The SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia is housed in a historic building that once served as a depot for the Central of Georgia Railway, the only surviving antebellum railroad complex in the United States. One very long gallery features a succession of archways along one side composed of Savannah Grey Brick, a unique over-sized brick dating to the 1800s that were hand-formed by enslaved people on a plantation called the Hermitage on the Savannah River. Along the other side of the gallery is a clean modern wall of windows.

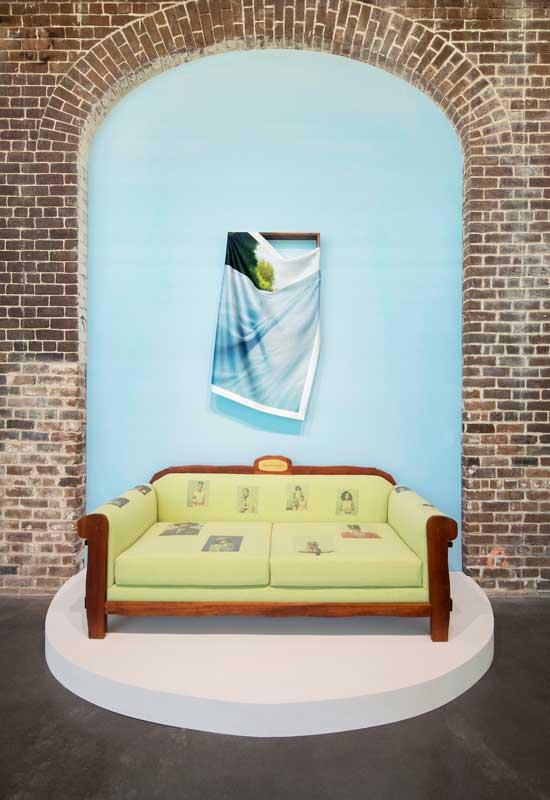

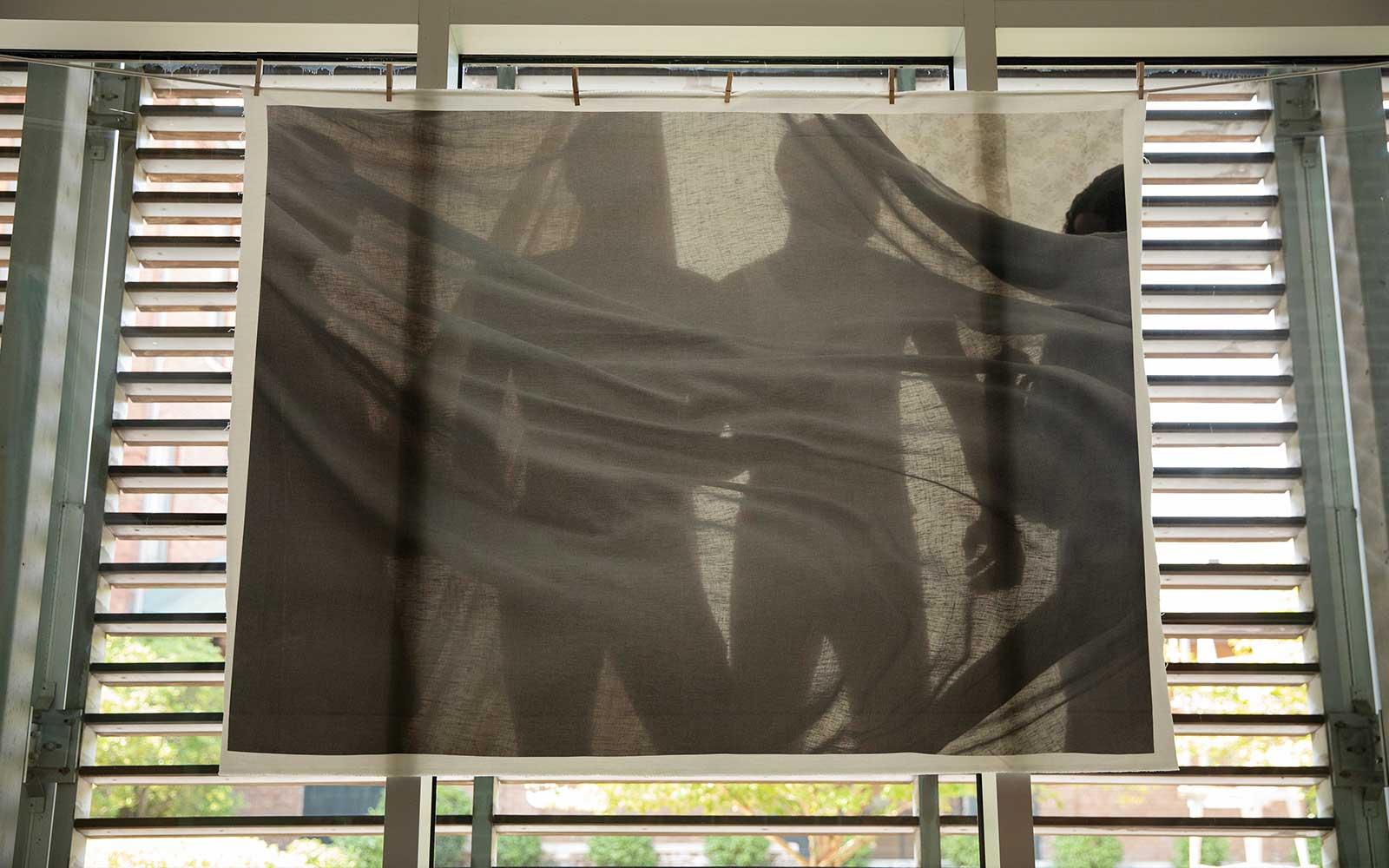

It's against this backdrop that artist Tyler Mitchell’s exhibition, “Domestic Imaginaries” is staged. The exhibition features a showstopping 300-foot-long clothesline that starts at one end of the gallery and zig-zags clear through to the other end. From this meandering line, textiles of varying sizes and materials are hung with clothespins, each one featuring a photograph taken by Mitchell.

The photos in this work, called Threaded Memory, are mostly abstracted images of young Black people at rest or play, or sometimes doing quasi-domestic tasks like washing sheets, done nonetheless in a way that exudes a sense of presence and joyfulness. You might see a foot stepping on grass or a couple of people huddled intimately behind a sheet, or a swath of nothing but exquisitely blue sky. Leaving the blinds open, with the sunlight streaming through the windows, Mitchell has invited the outdoors in to mingle with his work, and allow the viewer to experience the elements as his subjects do, to allow the two spaces to converge.

Some of the textiles are light and transparent allowing the sunlight to permeate, while others are heavier and opaque. It’s difficult to get a grounding view of the whole space. The viewer has to begin a journey through the clothesline and have the show unfold as one navigates, sometimes tilting your head back to view smaller works hung very high.

While his own childhood—Mitchell was born and raised in Georgia, where he lived in the same home for 18 years—was one filled with leisure and green space, he sees what a luxury outdoor space and free time have historically been, especially for Black people.

“I really started to think about leisure time, the great fortune of leisure time I’ve had growing up in the South as a real luxury and as actually what I want to be talking about,” Tyler told Art & Object. “And the idea that free time, leisure moments of reprieve of rest, more inward meditation—I’m not talking about meditation as the institution or practice—whatever that means to the self. That those moments are the ultimate luxury.”