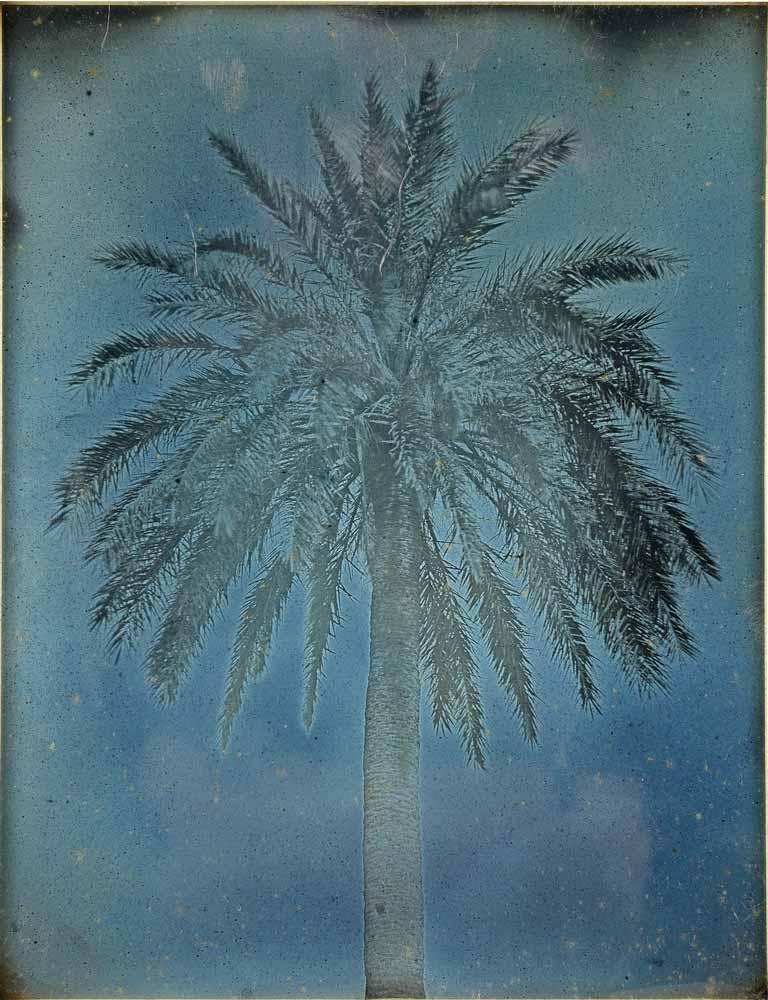

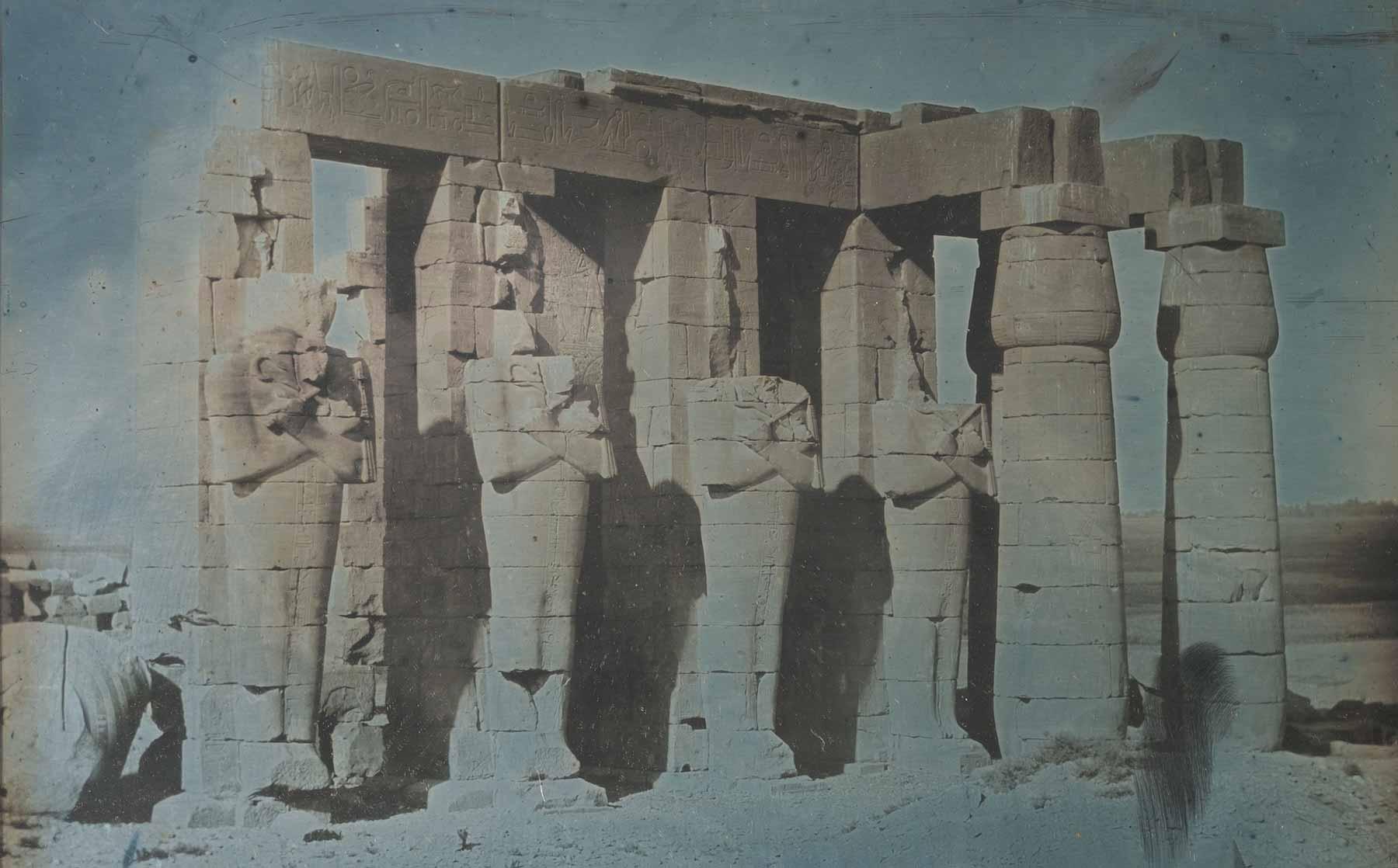

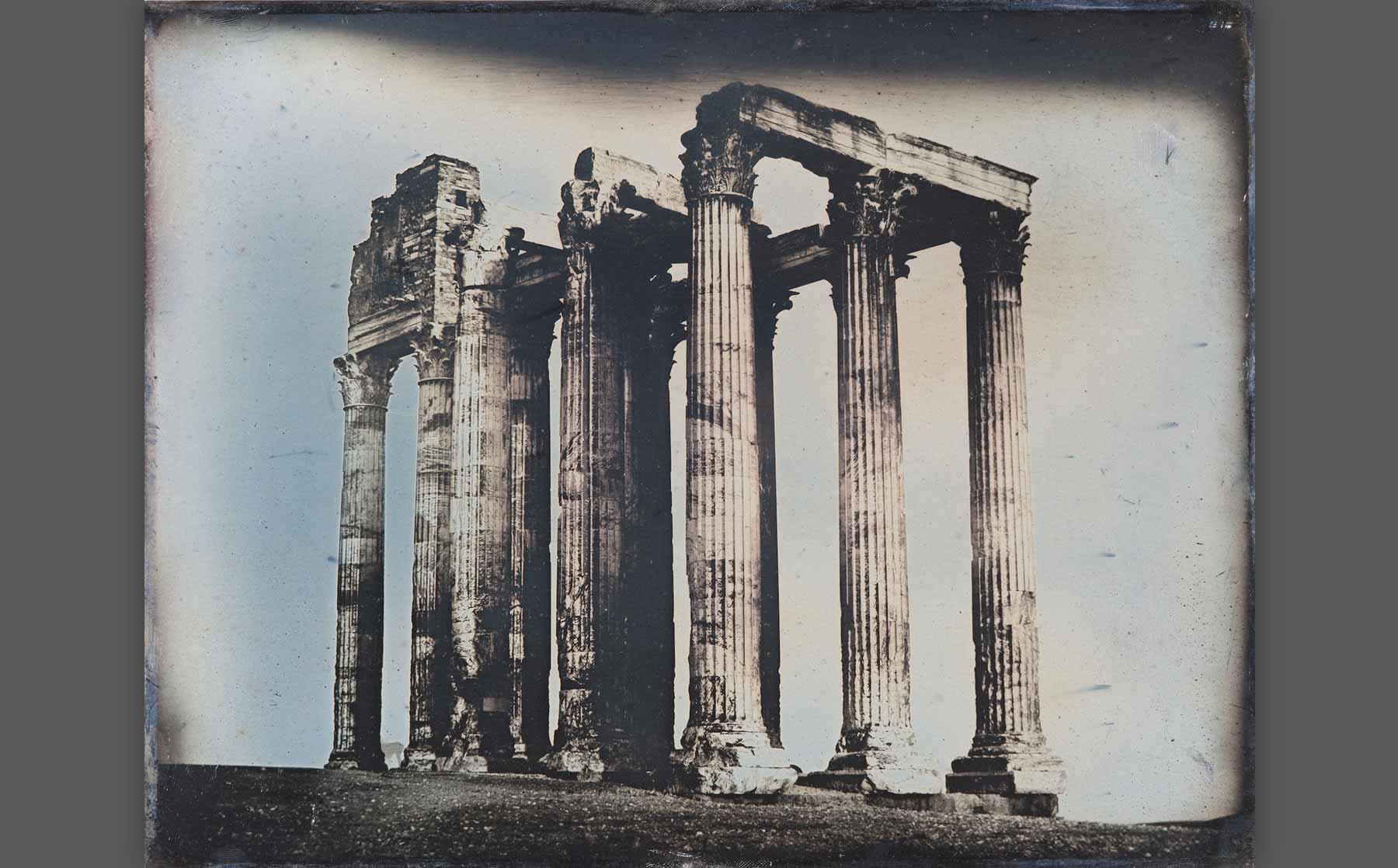

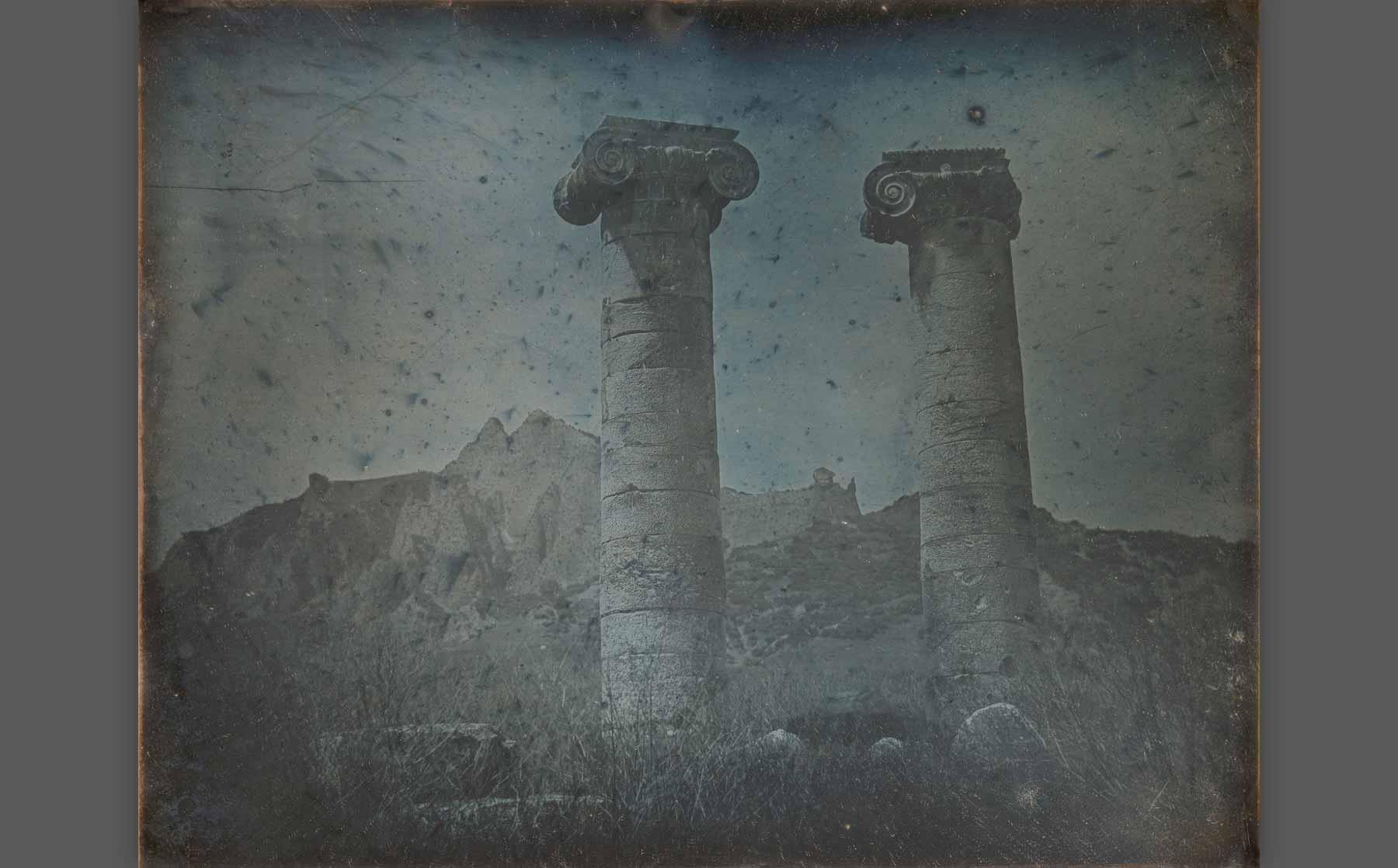

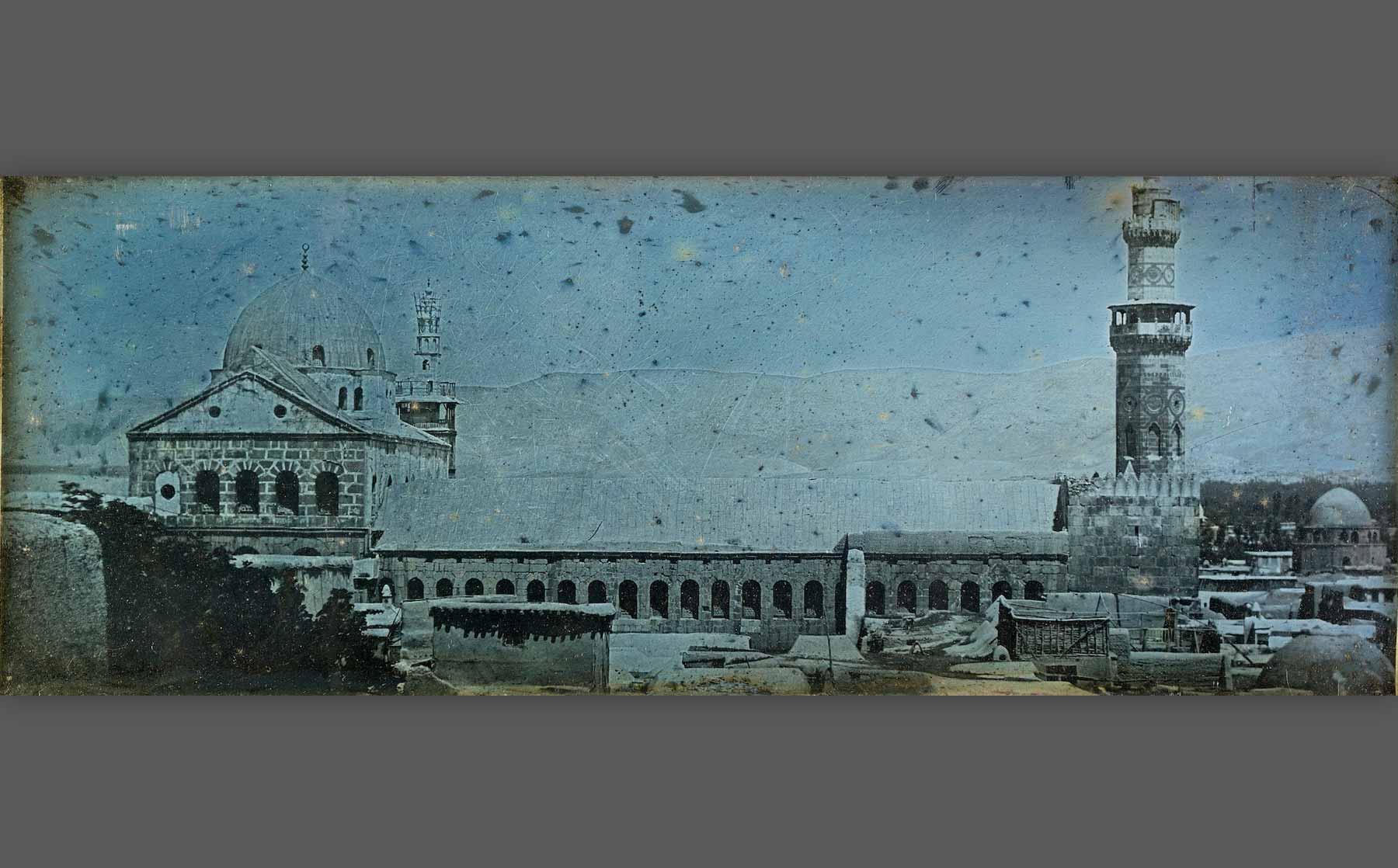

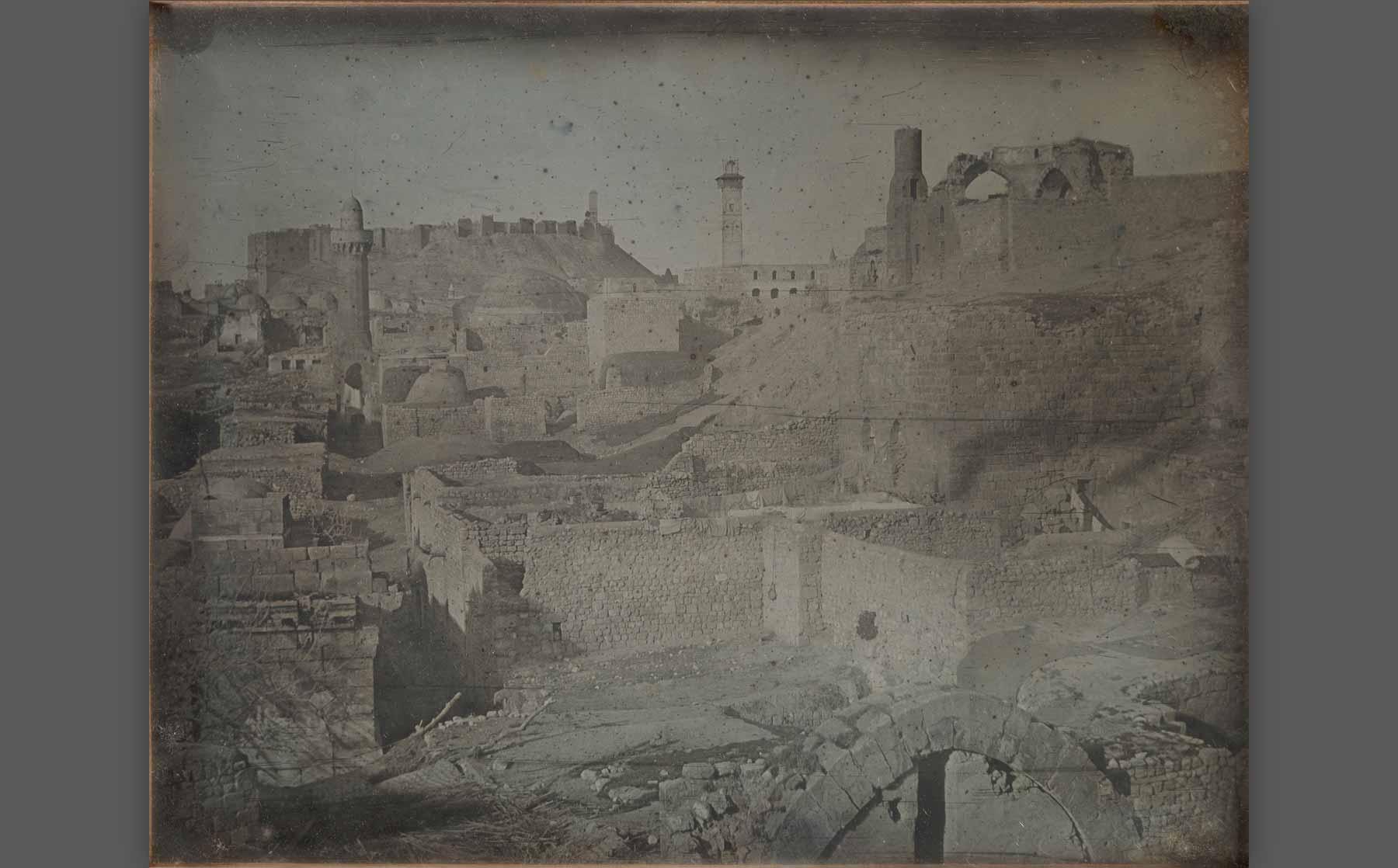

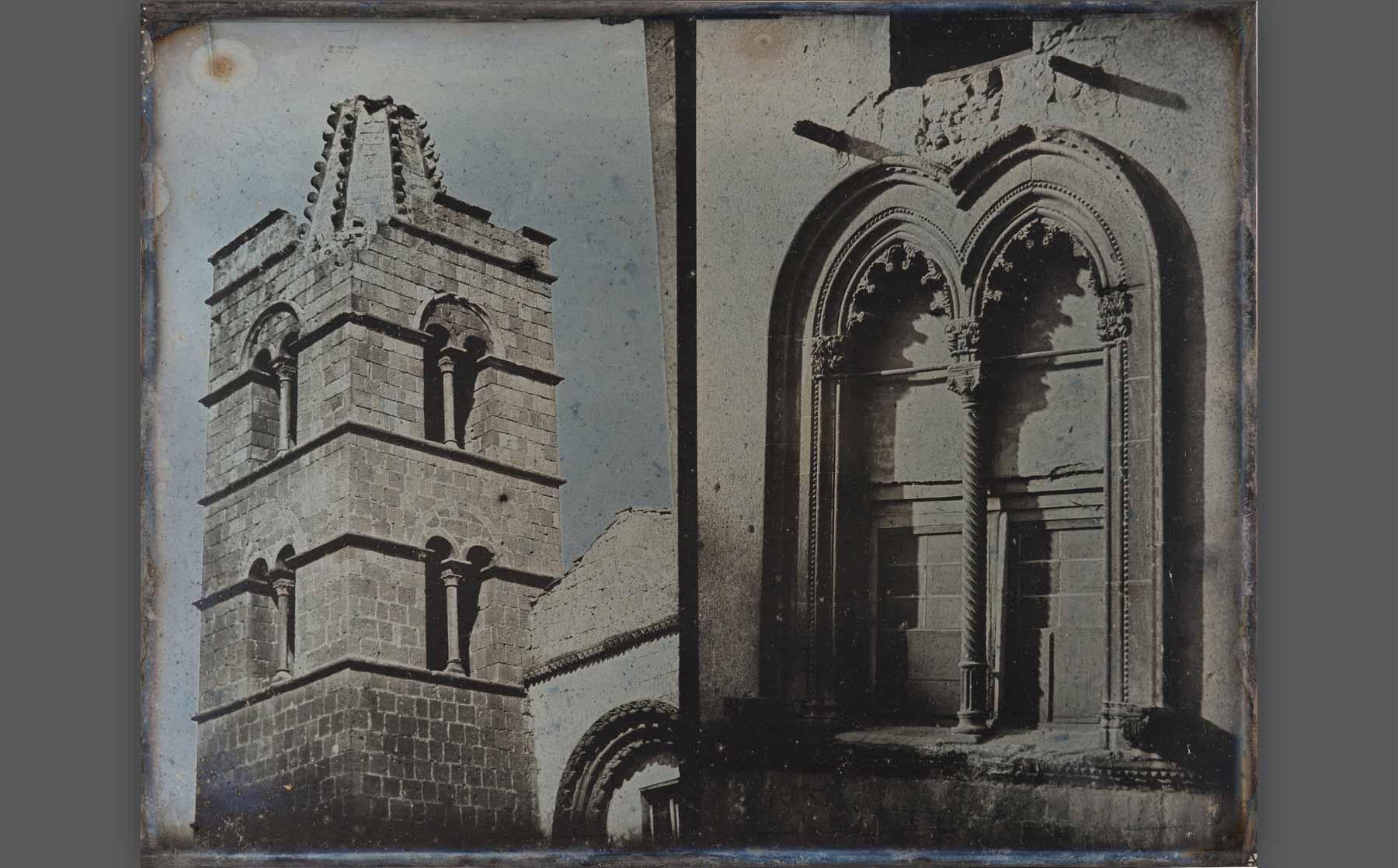

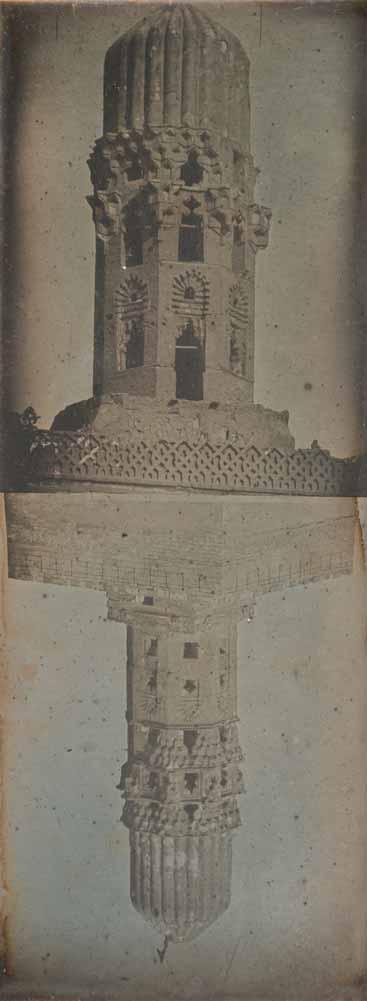

Between 1842 and 1845, Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey lugged his cumbersome camera equipment from his home in Langres, France, to the Eastern Mediterranean. The wealthy Frenchman had studied fine art in Paris before discovering photography after Louis Daguerre’s 1839 introduction of the daguerreotype. Girault had his own take on the new medium: fitting multiple exposures on a single oversized plate. In this way he took vertical panoramas of columns and minarets in Italy and Egypt, and horizontal vistas of Greece and Jerusalem. He later cut the plates apart into individual photographs. In Rome, for instance, he photographed a vertical shot of all 98 feet of Trajan's Column, then scaled the interior spiral staircase to capture from the top a sprawling panorama of the city with the Colosseum at its center.

He created hundreds of photographic images on silvered copper plates, many the first such documentation of these sites. Today, they offer glimpses of places now altered, like the Acropolis before the Byzantine, Frankish, and Ottoman structures were torn down after Greek independence, and Pompey’s Column in Alexandria marred with graffiti that was later removed. Others are now destroyed, such as portions of the ancient city of Aleppo, Syria. Despite the importance and innovation of this work, Girault’s legacy has long been obscure.

“Die hard photo historians, and a handful of curators, knew about him, but in terms of widespread exposure, he just wasn’t on the radar until the end of the twentieth century,” said Stephen C. Pinson, curator in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Photographs.