The images exhibited at Met Breuer show Arbus exploring much of the same territory that street photographers, including Walker Evans, Paul Strand, Winogrand, and Friedlander, occupied. Her subjects and style evoke the photographic flâneur Eugène Atget, who shot the streets of Paris in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; Berenice Abbott, Helen Levitt, and Weegee, all of whom made New York their subject; and Robert Frank, whose acute observation of American culture in his 1958 book, The Americans, forever transformed how America was photographed.

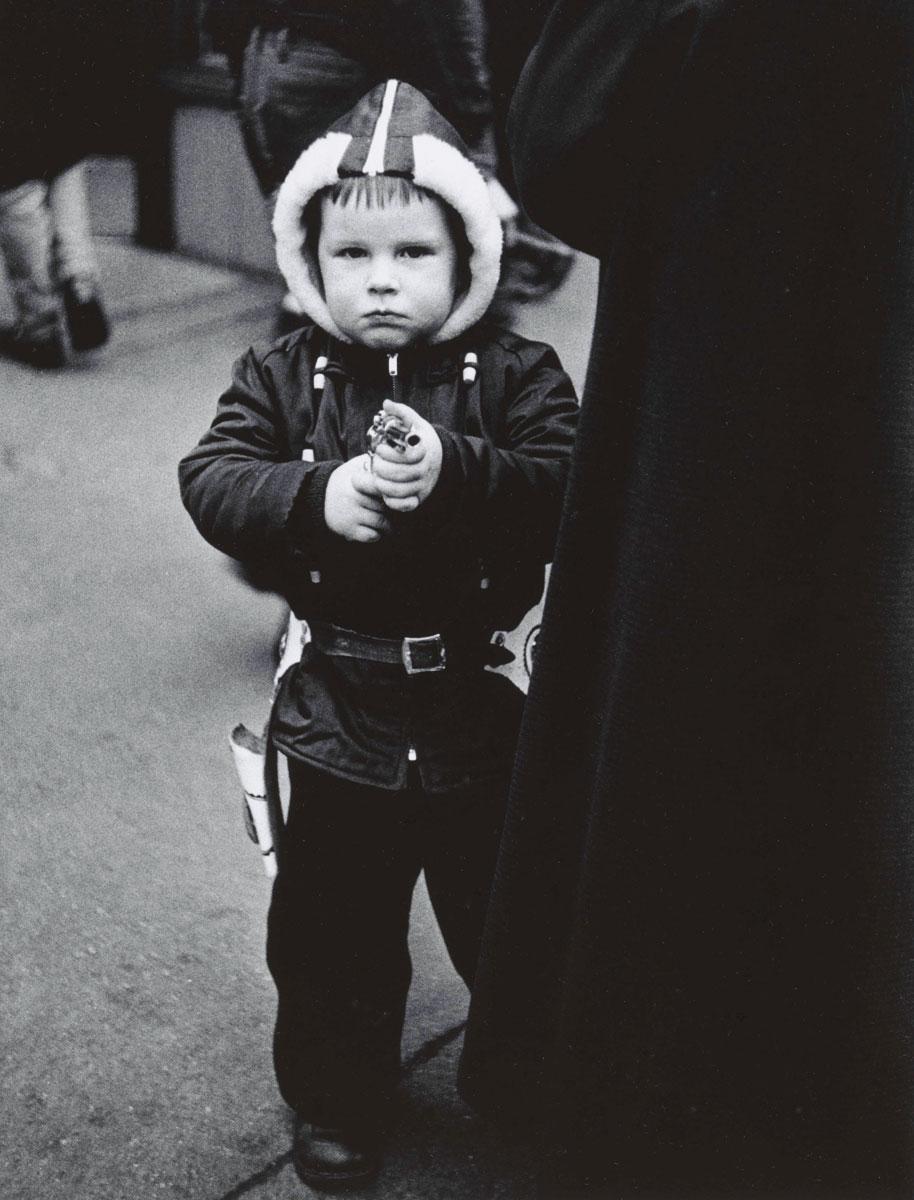

Arbus’ street photography, however, works within and pushes beyond the genre’s usual subjects. Woman with white gloves and a pocket book, N.Y.C., 1956, recalls Weegee, who Arbus once accompanied while he shot. Kid in a hooded jacket aiming a gun, N.Y.C., 1957, is reminiscent of William Klein. But on the street, Arbus seems to want more from her subjects than to observe at a distance. In Girl with schoolbooks stepping onto the curb, N.Y.C., 1957, a school-age girl, wearing a plush-collared coat and pom-pom hat, with books in hand, looks directly at the camera, which is just paces from her.

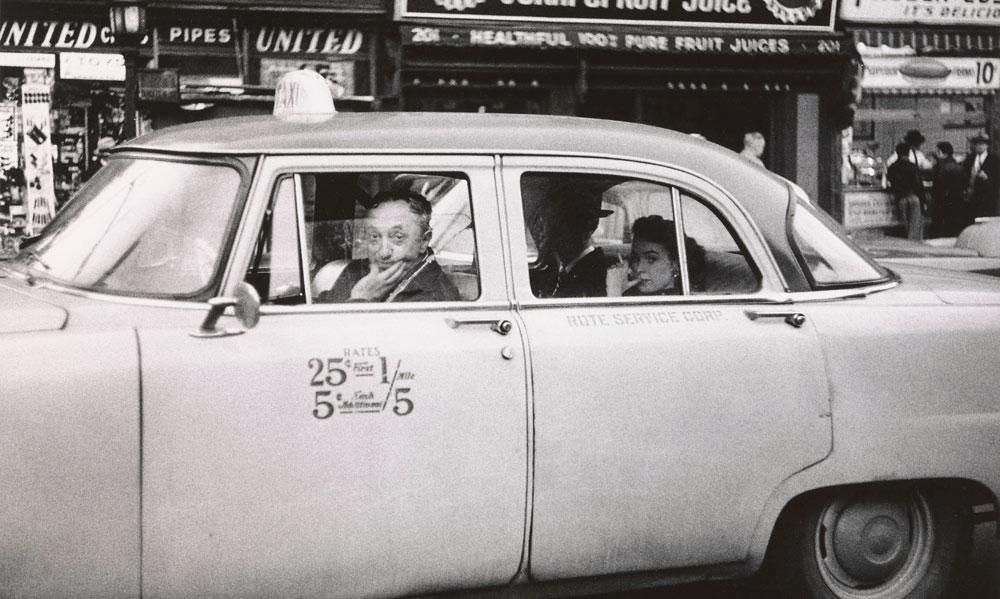

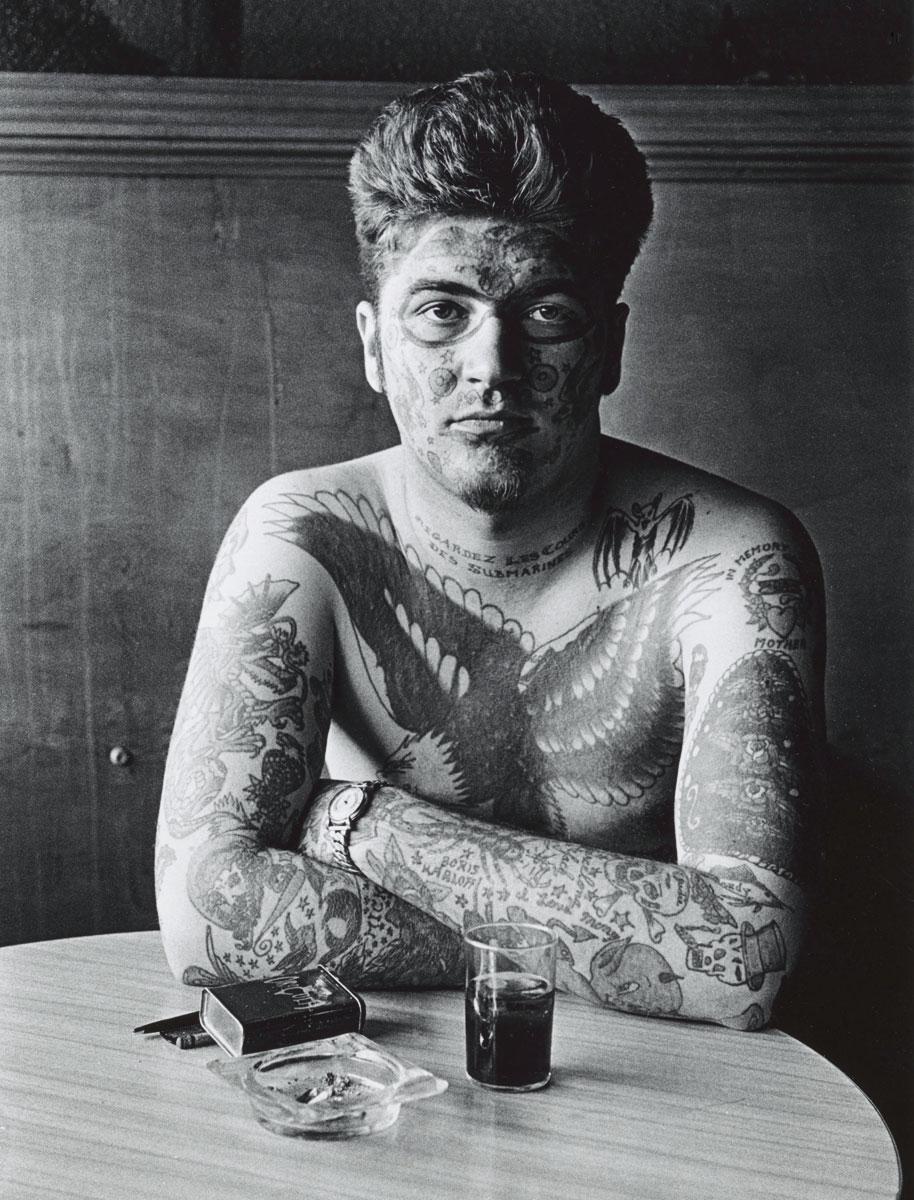

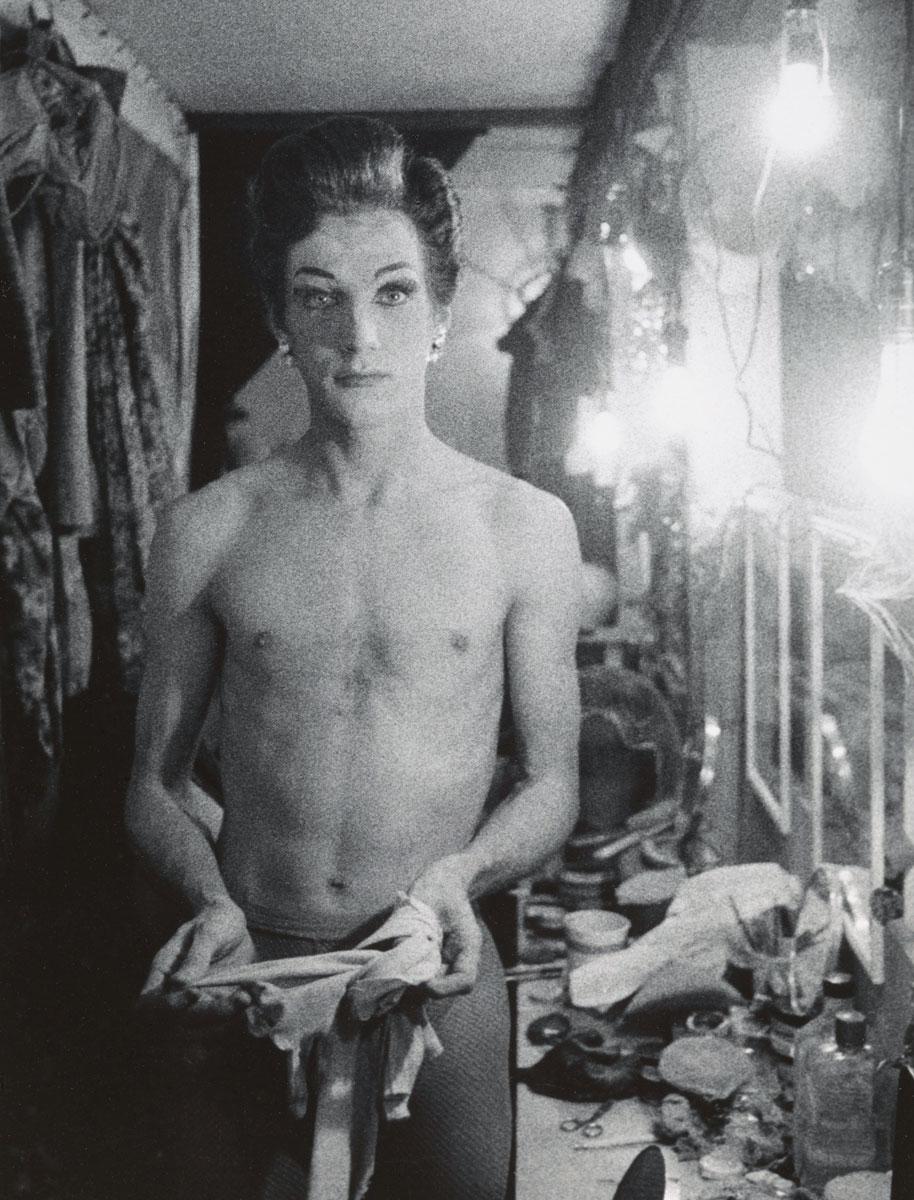

In photographs of circus performers, beach bathers at Coney Island, and female impersonators in their dressing rooms, the photographer’s curious and unsettling voyeurism is already evident, but so is her intense engagement with her subjects, who, almost as a rule, look directly at her. Like Evans, who concealed a camera in his coat to shoot on the New York subway, Arbus wanted to be close to her subjects. But she wasn’t interested in concealing herself or her camera—quite the opposite. There’s an insistent closeness in these images, as if she were testing how near she could get to her subjects, visible, for example in Lady on a bus, N.Y.C. 1957, where Arbus is so close to the woman it feels like she’s just swiveled in her seat to get the shot. In return, that unnamed woman looks straight through Arbus, her camera, and, by extension, us.

Shot with 35-millimeter film, these images—made without a light meter—are grainy, smoky, gritty. She’d found her subject matter, but yet to find her style. Around the time she published her first photo-essay in Esquire in 1960, Arbus was introduced to August Sander’s sharp and composed portraits of German social types from the 1920s. Wanting to emulate the clarity of his portraits, she started to use a Rolleiflex with a wide-angle lens in 1961. The camera’s larger negatives, 2 ¼ inches square, almost four times larger than 35 millimeter, provide far more detail; this changed her pictures. She worked in both formats, trying out the Rollei to shoot soothsayers, bodybuilding competitions, and beauty pageants. A year later, she was making the pictures that became her signature, including Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. 1962. Tense and jittery, it’s pure Arbus.

In 1963, with Model’s encouragement, Arbus applied for a Guggenheim Foundation grant, following in the footsteps of Evans and Frank. Arbus wrote that she wanted “to photograph the considerable ceremonies of the present because we tend while living here and now to perceive only what is random and barren and formless about it.” She wanted to “gather them, like someone’s grandmother, putting up preserves, because they will have been so beautiful … I want simply to save them,” she wrote, “for what is ceremonious and curious and commonplace will be legendary.”