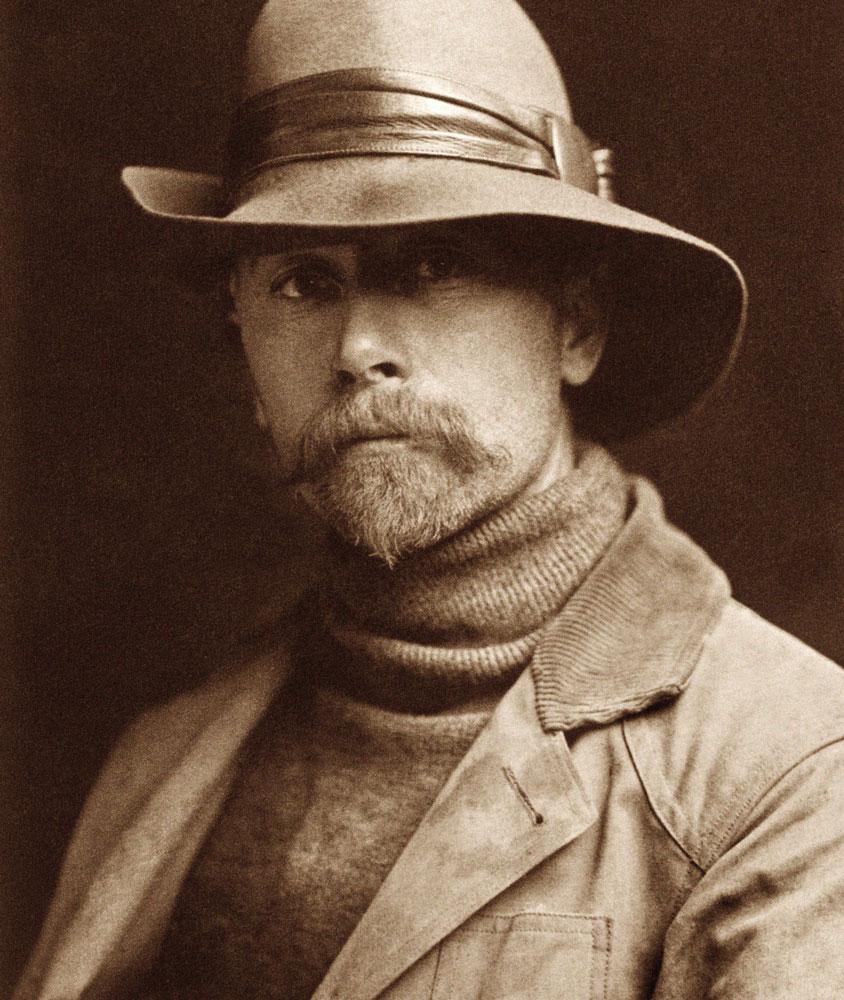

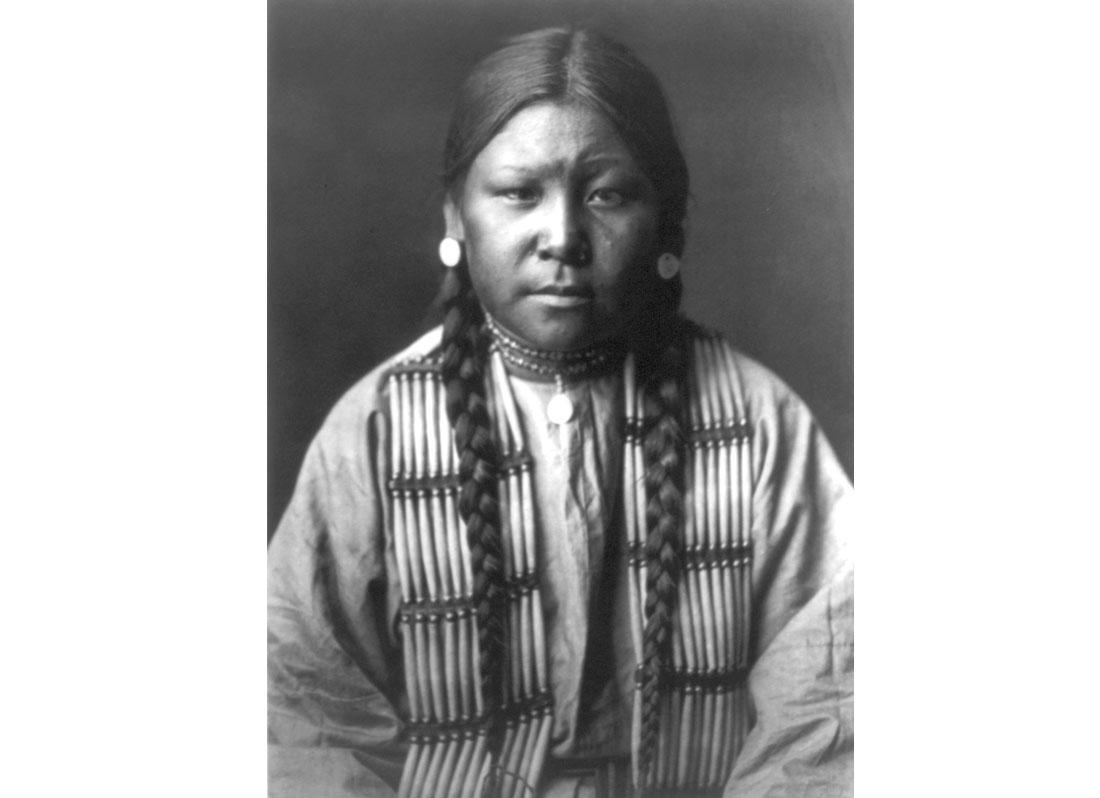

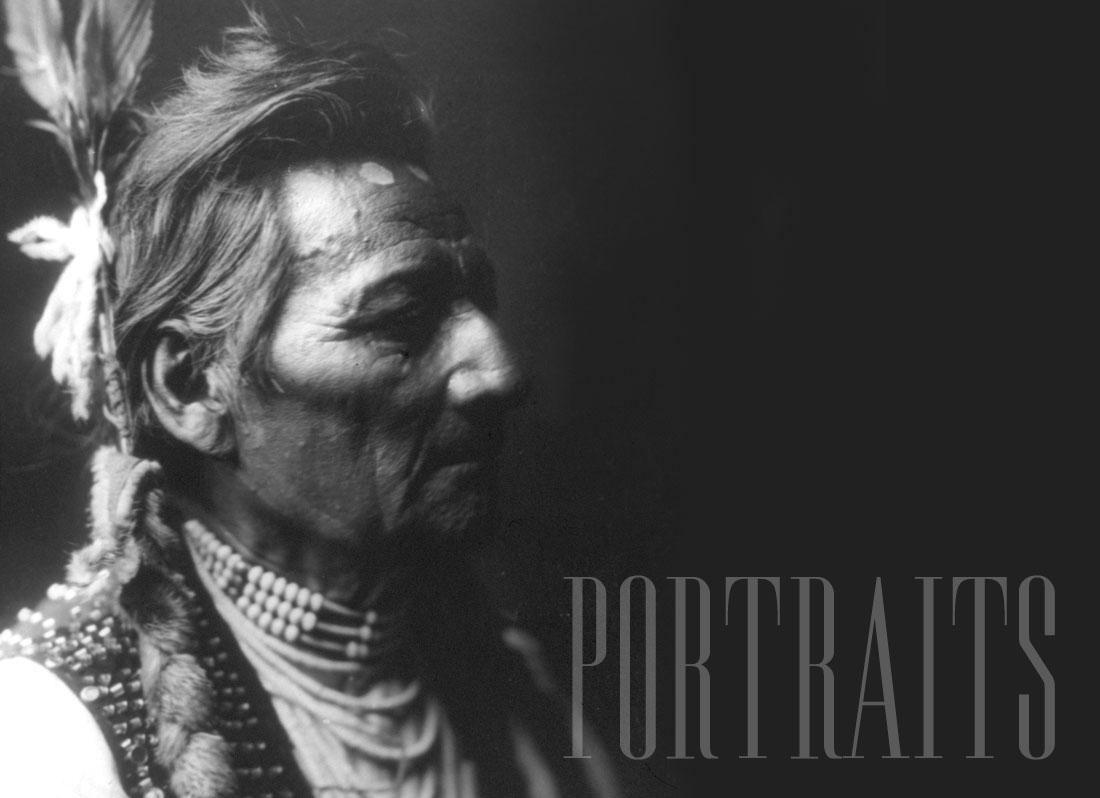

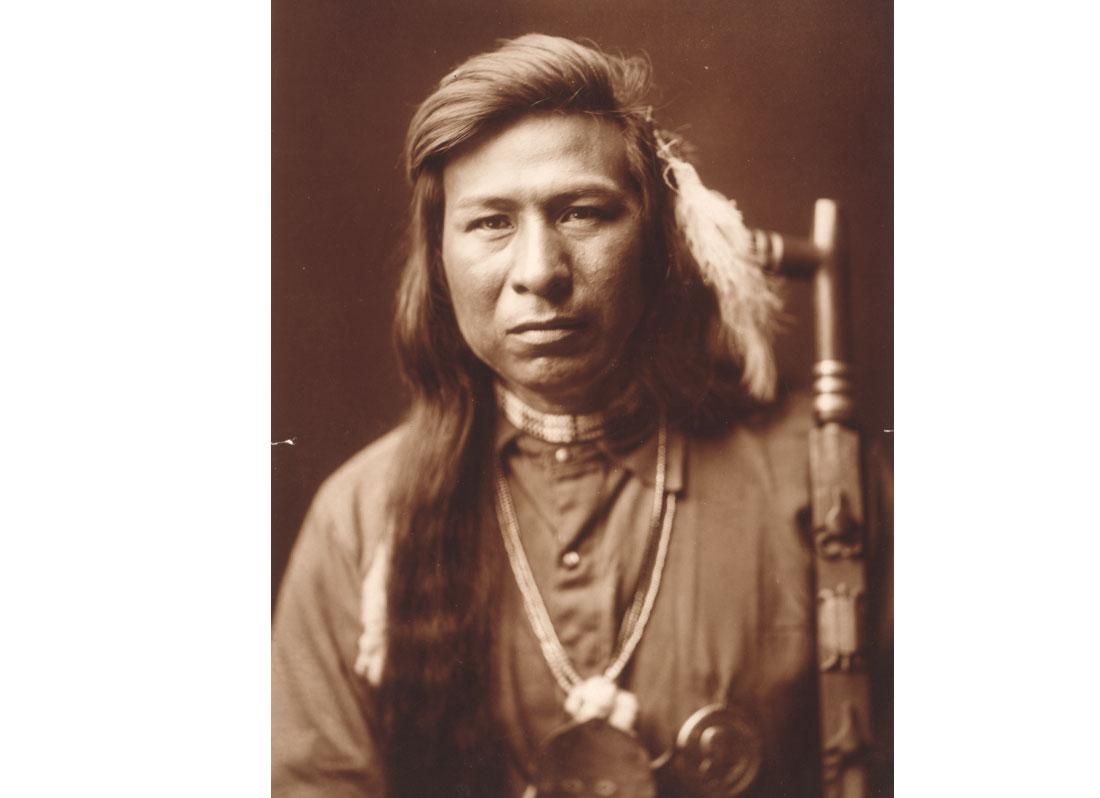

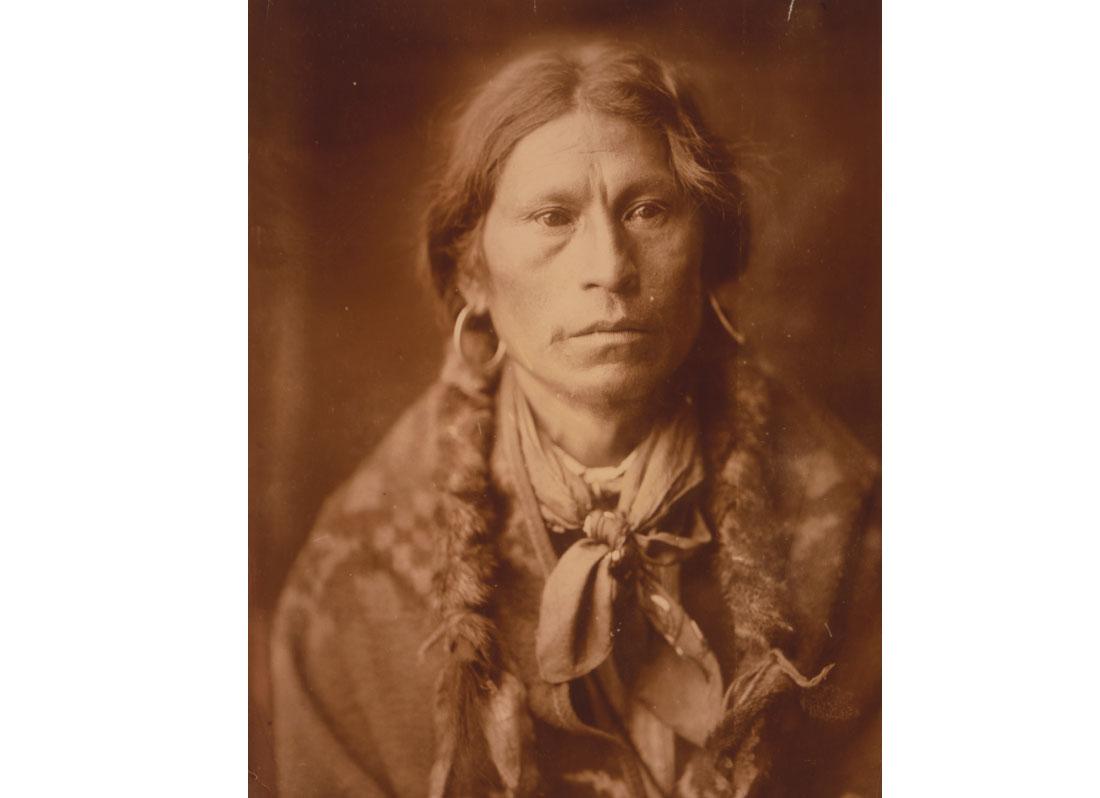

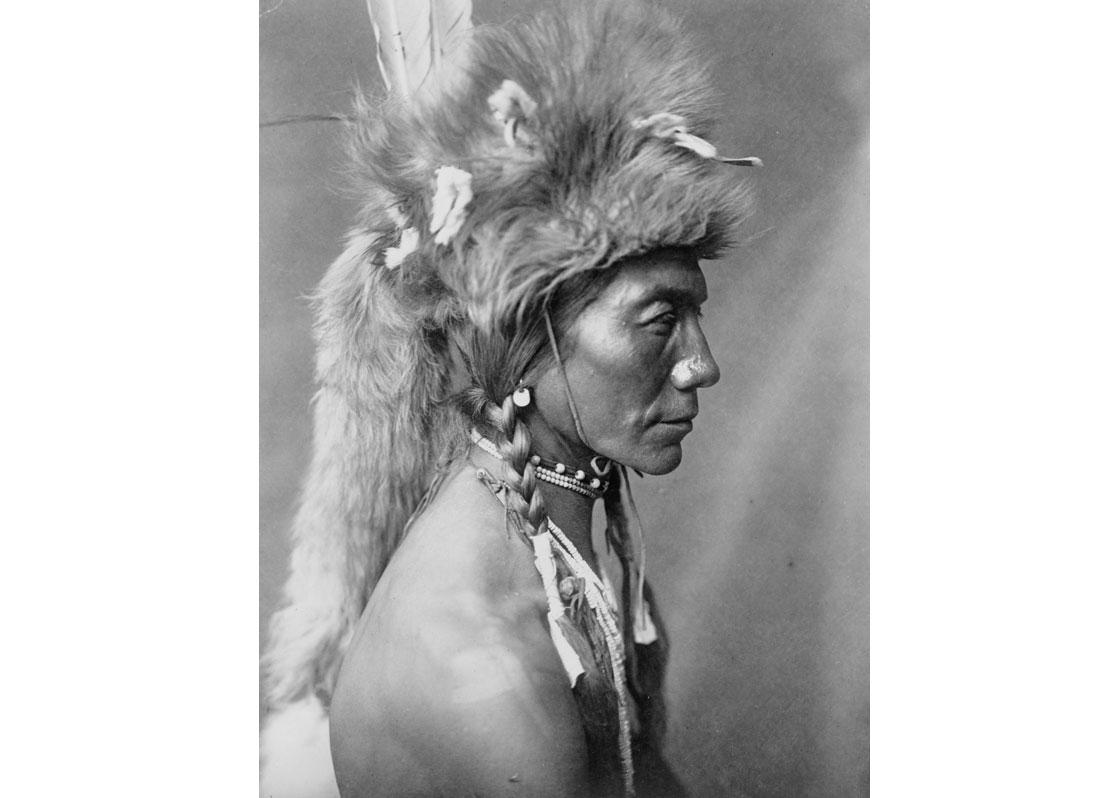

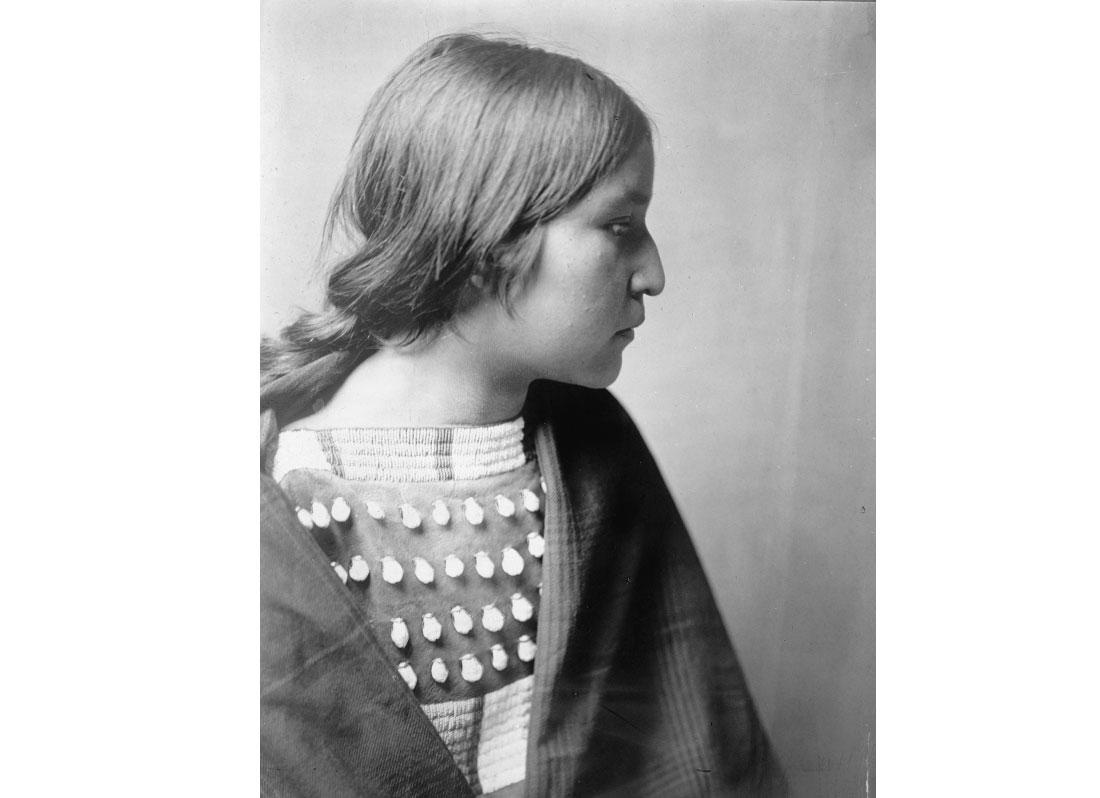

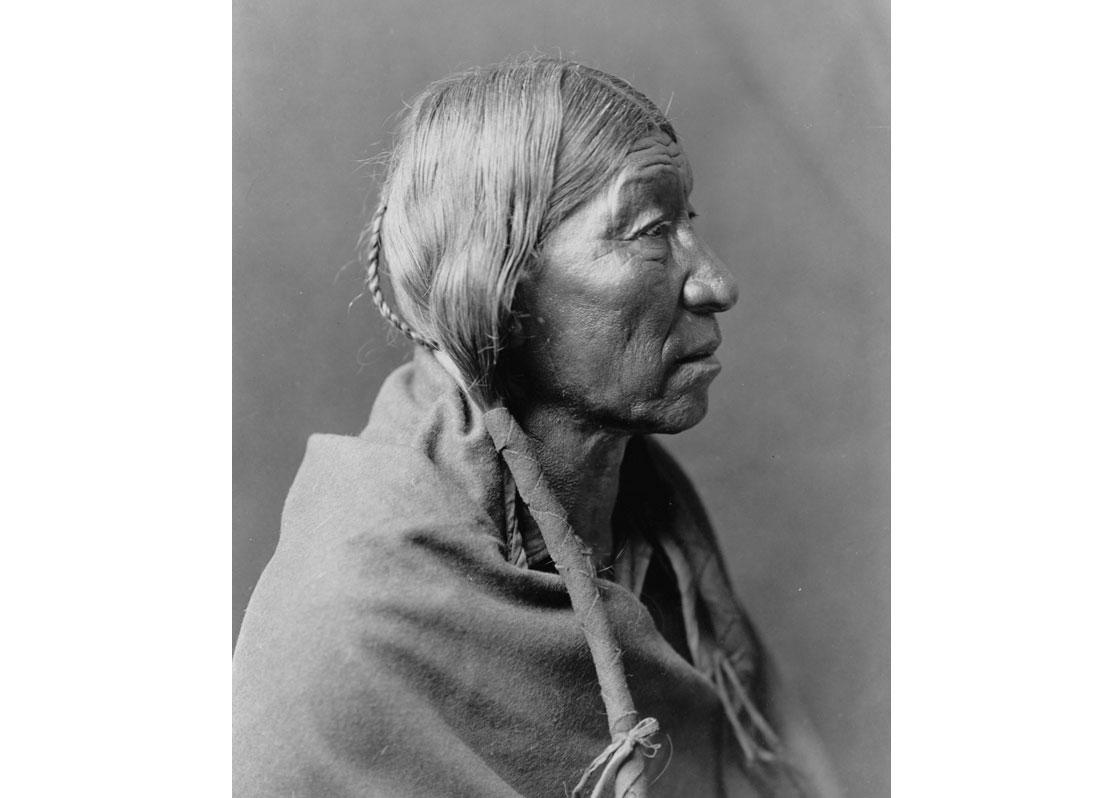

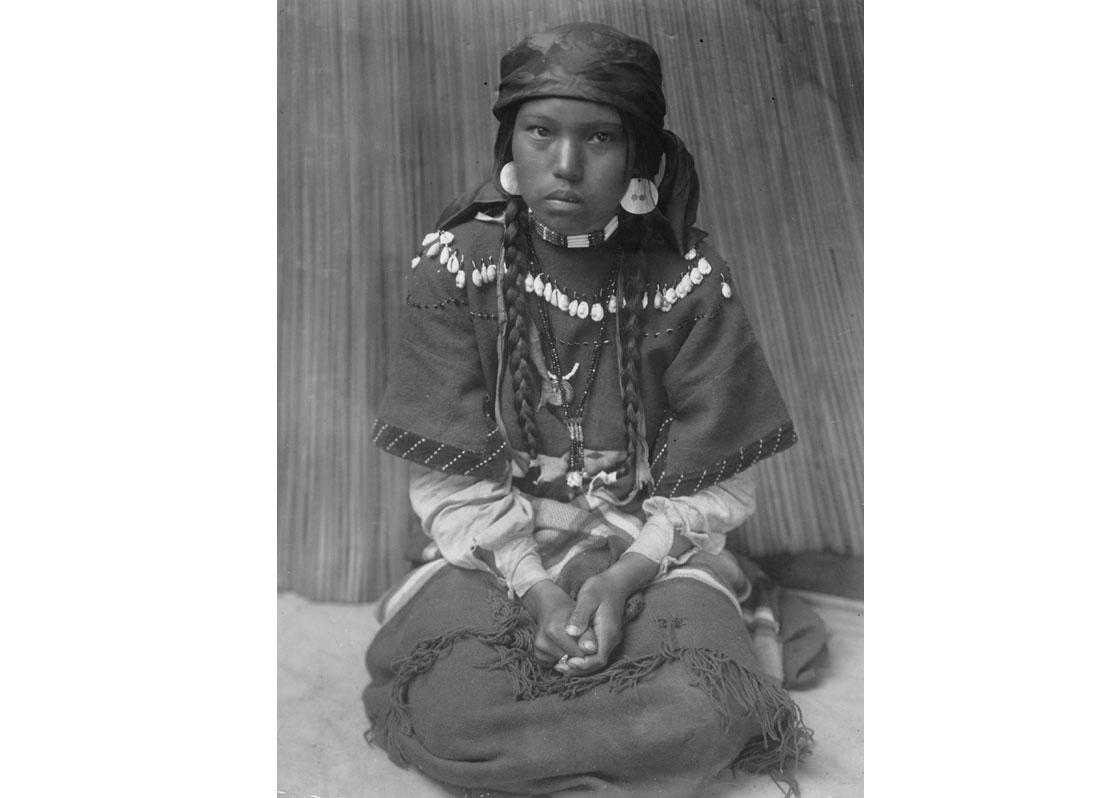

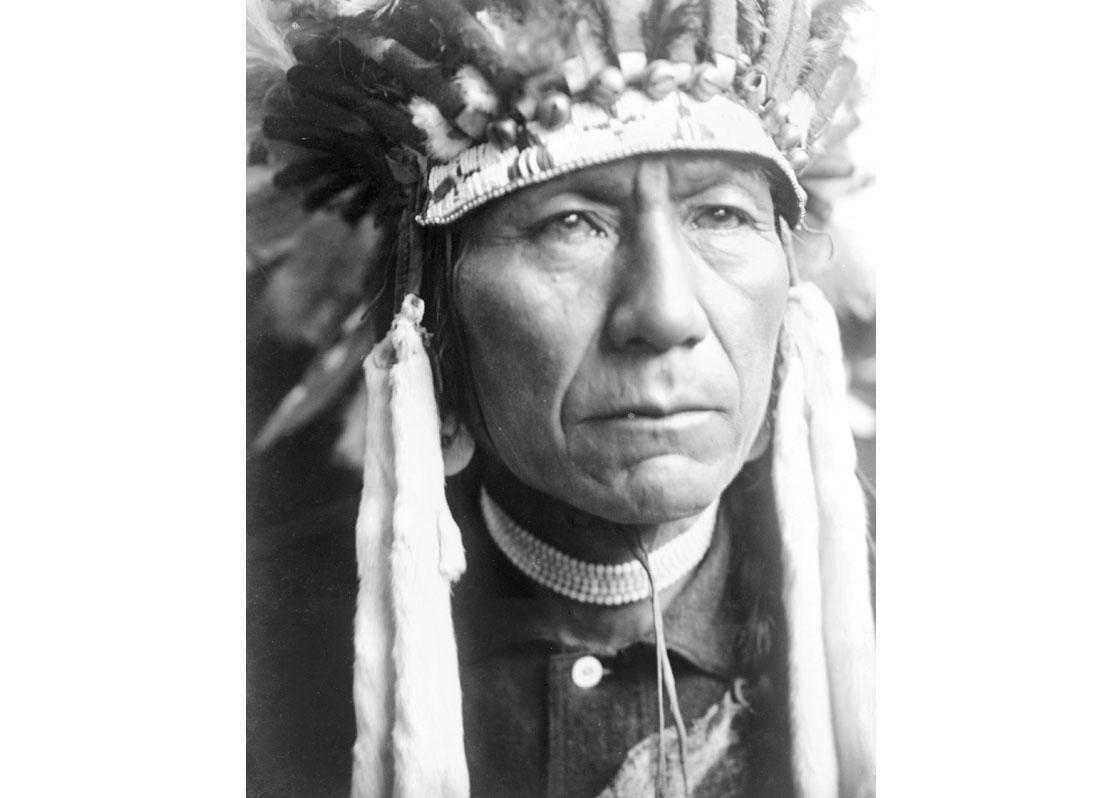

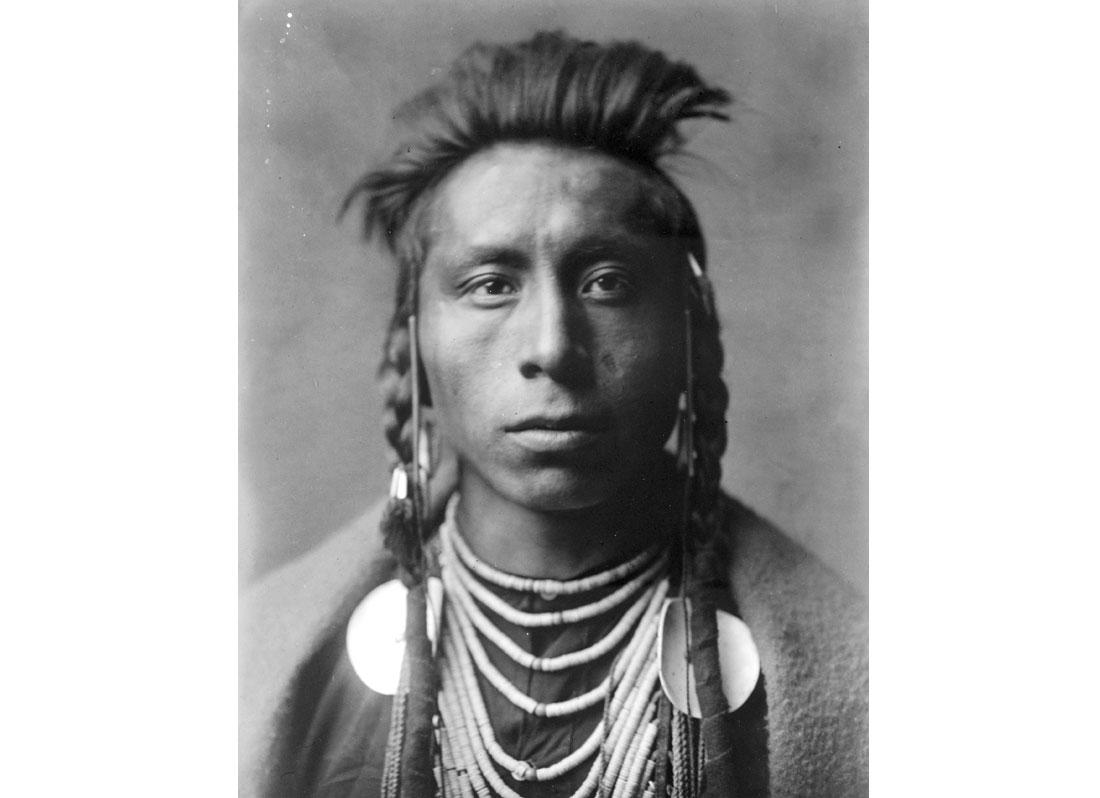

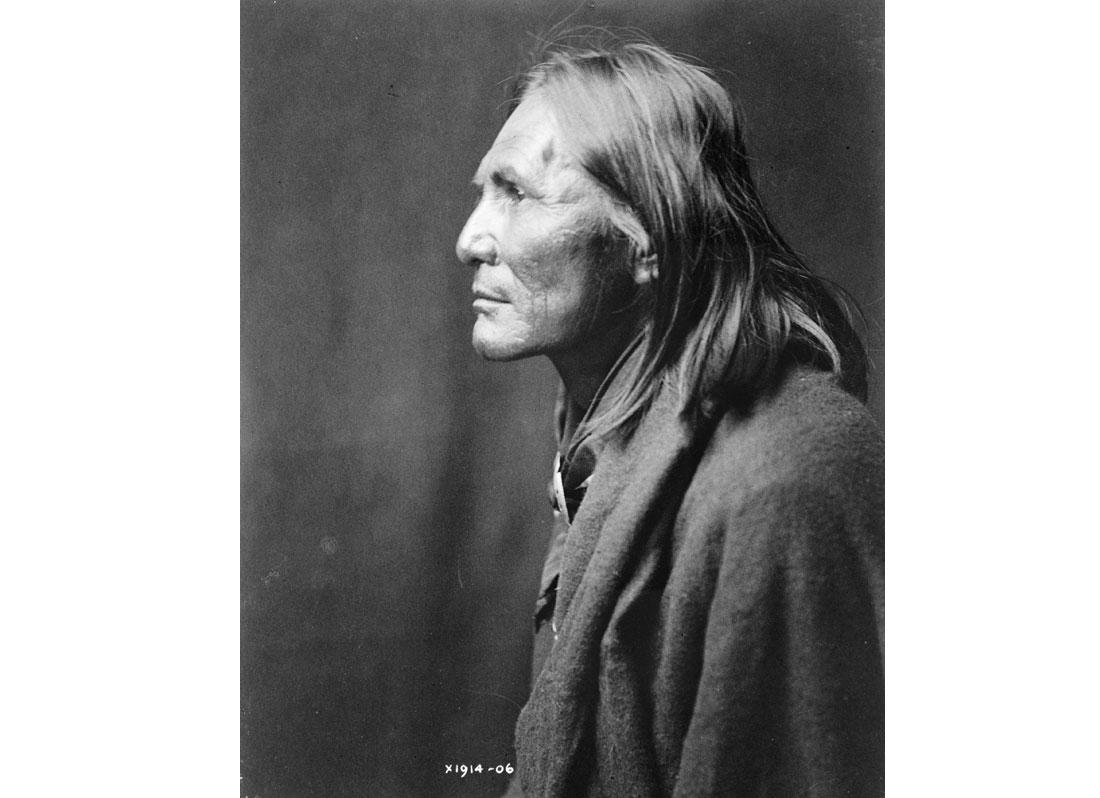

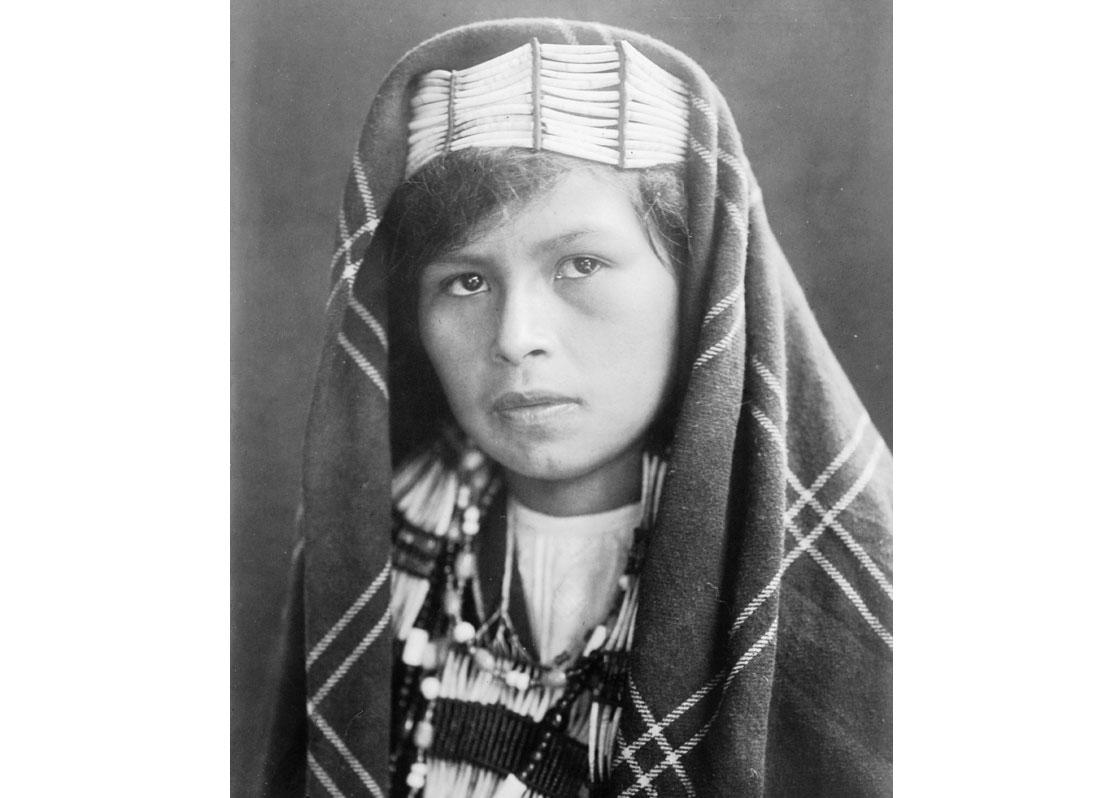

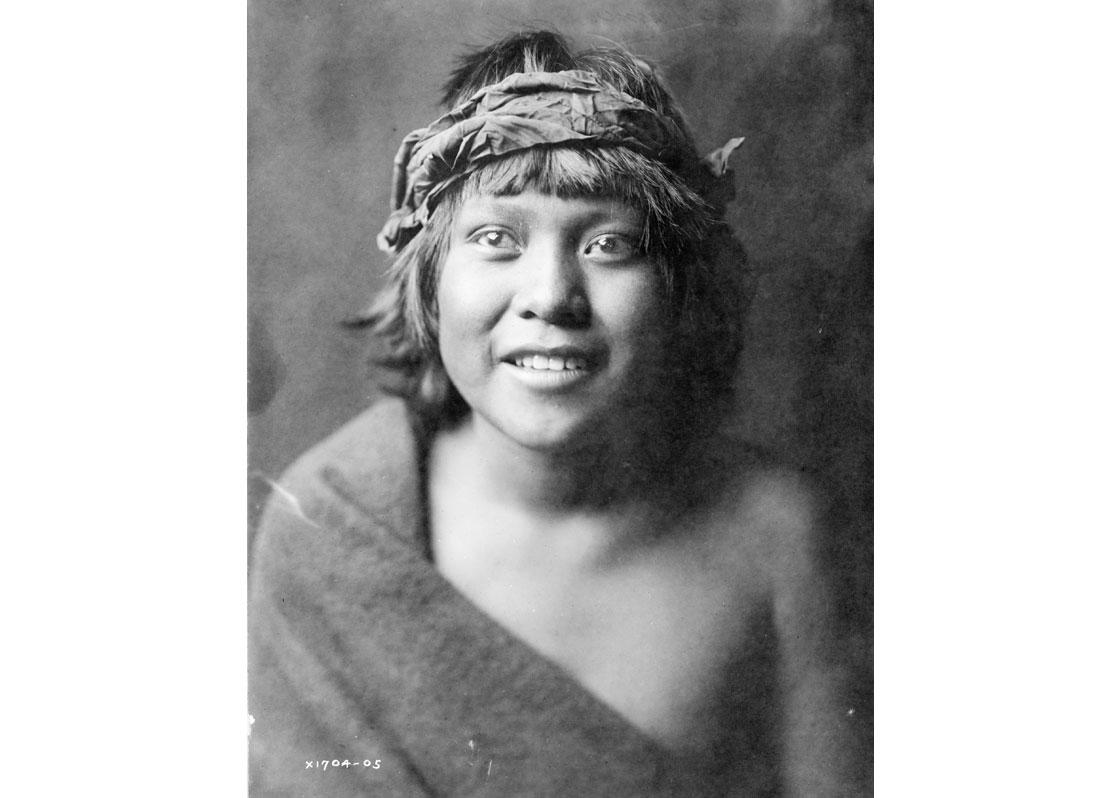

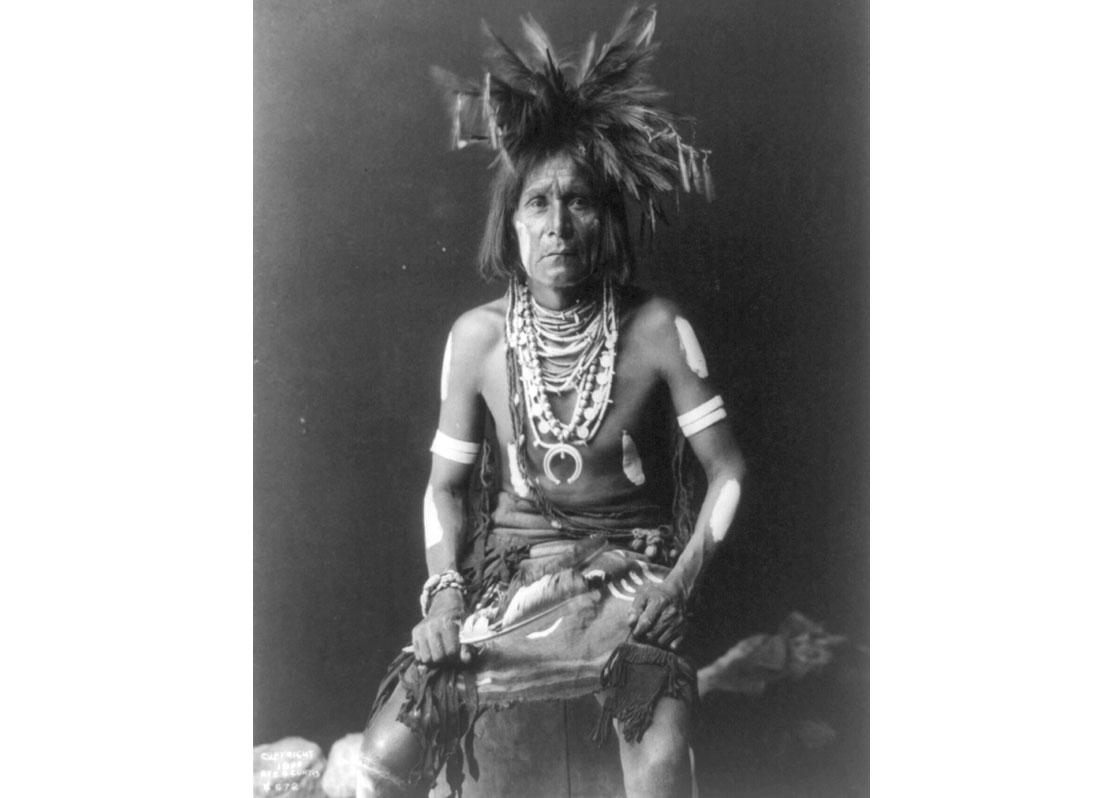

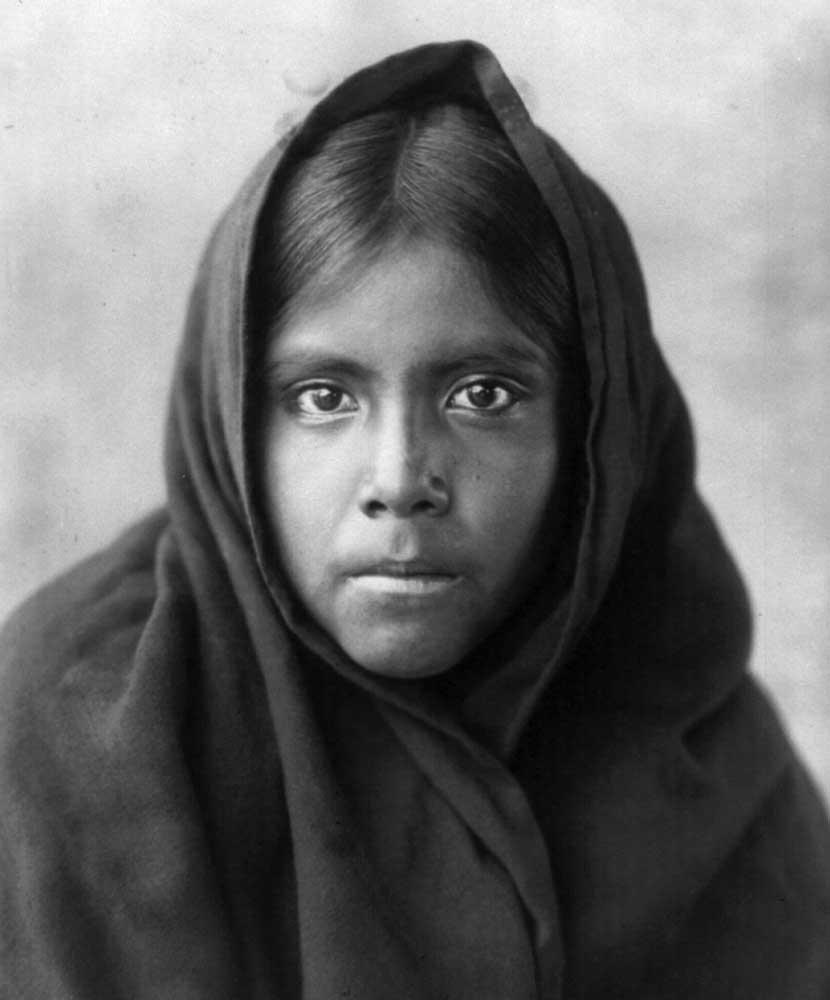

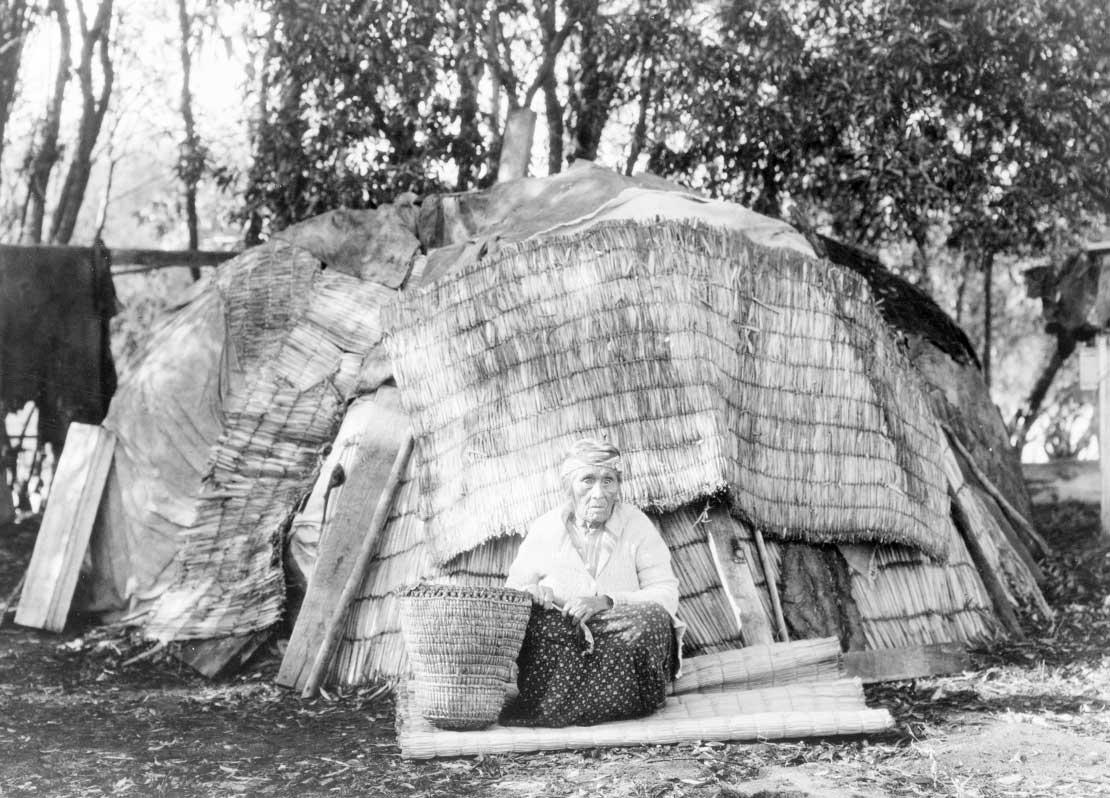

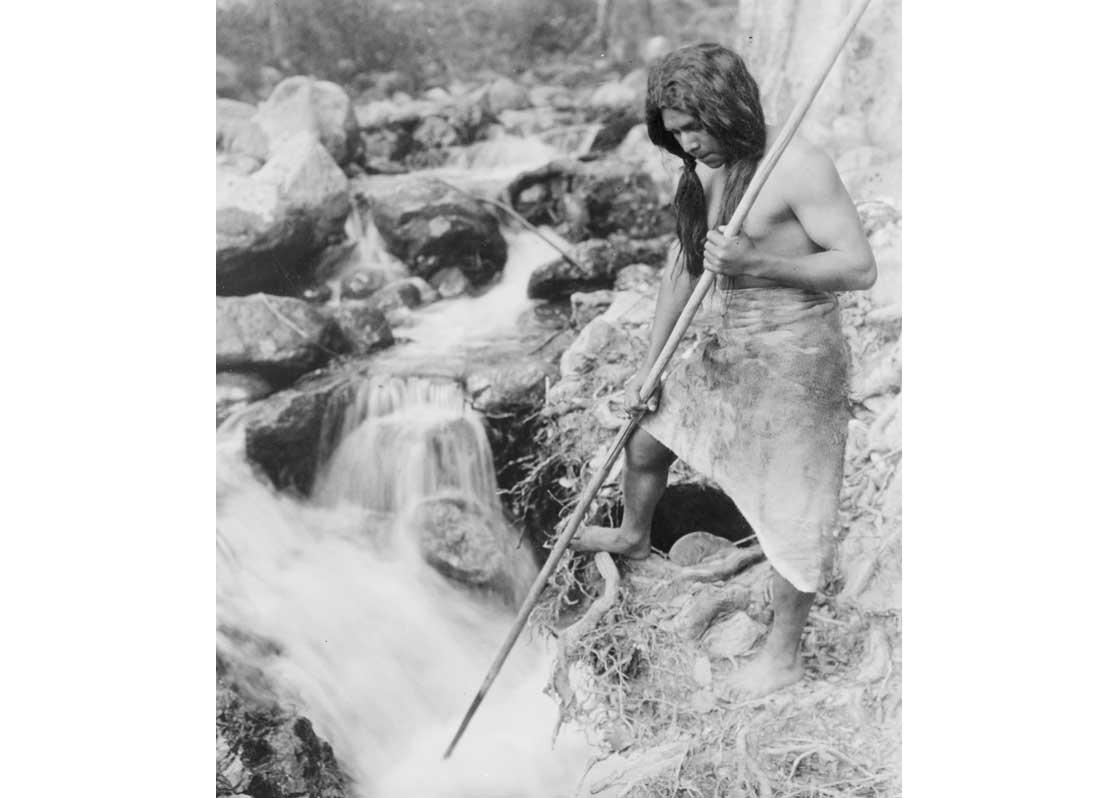

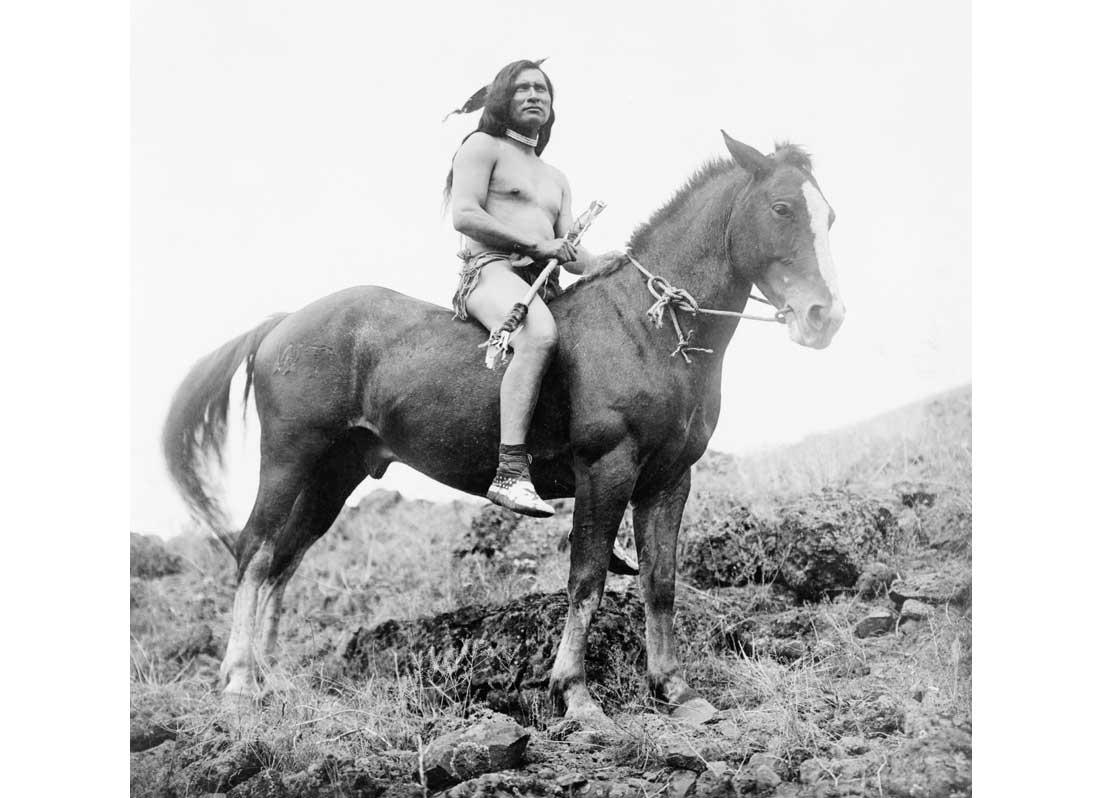

It is impossible to conceive of the photographic history of the American West without Edward Curtis’s The North American Indian, his massive project to document the life and culture of eighty Native American peoples published in twenty volumes between 1907 and 1930. Curtis, who by the 1890s was Seattle’s premier portrait photographer, began photographing the Coast Salish peoples of the Puget Sound in 1895. He made and sold views of Mount Rainier before serving as a photographer on railroad titan Edward Harriman’s privately funded expedition to Alaska in 1899.

The expedition was a who’s who of turn-of-the-century natural science, including anthropologist George Bird Grinnell, an expert on Plains cultures. It yielded more than 5,000 photographs, from which Harriman published a two-volume souvenir book featuring 253 photographs by Curtis and other expedition members. It was Grinnell who introduced Curtis to field work. Following the expedition, Grinnell invited him to a Piegan reservation in Montana to photograph a Sun Dance ceremony; Curtis subsequently made several trips to reservations in the Southwest in the early 1900s. Curtis believed, as did many early anthropologists, that the world’s “traditional” and “primitive” cultures would disappear as they were inevitably assimilated by more “civilized” ones. Likely influenced by the place of photography in early anthropological field work, by 1904 Curtis had embarked on his project to create a comprehensive record of indigenous peoples and cultures before they vanished.

At the same time, Curtis’s studio portraiture caught the eye of President Theodore Roosevelt, who commissioned him to photograph his family. With a letter from the president, this eventually allowed him to pitch his project to J. P. Morgan in 1906. Morgan funded it with $15,000 annually for five years (the equivalent of more than $350,000 annually in today’s dollars). The first volume of The North American Indian was published in 1907. Each volume combined text with photogravures, accompanied by a portfolio of large, unmounted photogravure plates. There were other projects as well: illustrated lectures, popular books, even a musicale at Carnegie Hall in 1911.