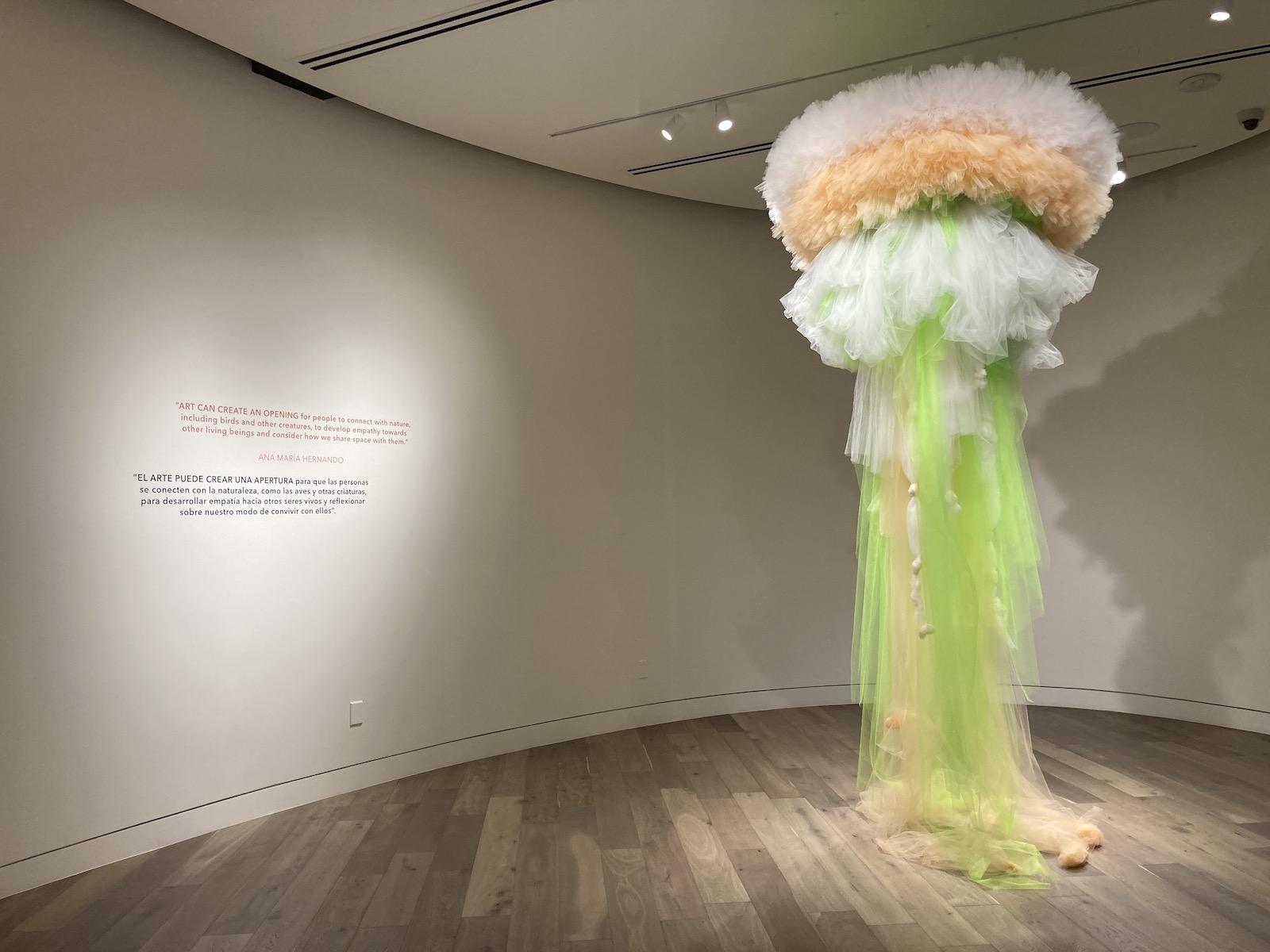

Hernando’s exhibit, titled Fervor: Illuminating the Spirit of Nature, displays monumental, site-specific installations of tulle—yards and yards of tulle, soft and translucent. A towering, flower-shaped sculpture trailing lime green strands of tulle—an allusion to stems—holds court in one gallery. In the adjoining gallery, a mountain of tulle—earthy brown and ochre with a snow-white peak—stands soft yet stalwart beneath a billowy tulle cloud.

Installation View of Fervor: Illuminating the Spirit of Nature

In a perfectly paired yin-yang juxtaposition of exhibitions, two artists—Ana María Hernando and Yoshitomo Saito—show works inspired by nature, yet rendered in extremely different media. Hernando works in tulle and other textiles. Saito sculpts bronze using the lost-wax method. These contemplative exhibits in the galleries of Denver Botanic Gardens might cause a viewer to compare and contrast the soft and hard, the feminine and masculine, the shape and size of these artworks.

Both artists immigrated to the United States—Hernando from Argentina and Saito from Japan. Coincidentally, both attended the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, CA.

Saito reflects, “That particular school pushes students to be genuinely cultural and highly intellectual when handling materials. The important backdrop was the level of racial, cultural diversity of the Bay Area. A peculiar edgy feeling is always there between people to make them anti-conformist, in general. The good aspect is, the friction from the various conflicts produces a new creative energy for all.”

The creative energy evident in these exhibitions is nonconformist, particularly in the artists’ use of media.

Installation View of Fervor: Illuminating the Spirit of Nature

Installation View of Fervor: Illuminating the Spirit of Nature

Hernando’s exhibit includes a birdsong soundtrack. “Birds are disappearing in such enormous quantity, and the first to go are the birds that sing because they are less aggressive. I decided to record the birds before they disappear and give that to the mountains as a gift,” she says.

In the gallery, suspended, diaphanous squares flap gently like variations on Tibetan prayer flags. Embroidered by Hernando and occasional companions, the squares hold designs based on sound clips collected and sent to the artist during the 2020 lockdown.

Previously, Hernando has collaborated on embroideries with cloistered Carmelite nuns from Buenos Aires. In the gallery, the wispy squares

“I’ve worked almost twenty years with these nuns. I had 215 little embroidered pieces. In sculptural work, people expect stone or metal—hard materials that I don’t use. Fabric doesn’t have the longevity of stone,” says Hernando, who took an early interest in fabrics at her grandparents’ textile factory.

In addition to textile installations, Hernando creates works on paper and wood, paintings and assemblages, as well as dimensional collages and art books.

Conversely, Saito has worked almost exclusively in bronze for the past thirty-five years. The works in his exhibit titled Of Sky and Ground took him ten years to complete.

In an artist’s talk, Saito noted that bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, was discovered about 5,500 years ago as the first man-made metal. “The Iron Age took over because it was better for utilitarian weapons and tools, but bronze is much longer-lasting than iron,” explained Saito, who went on to emphasize the traditional role and strong statements created by bronze memorial statues.

“The material is expensive. Labor is expensive. Energy is expensive, so bronze is for special occasions, to commemorate significant people and events and relate information to later generations,” he added. “A bronze sculpture is often huge. People in every culture look up to it.”

Yoshitomo Saito, Wings of Fairy, bronze, 2021.

Conversely, for his nature poetry series, Saito sculpted “ordinary, down-to-earth, small things, broken-off fragments of nature.” His exhibit includes bronzes inspired by tree branches and insect wings.

The most impressive installation is millionyearseeds, which consists of 1,728 small sculptures wall-mounted in a wave that resembles a murmuration of starlings, a dragon, a sweep of dark shapes forming a larger configuration. Along with life-sized pinecones and pomegranates, Saito sculpted realistic banana peels, chili peppers, seed pods, twigs, and mushrooms—each casting shadows on the white wall.

Yoshitomo Saito, millionyearseeds, bronze, 2011-2021.

Saito acknowledges the influence of Japanese wabi-sabi aesthetics of imperfect perfection on his work, “The more I age, the more I know it’s with me and under my subconscious—the essential aspects of pathos and poignancy, but this piece is more about prayerfulness and joyfulness I discover in each form. It’s a parade, not a funeral procession."

Denver Botanic Gardens has cultivated a tradition of hosting marquee art exhibits: Henry Moore, Alexander Calder, and Dale Chihuly, to name a few.

The gardens’ art curator Lisa Eldred says, “The aim is to highlight and celebrate the many ways humanity is inspired by, connects with, and responds to the natural world. Nature permeates and influences artists. Hernando’s soft fabric works acknowledge birds and connections between people and, at the same time, celebrate feminine strength and power. As a counterpoint, Saito’s inspiration from seeds and leaves falling materializes in the durable, yet soft medium of bronze.” Eldred concludes, “The two exhibitions complement one another, offering examples of how artists and humans, in general, can respond to nature.”