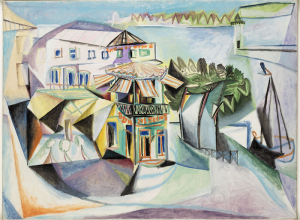

“It had a huge impact on my work,” says McClure. She studied Japanese paper making at the university. While there, she immersed herself in watching films from the video store, ranging from Ingmar Bergman’s brooding, psychologically penetrating films to Japanese classics like Ozu Yasuhiro’s Tokyo Story to the slapstick comedies of Jacques Tati.

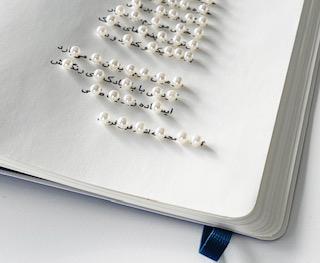

Fascinated by language, its connection with the visual, and the craft of paper making, she learned to speak fluent Japanese and found herself shocked by the many mistranslations she began to encounter, attributing them not only to linguistic mistakes but also to cultural misunderstandings.

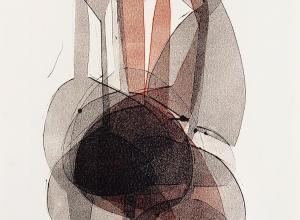

McClure maintains that it’s “the gray areas between cultures and languages” that most interest her and she addresses this subject specifically throughout her multifaceted work.