When we think of the quintessential Renaissance Man, the first two names that naturally come to mind are Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) and Michelangelo (1475-1564). The former had interests—actually areas of excellence—that included drawing, painting, sculpting, mathematics, music, and engineering, while Michelangelo was known as a sculptor, painter, architect, and poet. However, one generation prior, Andrea del Verrocchio (1435-1488) successfully embodied this ideal as a goldsmith, sculptor, painter, musician, draftsman while also maintaining an active workshop that trained the likes of Lorenzo di Credi, Pietro Perugino, and Leonardo da Vinci.

A 2019 exhibition that traveled from Florence's Palazzo Strozzi to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. was the first monographic exhibition of this (once) overlooked master.

“The idea of the exhibit sprang from the fact that both me and co-curator Andrea de Marchi think that Verrocchio is an artist of utmost importance, on a par with Giotto, Donatello, Raffaello and Michelangelo,” co-curator professor Francesco Caglioti told Art & Object. “We think he invented the style [that would become the high-Renaissance style]. He had a universal reach, anticipating the universality of Leonardo, who, surely, had his own proclivity, but was largely encouraged by his master.”

Masters, in art history, tend to be merely remembered for their most notable students. The phrase that “those who can’t do, teach” has an interesting connotation in art history. In fact, the vast majority of the most eminent painters and sculptors were taught or had an apprenticeship led by masters who gave them the necessary tools, but never managed to get notoriety or distinction themselves. Francesco Squarcione (1395-1468), for example, was a tailor and an ancient-art enthusiast, who collected Grecian and Roman sculptures and trained more than 130 painters. His most famous student? Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) who was taught to study Roman sculptures by his master.

Likewise, Simone Peterzano (1535-1599), a mannerist painter known for his penchant for monumentality, is mainly remembered for being the one who taught a young Caravaggio (1571-1610). More outrageously, when, in the late 1800s, the Salon dictated what artists and painters were deemed worthy, Fernand Cormon (1845-1924) established a successful atelier where he would coach aspiring artists to create paintings that would be deemed a fit for the Salon: of course, now we mainly remember him because of his more wayward students who went against his teachings, namely Vincent van Gogh and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

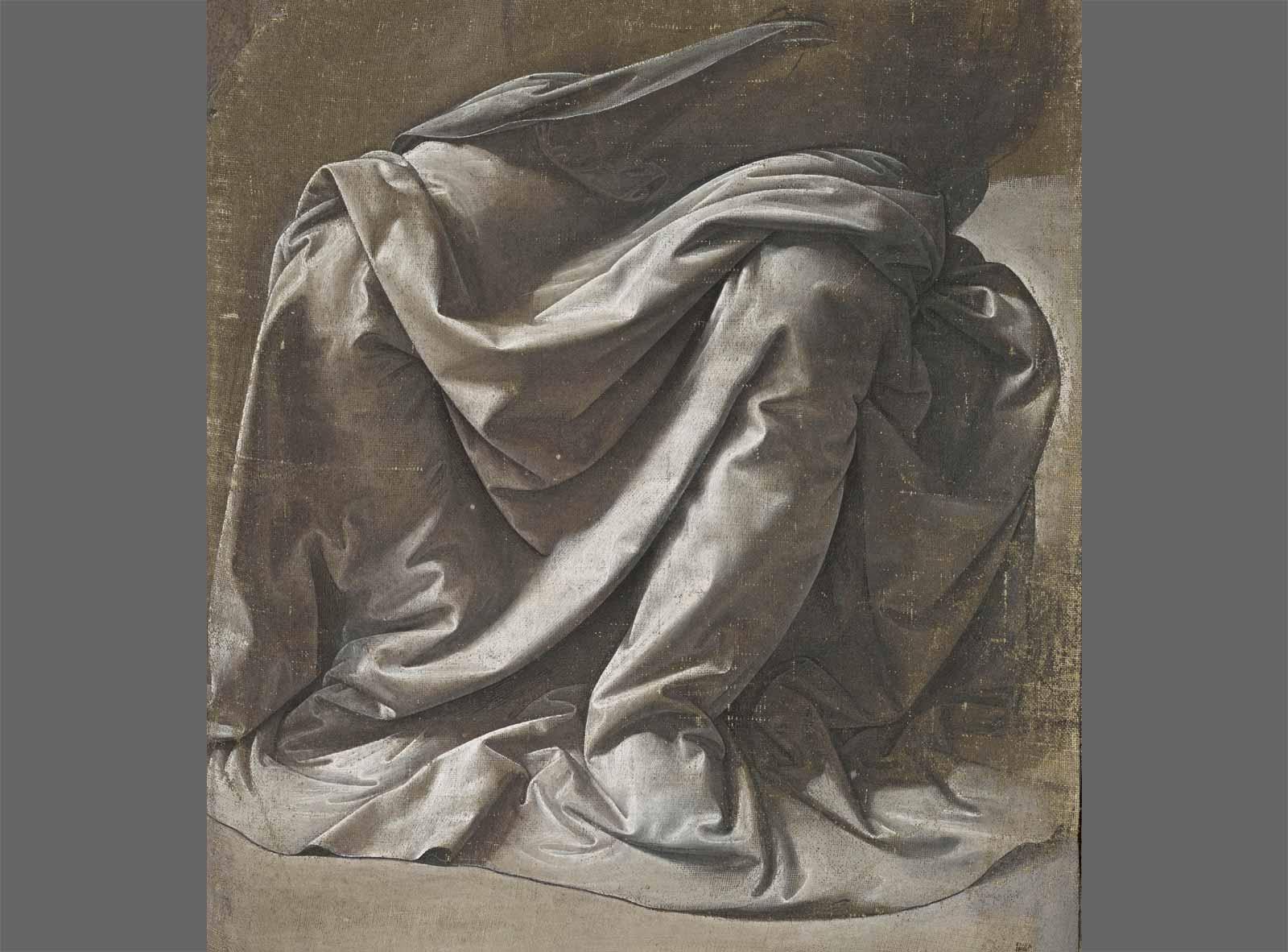

Contrary to the stereotype of teachers whose artistic skills were unremarkable and lacked innovation, Verrocchio is known for bringing about significant changes. In fact, he was, first and foremost, a great observer of nature. Up until the mid-1800s, artists had been striving to have art imitate nature in the closest possible manner. “[With Verrocchio,] nature is perfectly imitated, and he is the first artist who allows art to go beyond nature,” Caglioti explained. He also refined the imagery surrounding the Madonna with Child, and equaled the Flemish masters in the rendering of highlights, shadows, and translucent surfaces, such as jewels.