Leaf through any current Parisian guidebook and you’ll undoubtedly find Les Deux Plateaux (1986), contemporary artist Daniel Buren’s installation of black and white columns in the Palais-Royal courtyard. For many, the striped sculptures are a sightseeing stopover en route to the main cultural attraction across the street—the Musée du Louvre.

Travel guides of the eighteenth century, on the other hand, would have recommended the opposite itinerary. Then, the Palais-Royal was the ultimate tourist destination, famous for its galleries displaying a distinguished art collection that was publicly viewable (highly atypical at the time). One such book, Description historique de la ville de Paris (1765), described it as “the most interesting and the richest that exists in the world, not even excepting the king’s collection.”

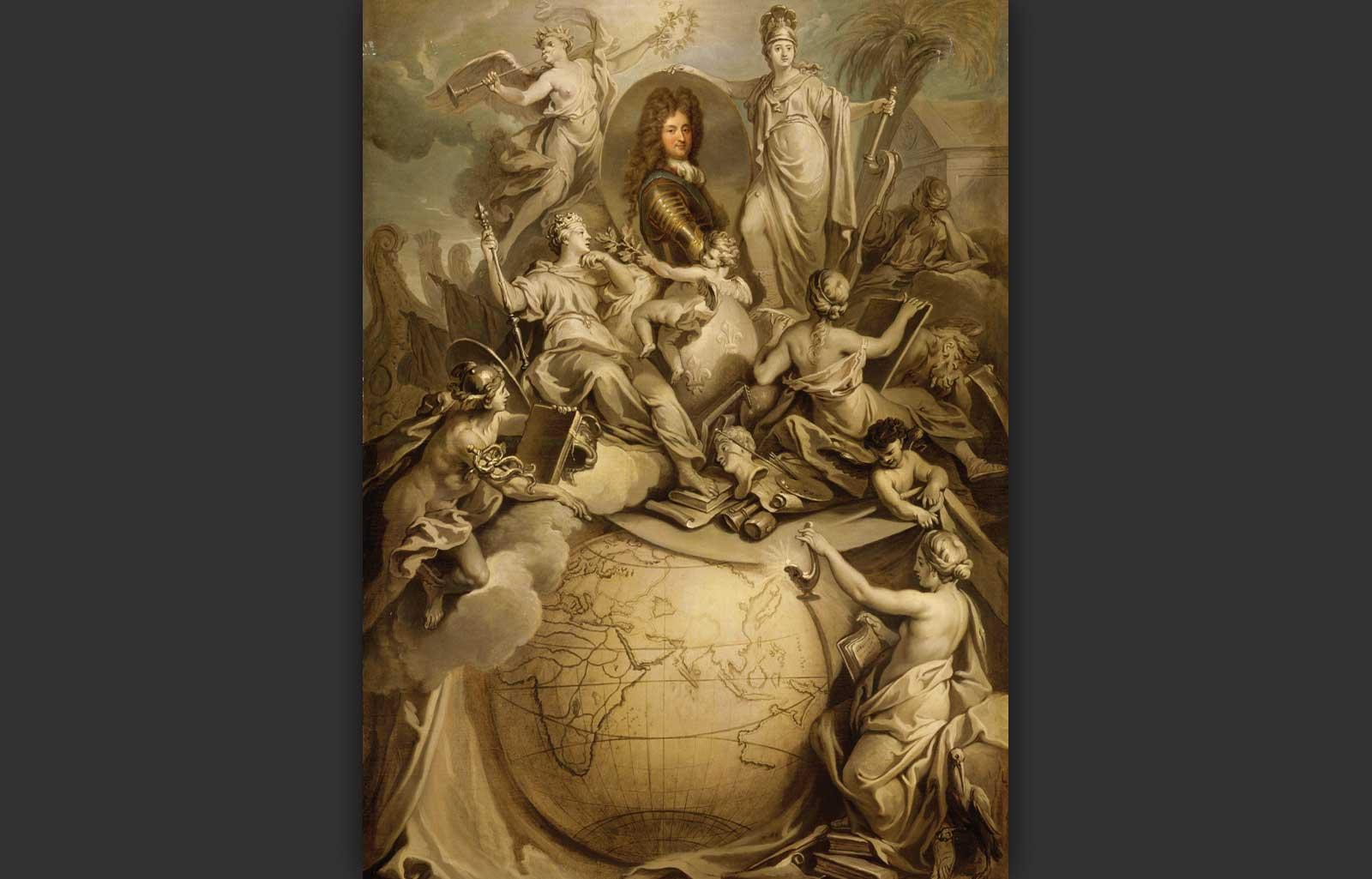

In four sunlit galleries overlooking the Palais-Royal gardens hung the personal collection of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, who acted as French regent for eight years between 1715 and 1723 while a young Louis XV matured before taking the throne. When the duke assumed his new role as interim king, he demonstrated his power through an extravagant presentation of his trove of masterpieces, welcoming any well-heeled guest to see it for themselves.

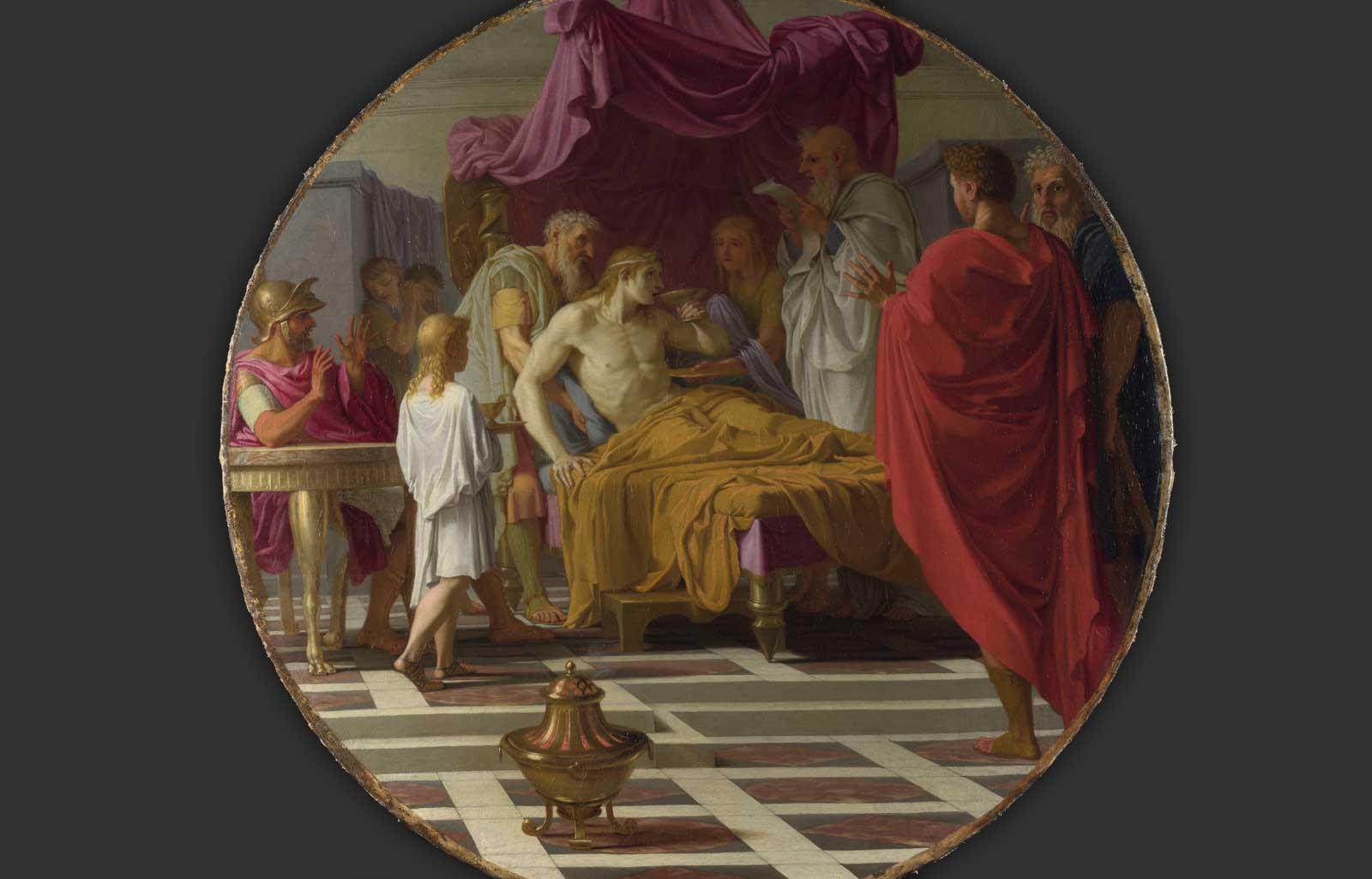

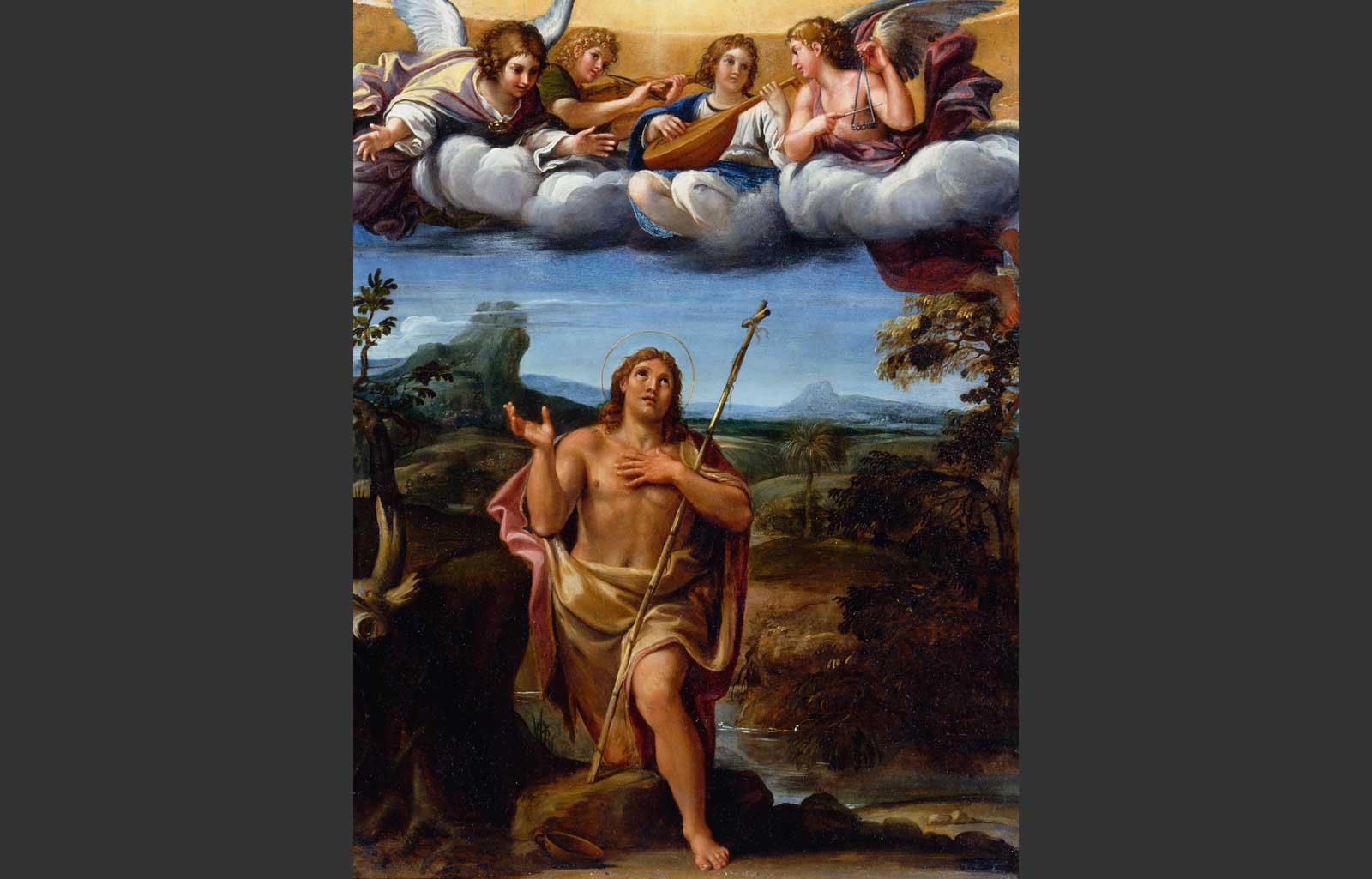

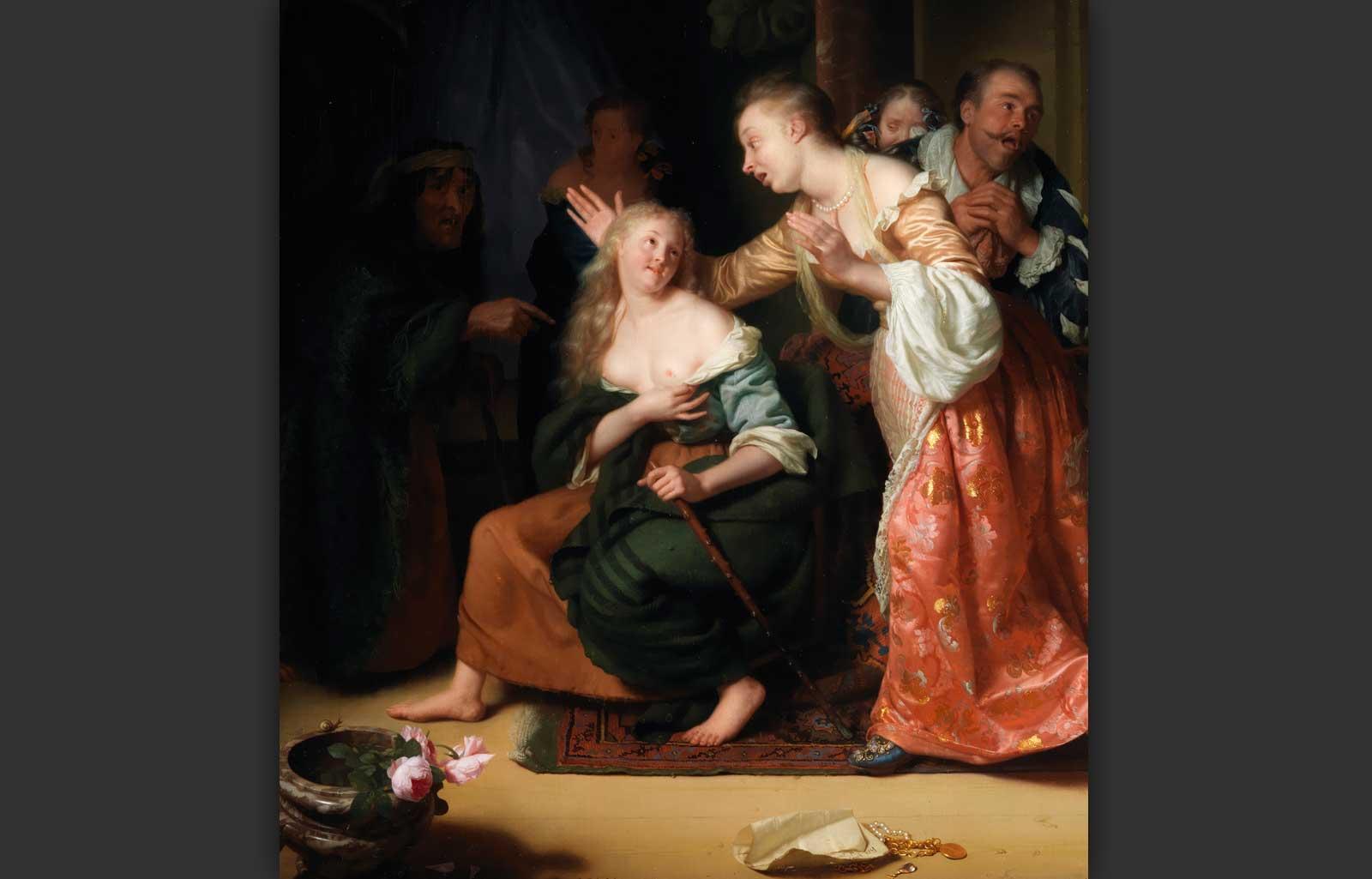

His impressive collection numbered 772 paintings; included were 29 Titians, 19 Veroneses, and ten Tintorettos (the largest grouping of these Venetian masters owned by any individual in history). He also had six Rembrandts, 12 Poussins and works by canonical giants such as Raphael, Correggio, Dürer, Rubens and Van Dyck.