That chain of events surely happened, but pinpointing O’Keeffe’s genesis at that particular moment ignores her arduous journey learning to translate the real-life objects she observed into a sensuously abstract language of shapes and forms. “There’s nothing less real than realism,” O’Keeffe is often quoted as saying, but how she got there is a skipped-over part of her story. That chapter began far removed from New York and Stieglitz (her future husband), in the historic and mountainous surroundings of Charlottesville, Virginia.

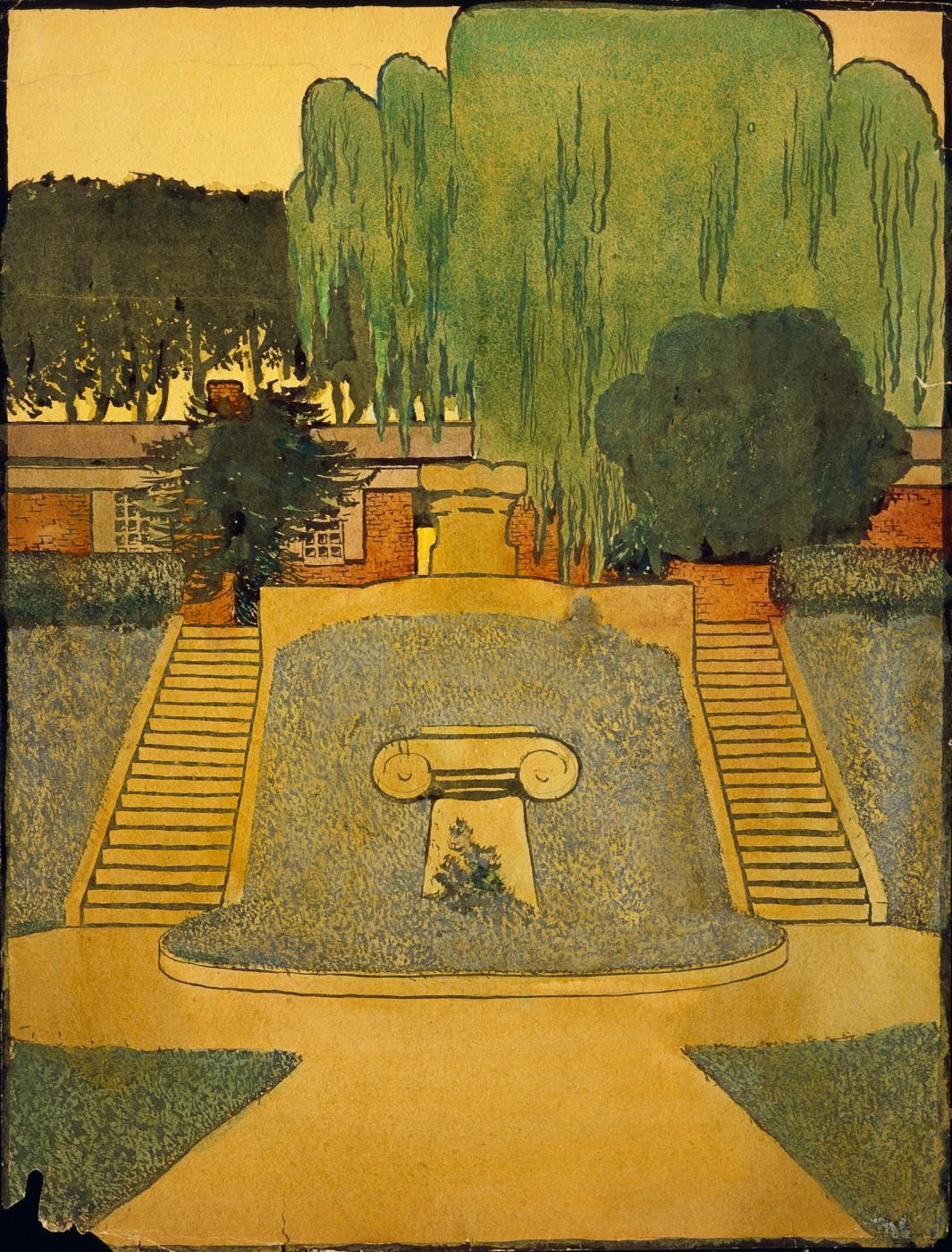

A new exhibition at the Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia–where O’Keeffe spent five summers between 1912 and 1916, first as a student and then as a teaching assistant–hopes to claim its campus as a major starting point in the painter’s modernist trajectory. Unexpected O’Keeffe: The Virginia Watercolors and Later Paintings displays–for the first time outside of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe–watercolors and oil paintings created during her summers there that ultimately culminated in the abstract charcoal drawings that Stieglitz so admired.

“We have an opportunity here to begin to tell that story,” says Elizabeth Hutton Turner, a modern art professor at the University of Virginia and co-organizer of the current exhibition. “We picked this new beginning.”

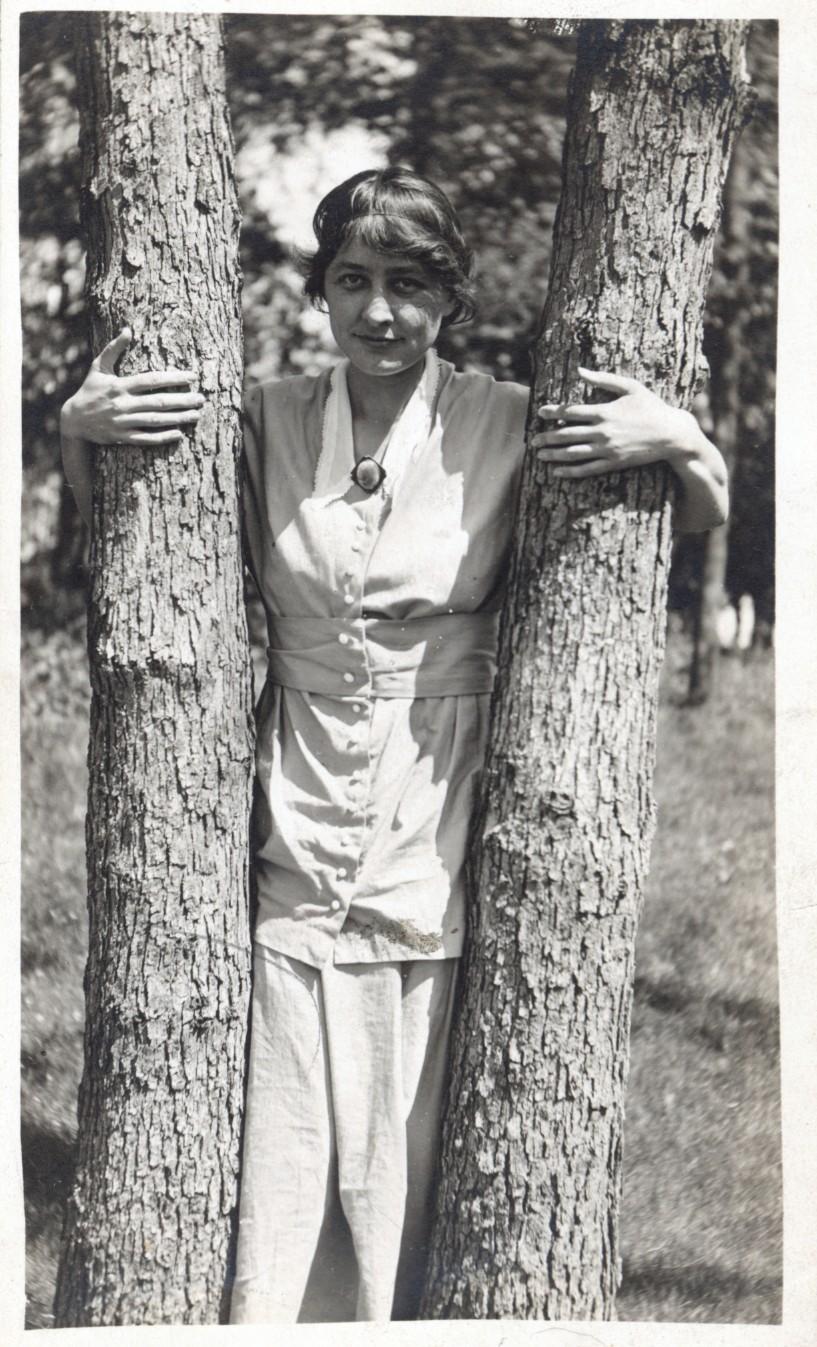

Family first brought a 24-year-old O’Keeffe to Charlottesville. After moving several times throughout Georgia’s childhood, the O’Keeffe family settled in a brick Victorian home at 1212 Wertland Street, which was a short walk from the University of Virginia. They made ends meet by renting rooms to local students (and the house, which still stands and has since been divided into apartments, continues to be a popular student rental).