Dimensionism never became a fully-fledged or well-known artistic movement, but many of the artists who supported it are household names. They include Kandinsky, Marcel Duchamp, Alexander Calder, and Joan Miró, who were among the slew of famous artists who signed Hungarian poet Charles Sirató’s 1936 Dimensionist Manifesto. Proclaiming that literature, painting, and sculpture had entered a new age, Sirató and his contemporaries saw that art, like science, had made massive leaps forward, so far forward, in fact, that they had stepped out of the bounds of three dimensions and into four. These artists were moved by scientific advancements of the early 20th century, such as Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, to expand what art consisted of, and bring it into dialogue with larger concepts of space and time.

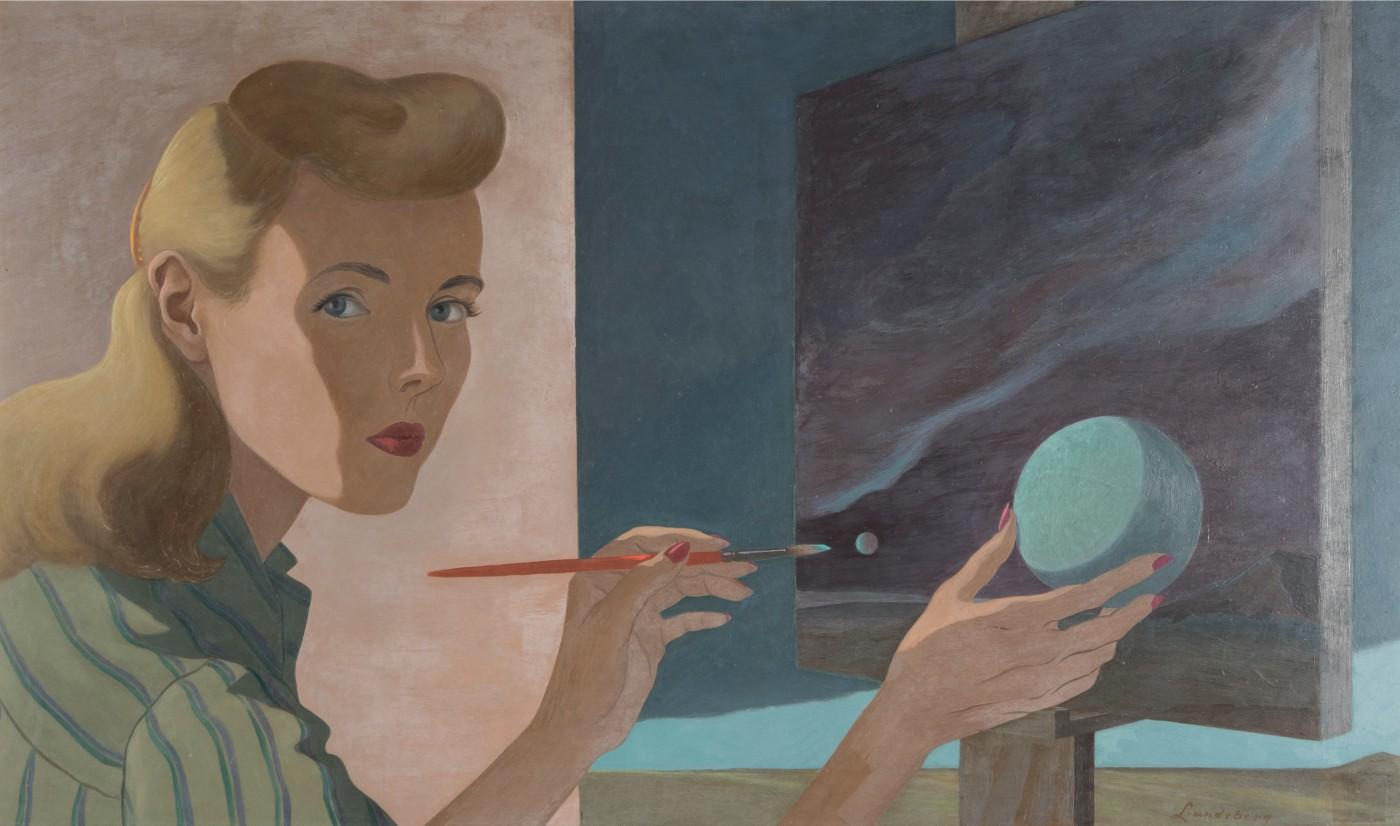

Helen Lundeberg, Self Portrait, 1944. Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey; Gift of The Lorser Feitelson and Helen Lundeberg Feitelson Arts Foundation.

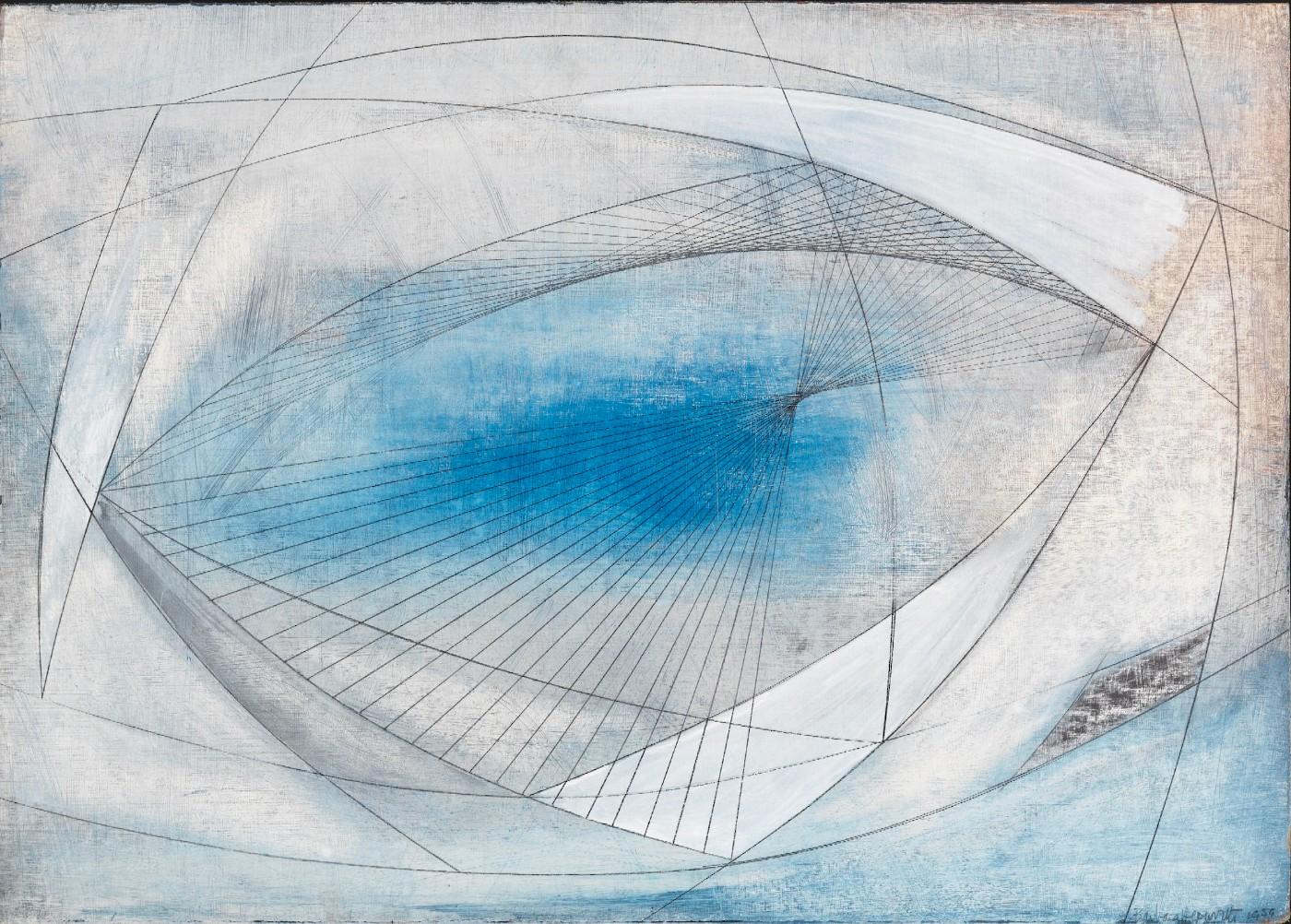

Joan Miró, Composition, 1937. University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; Gift of Julian J. and Joachim Jean Aberbach.

Barbara Hepworth, Project for Wood and Strings, Trezion II, 1959. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, Amherst, Massachusetts; Gift of Richard S. Zeisler (Class of 1937) (1960.1).

The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) explores how science and art inspired each other in Dimensionism: Modern Art in the Age of Einstein, the first exhibition to highlight the untold story of the Dimensionist Manifesto. Bringing together a range of modern, avant-garde works, Vanja Malloy, the Mead Art Museum’s curator of American art, connects the works through their ties to scientific developments of the era. Barbara Hepworth was inspired by the x-ray crystallographer J.D. Bernal, as seen in her striking 1959 painting Project for Wood and Strings, Trezion II. Miró’s images are often reminiscent of bioforms moving beneath the lens of a microscope, while the Picasso’s Cubism was both inspired by and inspired questions about how we perceive the world, seeming to answer Sirató’s call for “painting leaving the plane and entering space.”

Isamu Noguchi, Yellow Landscape, 1943 (partially reconstructed, 1995). The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York.

Meanwhile, works from Calder and Isamu Noguchi, like Yellow Landscape, 1943, clearly embody Sirató’s idea of “sculpture stepping out of closed, immobile forms.” In his Dimensionist Manifesto Sirató also predicted that “a completely new art form will develop: Cosmic Art. ...The human being, rather than regarding the art object from the exterior, becomes the center and five-sensed subject of the artwork, which operates within a closed and completely controlled cosmic space.“ Though Sirató’s description is vague, it certainly brings to mind performance and body art, forms of expression that were just being developed.

Herbert Matter, East Indian Dancer, Pravina, 1937. Stanford University Libraries. Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Dimensionism: Modern Art in the Age of Einstein is on view at BAMPFA through March 3, 2019. It will then move to the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College from March 28 to June 2, 2019.