Images from those early days of concentration camp liberation, showing the emaciated victims of torture that had managed to survive the Nazi death camps, are shocking and unforgettable. Through the written accounts of survivors and these black and white photographs and films we can begin to fathom the depravity of the concentration camps. A new exhibition is adding another voice to those accounts.

Peter Loewenstein, Eight Men in Coats with Stars, 1944. Ink on paper.

As World War II came to an end, Allied troops crossing Europe discovered the depths of the horrors of the Holocaust. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the largest and most deadly of the Nazi concentration camps, where more than 1.1 million people were murdered. Soviet troops entered the camp on January 27, 1945, a day now recognized as International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Ceremonies across Europe, including one at the Auschwitz Memorial Museum, marked the occasion.

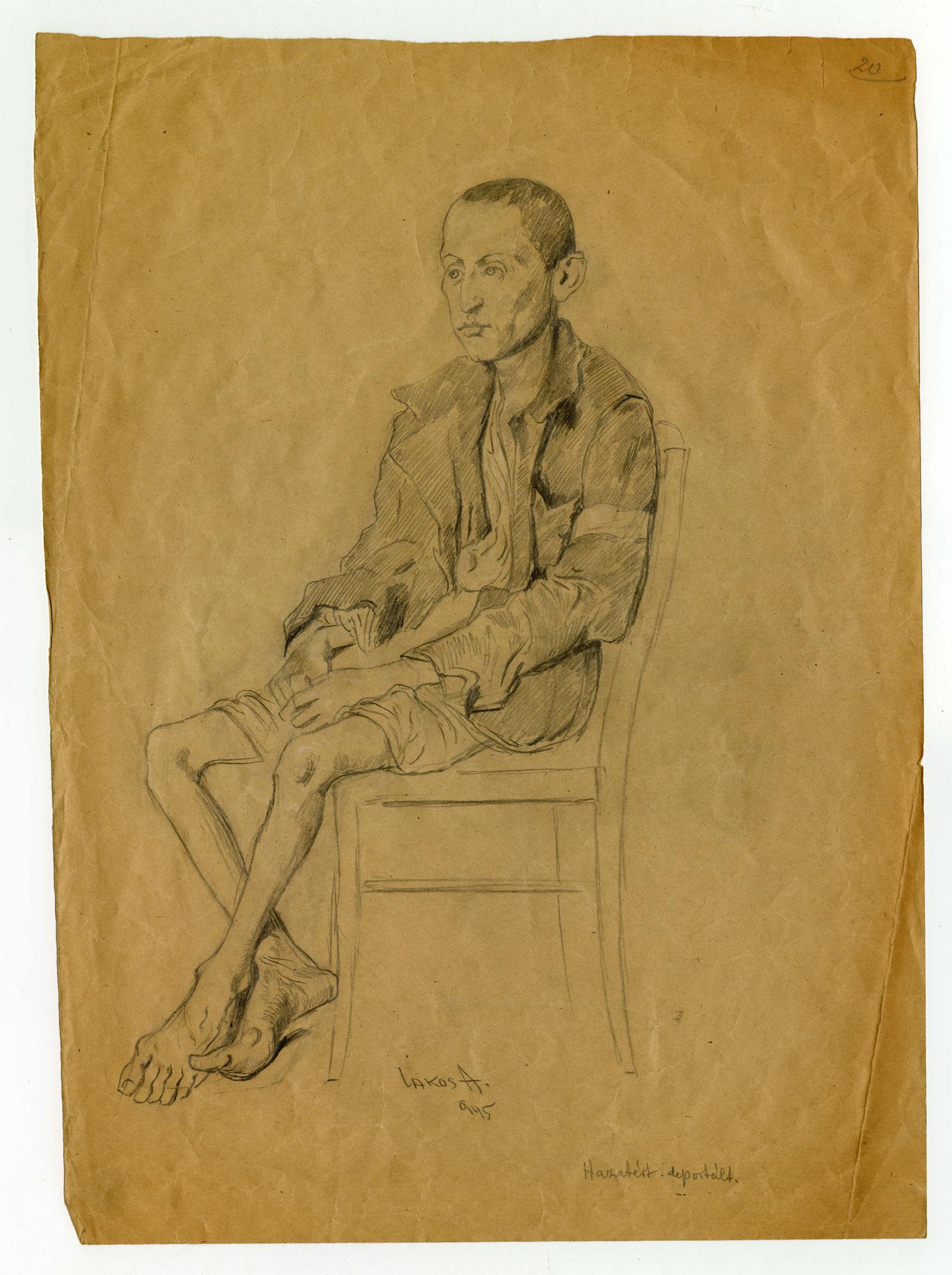

Alfred Lakos, Returned Deportee. Pencil on paper.

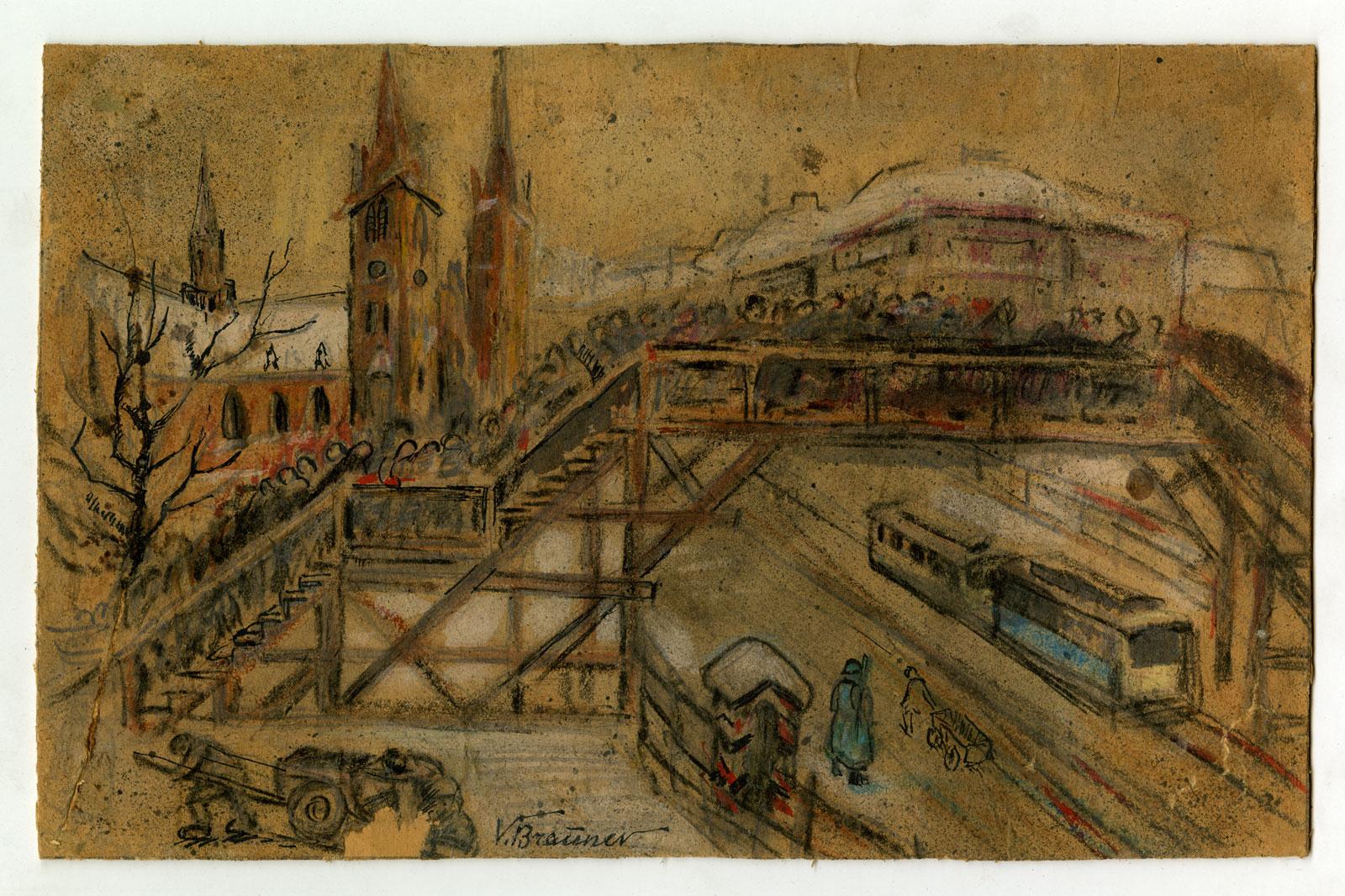

Vincent Brauner, Lodz Ghetto Bridge, c. 1940-1943. Pen and ink, watercolor, and conté on paper adhered to wood.

At the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, Rendering Witness: Holocaust-Era Art as Testimony showcases the visual art created by Holocaust victims during and soon after their imprisonment. Drawn from the museum’s collection, the twenty-one artworks on display are primarily drawings on paper, and show the diversity of prisoners and of experiences within the camps. Victims of the Holocaust are often lumped together as one homogenous group, but these works, created in slave labor camps and ghettos in Czechoslovakia, Germany, Hungary, and Poland, reveal this fallacy.

“The art on display in Rendering Witness demonstrates that every victim of the Holocaust has a personal story,” said curator Michael Morris.

Alfred Kantor, Electric Barbed Wire. Pencil, crayon, and collage on paper.

Alfred Kantor was a prolific artist who extensively documented life in Auschwitz, and later the Schwarzheide and Terezin camps. A Jewish physician risked his own well-being by giving Kantor a miniature watercolor set and letting him paint in the infirmary. He later said, “…I felt obsessed, driven in fact by the overwhelming desire to put down every detail of this unfathomable place [Auschwitz]. I began to observe everything with an eye towards capturing it on paper…” Though Kantor destroyed much of his work created during the war for fear of being discovered, after liberation, he meticulously documented his experiences, creating what would be called the “The Book of Alfred Kantor.”

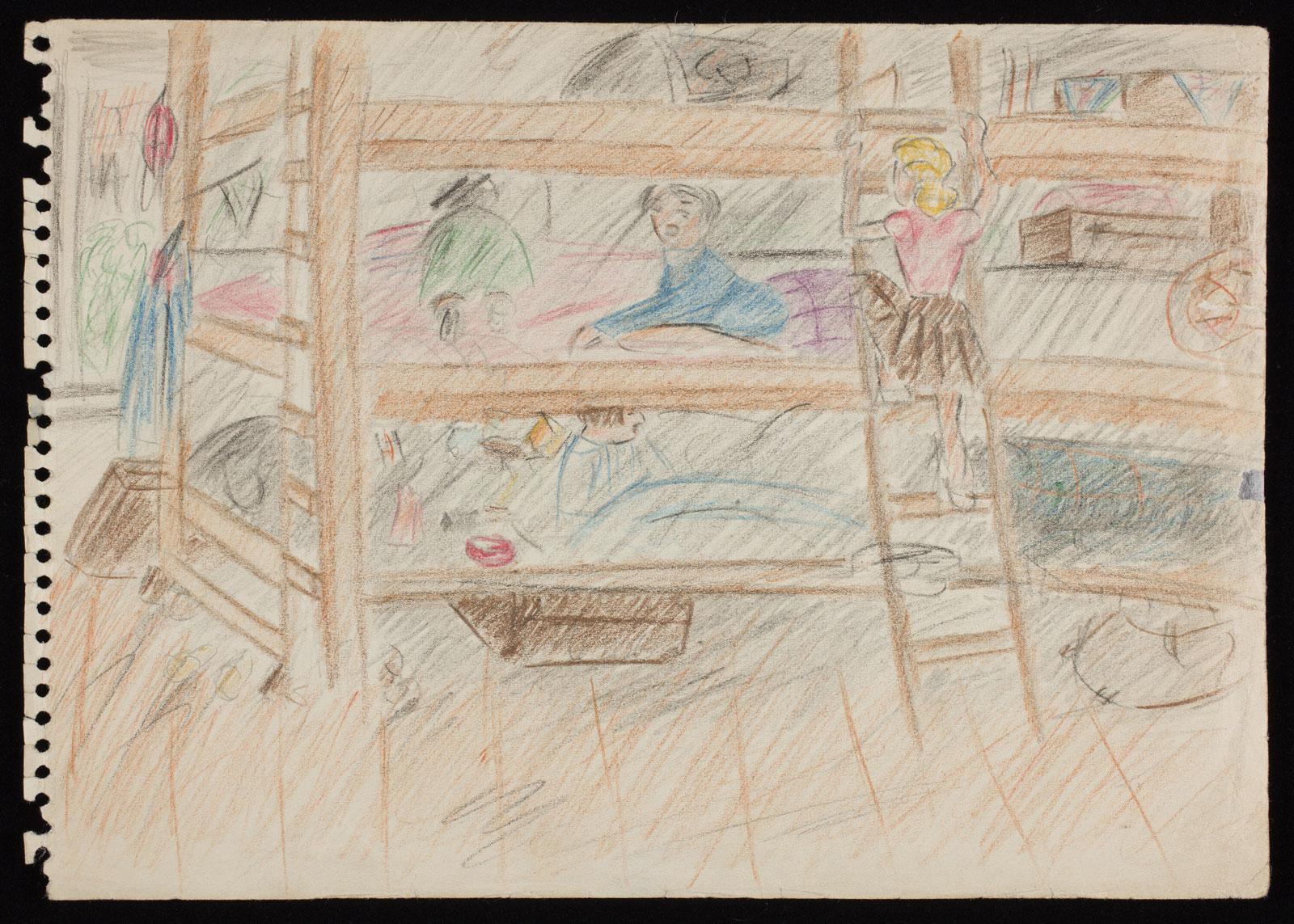

Helga Weissova, Children’s Home L410. Colored pencil on paper.

Helga Weissova was, at only 12, merely a child trying to cope with new horrors around her. Her colored pencil drawing of the children’s barracks she lived in reminds us that even children were not spared from these atrocities. Weissova would create more than 100 drawings that were hidden in camps and returned to her after the war.

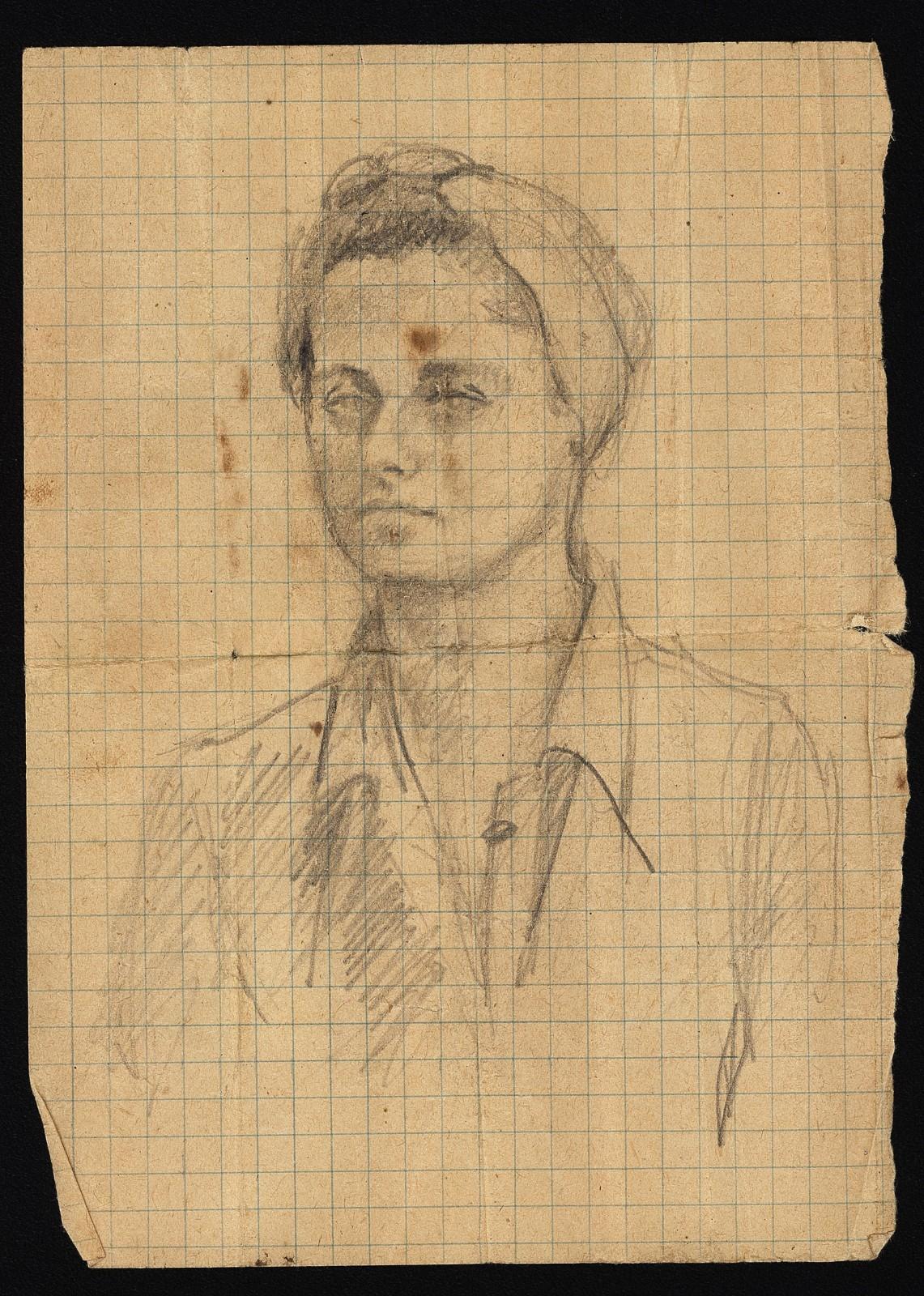

Kantor and Weissova were lucky to survive the concentration camps, while so many were not. A portrait of Susan Weiss, drawn by fellow prisoner Manci Anis, made it out of the camps with its sitter. This surviving work is perhaps all that is left of Anis–her fate of remains unknown.

Manci Anis, Portrait of Susan Weiss. Pencil on paper.

Given that this type of expression was punishable by torture or worse, these works show the deep human need to express ourselves and to document our experiences. “These were tremendous acts of bravery and resistance. That these fragile works have survived is a testament to the human spirit,” said Jack Kliger, Museum President & CEO.

Rendering Witness: Holocaust-Era Art as Testimony in on view at the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust in New York City through July 5, 2020.