A spectacular exhibition organized jointly by London’s National Gallery and Berlin’s state museums, on view in 2019 at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, is the first to be devoted to these two stars of the Italian Renaissance. The London and Berlin museums possess the best collections of Mantegna and Bellini outside Italy, so a collaboration made sense. Among the top-drawer loans were three Mantegna masterpieces from the British Royal Collection, The Triumphs of Caesar, which usually hang in Hampton Court.

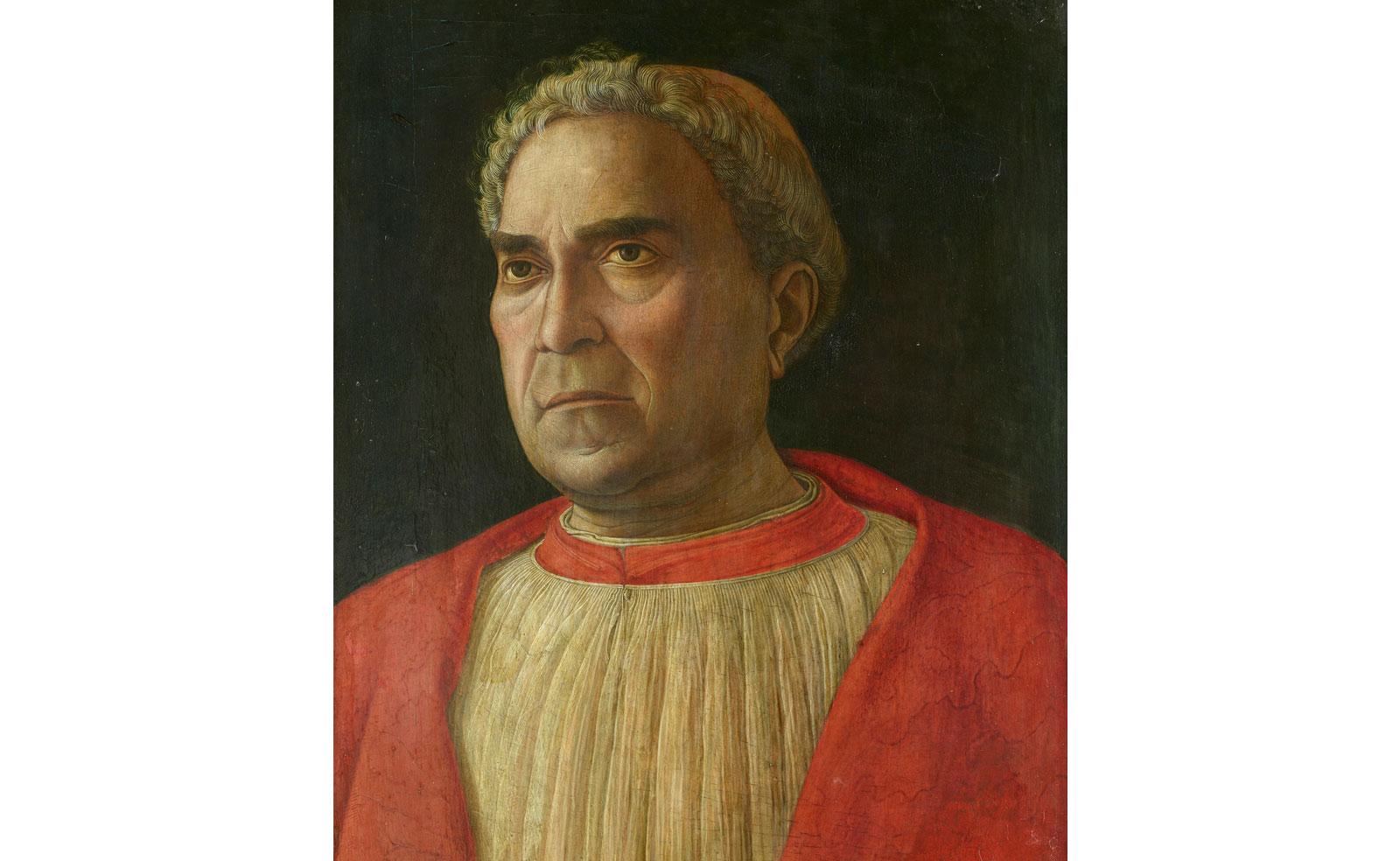

The exhibition invited a contrast-and-compare approach, and both the similarities and the differences are striking. Perhaps the most concrete evidence of the influence Mantegna wielded over Bellini is in their paintings of The Presentation of Christ in the Temple, here shown side-by-side. Mantegna’s egg tempera on canvas work dates from about 1454 and possibly marked his wedding or the birth of his first child. It is an intimate close-up of Mary passing the swaddled baby Jesus to a curly-bearded Simeon. Joseph looks on between them, while two peripheral characters in the background (thought to be likenesses of Nicolosia and Mantegna) look past the scene into the distance to the left of the viewer.

Recent research has revealed that Bellini traced Mantegna’s painting to produce his own oil-on-panel version as many as twenty years later. Yet it also has distinct differences. He added two more peripheral characters, removed the haloes and changed Mary’s robe. The colors are warmer, the skin-tones softer, and both Joseph and Simeon look less grizzled and more kindly.

Why Bellini chose to copy, then change the work of his brother-in-law is a riddle that has occupied scholars for many years, as have the unknown identities of the two additional figures. But if imitation is the highest form of flattery, his painting can only be viewed as a touching fraternal tribute to Mantegna’s brilliance–in an era that predates copyright law.

The years before and after Mantegna’s marriage into the Bellini family, between about 1450 and 1460, were the period when the artistic exchange between the two artists was at its most intense. Both created versions of The Agony in the Garden during this time, and they are among the first painted works portraying Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane after the Last Supper, the apostles sleeping as he prays. Though the compositions are different, Bellini borrowed some of Mantegna’s techniques, such as the use of powdered gold in drapery and haloes. But the power of Mantegna’s work lies in its sculpted precision and solemnity, while Bellini’s poetic landscape of gentle hills and a bubbling river is suffused with the pink light of dusk.