PL: What will you be doing in this new role with the Cleveland Cavaliers?

DA: This position of creative director for a team hadn’t really existed in the NBA. It’s a completely new position. Basically, I’m responsible for every outward facing thing that our team is doing, from the jerseys to everything you see on court. The job is storytelling, not only about our team—the Cavs and the Cavs history—but about Cleveland, too. We’re looking at all types of ways to tell that story. We’re obviously living in the unique moment of not having that many fans in the arena, but we’re looking forward to coming out of it. And, we’re especially looking forward to February 2022, when the NBA All-Star Game will be in Cleveland. It’s going to be huge for the team and the city, as well.

PL: While this position with the Cavs is new, collaboration with brands is something you’ve been successfully doing for years. What are some of your favorite collaborative projects and how do these opportunities inspire your own art and design practices?

DA: The collaborations have to make sense within my own universe. Some have been things that I liked in advance or was engaged with before the collaboration began. One of my favorites is an ongoing project and collaboration with Porsche. I’ve been a fan of Porsche cars since I was a teenager, when I made drawings of them. To be able to engage with that history, to be able to create artworks as vehicles with them has been a lifetime dream, a big goal. However, all of the collaborations that I’ve done have functioned like that in some way. One of the big draws for me—in addition to the joy of being able to enter these brands’ universes—is relishing the reach that they have. Artists—and the art world in general—exist in a somewhat close-knit universe. Not everyone is part of that world, nor do they feel comfortable going to galleries and museums, or they don’t live in a city where art is so prominent. The collaborations I’ve done have brought my work to audiences that are not traditional art audiences, and that’s been beneficial for me and my work.

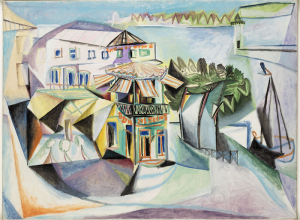

PL: Your recent collaboration with Dior Homme was huge, from the design of clothing and accessories to the tent and stage for the Paris runway show last year. Did it start with one idea that grew into many different pieces?

DA: I had an in-depth collaboration with Dior Homme creative director Kim Jones. It involved heavy amounts of research at the Dior archive in Paris. He and I spent a lot of time looking at pieces that had been produced in the past, whether it was during the original Christian Dior era or from the more recent John Galliano era. I’m obviously not a clothing designer, so I worked closely with Kim, which was more like me throwing him ideas. A lot of it was about distilling down ideas, revisiting the origins of the house, and then introducing new materials and new techniques into the mix. It was a fascinating project for me in every way.

PL: You may not be a clothing designer, but you are a partner in the design firm Snarkitecture and you recently launched a line of furniture under the name Objects for Living. What types of challenges do these pursuits represent to you as an artist?