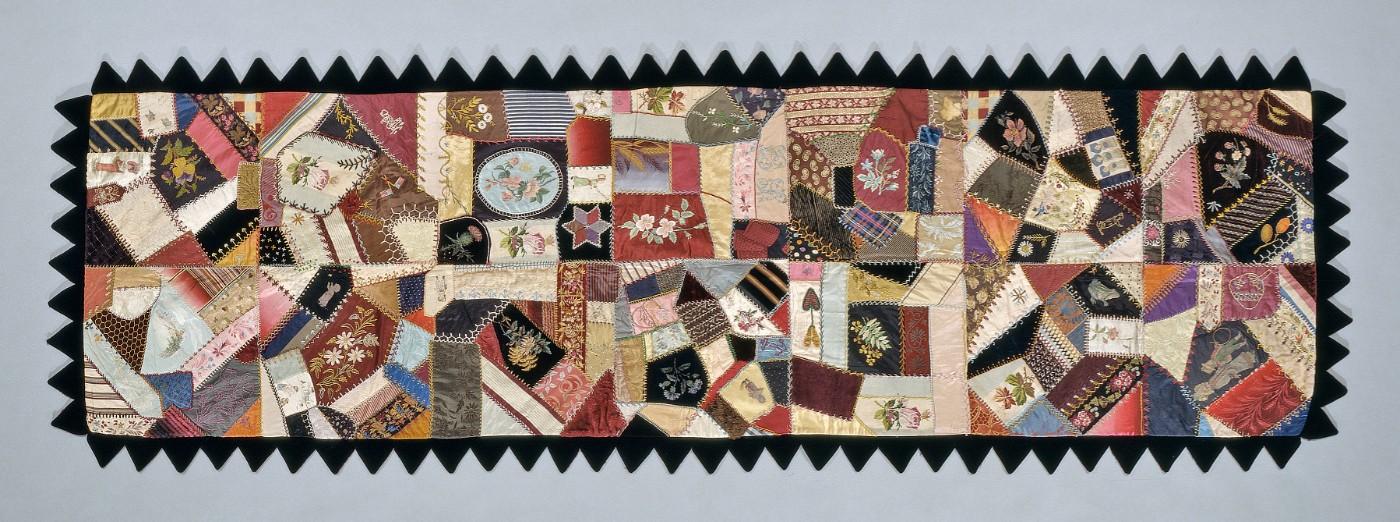

Inspired by the availability of inexpensive silks, a new fad emerged nationwide in the 1880s for ‘crazy patchwork’ quilts. Quilt makers adopted asymmetry and layered patterning, moving away from the rigid geometric piecework of traditional quilts. Silk embroidery added dimensions and texture to the quilts. These quilts were never meant to be used as bedding. Instead, they were a statement of status and style at the turn of the 20th century. They tell a little-known story of art, industry, trends and marketing in American history.

“The quilts on display demonstrate individual imagination and skill,” said exhibition curator, Madelyn Shaw. “But beyond that, they represent America’s silk industry: thousands of mill workers, hundreds of companies, business people and designers. The quilts offer us a unique perspective on this period of industrialization in American history.”

Silk is the continuous filament a silkworm makes to create its cocoon. About 3,000 cocoons make one pound of raw silk. To turn silk filaments into yarn, cocoons are placed in simmering water to dissolve the gummy substance binding the fibers together. A worker (reeler) whisks up the ends of several filaments and draws them off the cocoons together, forming a very fine thread called “raw silk.” A process called “throwing” combines several raw silk strands into yarns strong enough for sewing, embroidery, weaving and knitting. American yarn and fabric manufacturers bought cocoons and raw silk primarily from Japan, China and Italy.