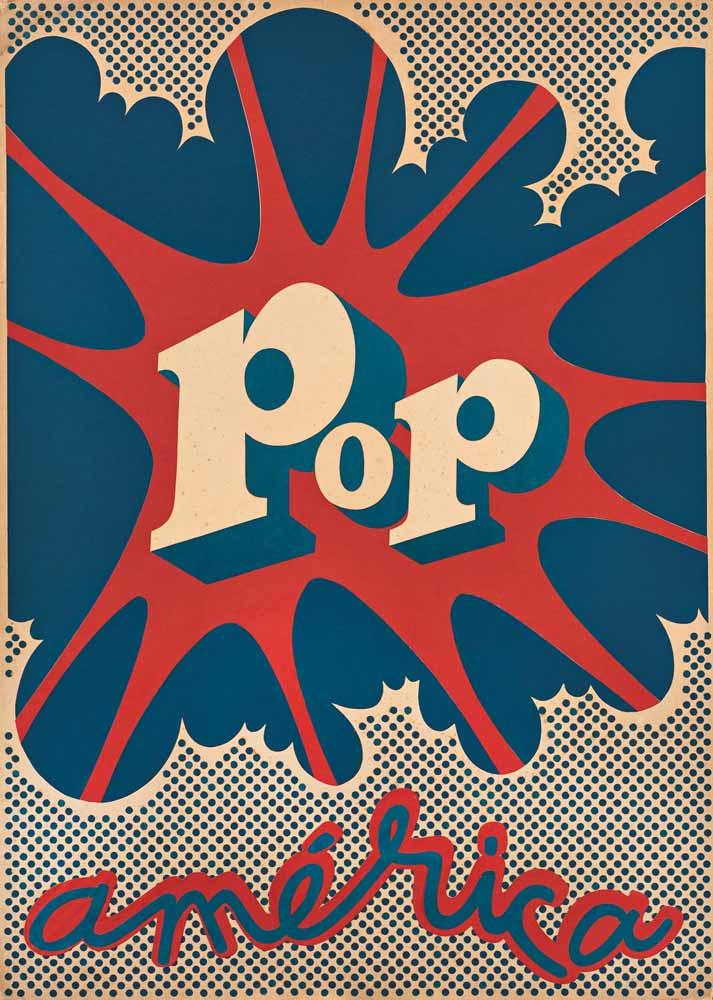

Only in recent years have these artists received much (or any) institutional and international recognition. In 2015, the traveling exhibition International Pop and Tate Modern’s The World Goes Pop presented global surveys of Pop beyond canonized white male artists (Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, et al.). This summer, the New Museum restaged Argentinian artist Marta Minujín’s La Menesunda, a high-sensory, pop-surrealist installation that engages with and exploits the frenzy of mass media. The first US museum retrospective of Colombian painter Beatriz González, who also mined mass media in her practice, is currently traveling. And Pop América, an expanded view of Pop Art in the Americas—and which takes its name from Rivera-Scott’s collage—is wrapping up its own year-long journey.

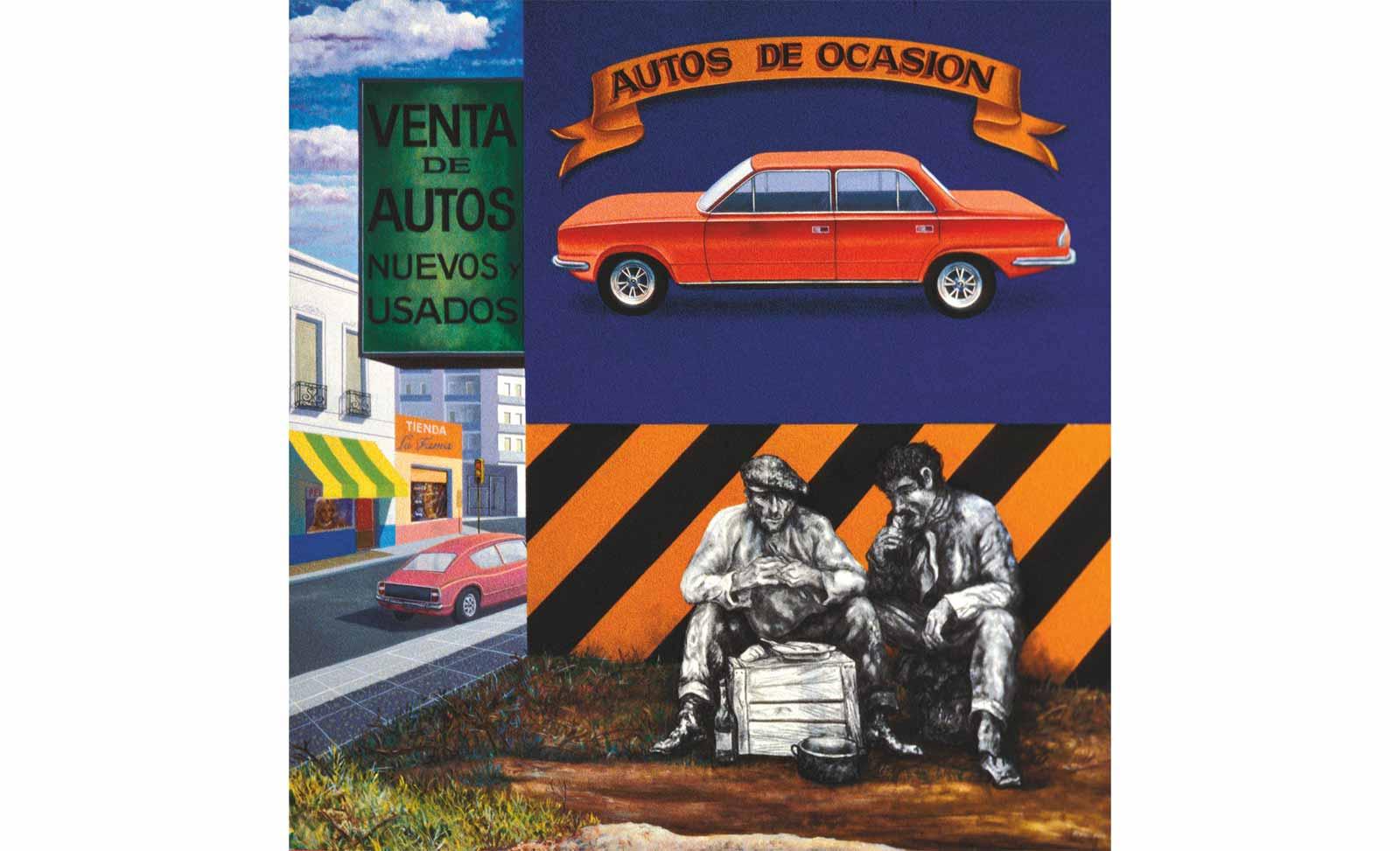

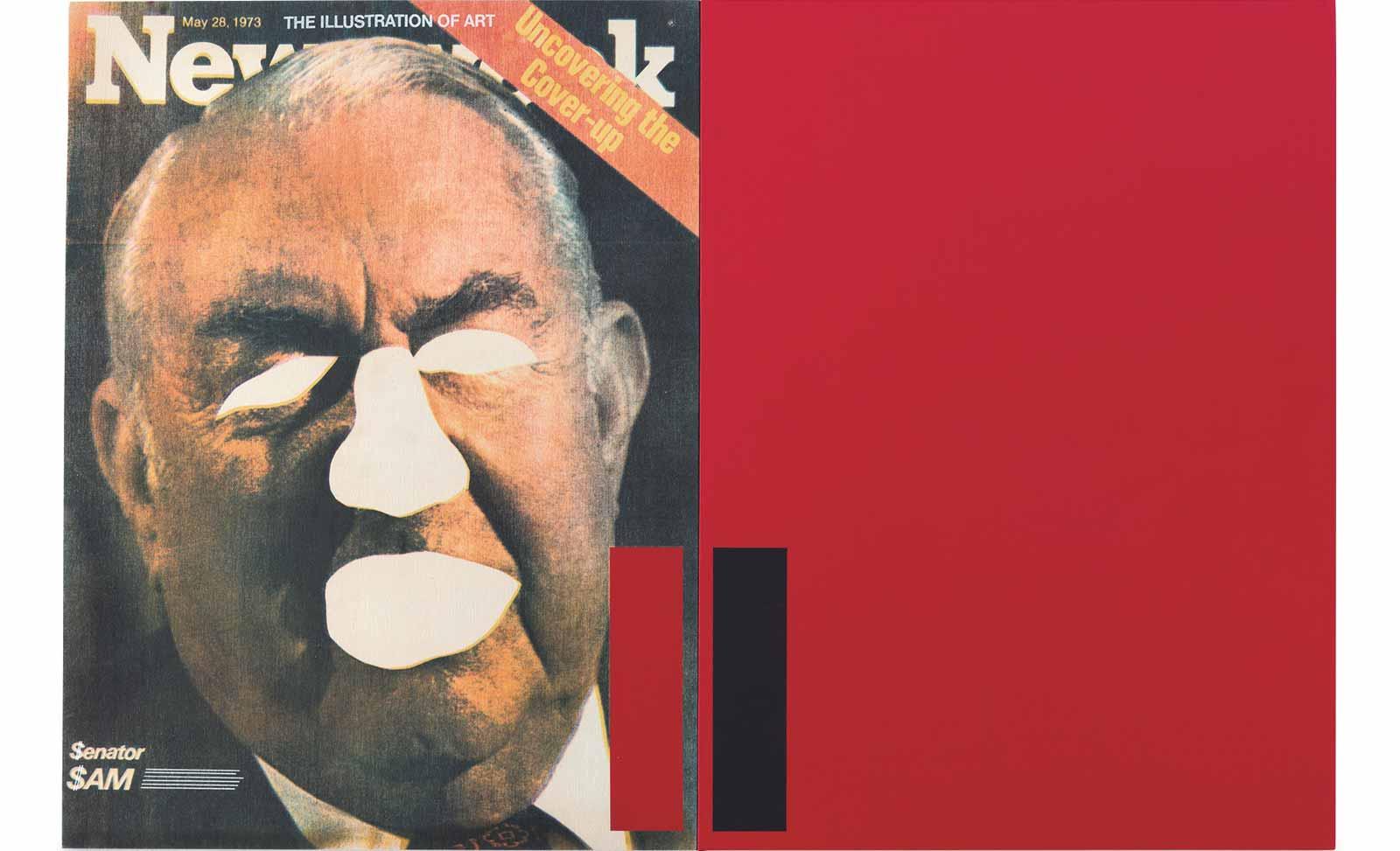

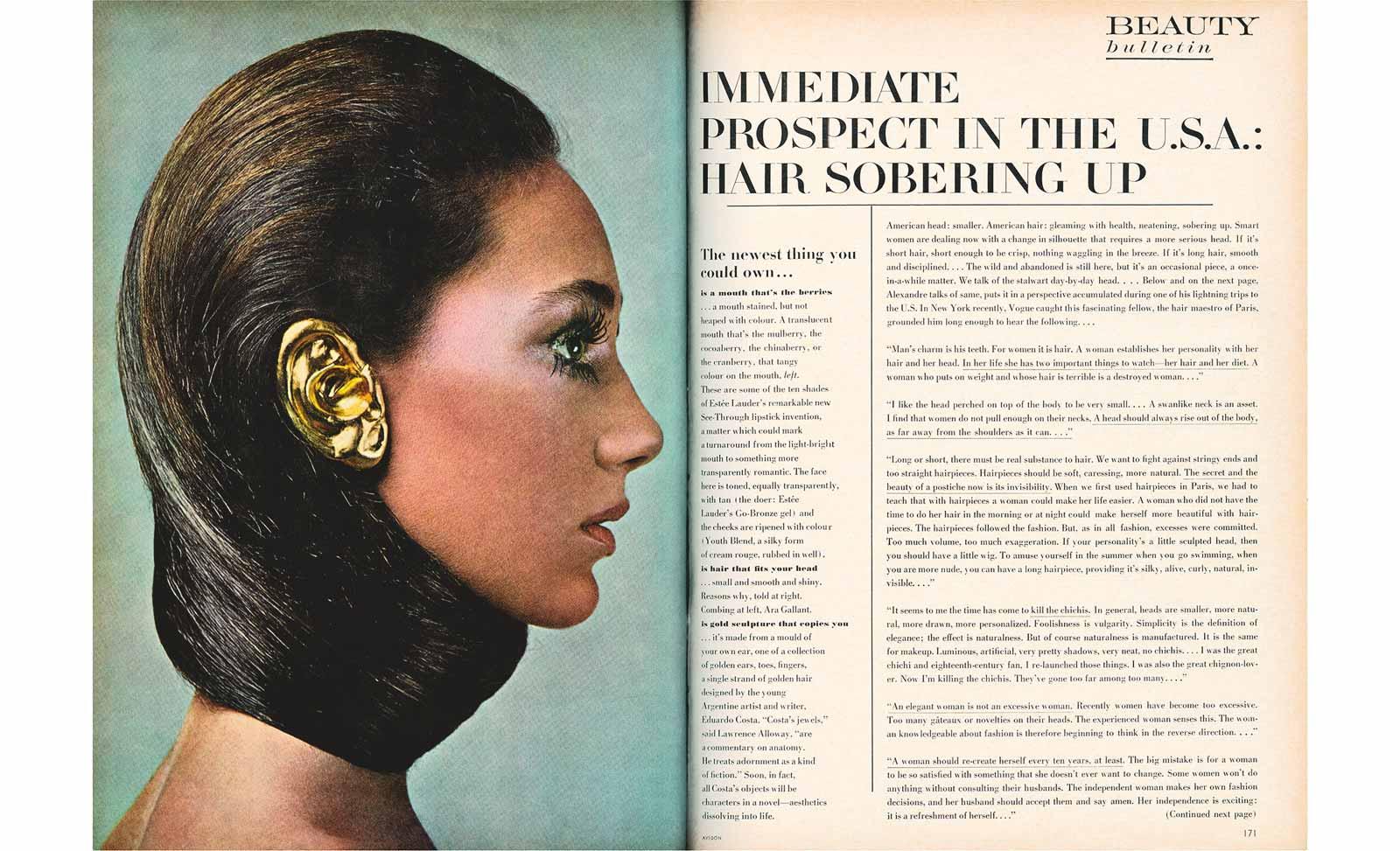

Now at the Block Museum at Northwestern University, Pop América examines the decade from 1965 to 1975, a period of political turmoil and social dissent in Latin America. As student protests erupted in Mexico City; military regimes controlled Brazil, Chile, and Argentina; and American imperialism stirred debates over the meaning and costs of freedom, many artists turned to the language of Pop to express themselves. Like Rivera-Scott, they used bright colors, flattened imagery, and other cues from mass-circulated, commodified pictures to spread radical messages under repressive conditions. This was a period exploding with visuals—a world of signs and icons of both abundance and catastrophe—and artists quickly mined the political potential of this new media, with all its anarchic sensibilities.

“A lot of these artists were looking at the commercial world as a source of inspiration,” the Block Museum’s academic curator Corinne Granof told Art & Object. “They were looking at popular culture, mass culture, advertising, and really bringing it into their art, using it as a source, or critiquing the consumer world.” Yet, she added, “there is definitely a political edge to many of the works. We’re sparked to challenge the perceived political neutrality of Pop.”

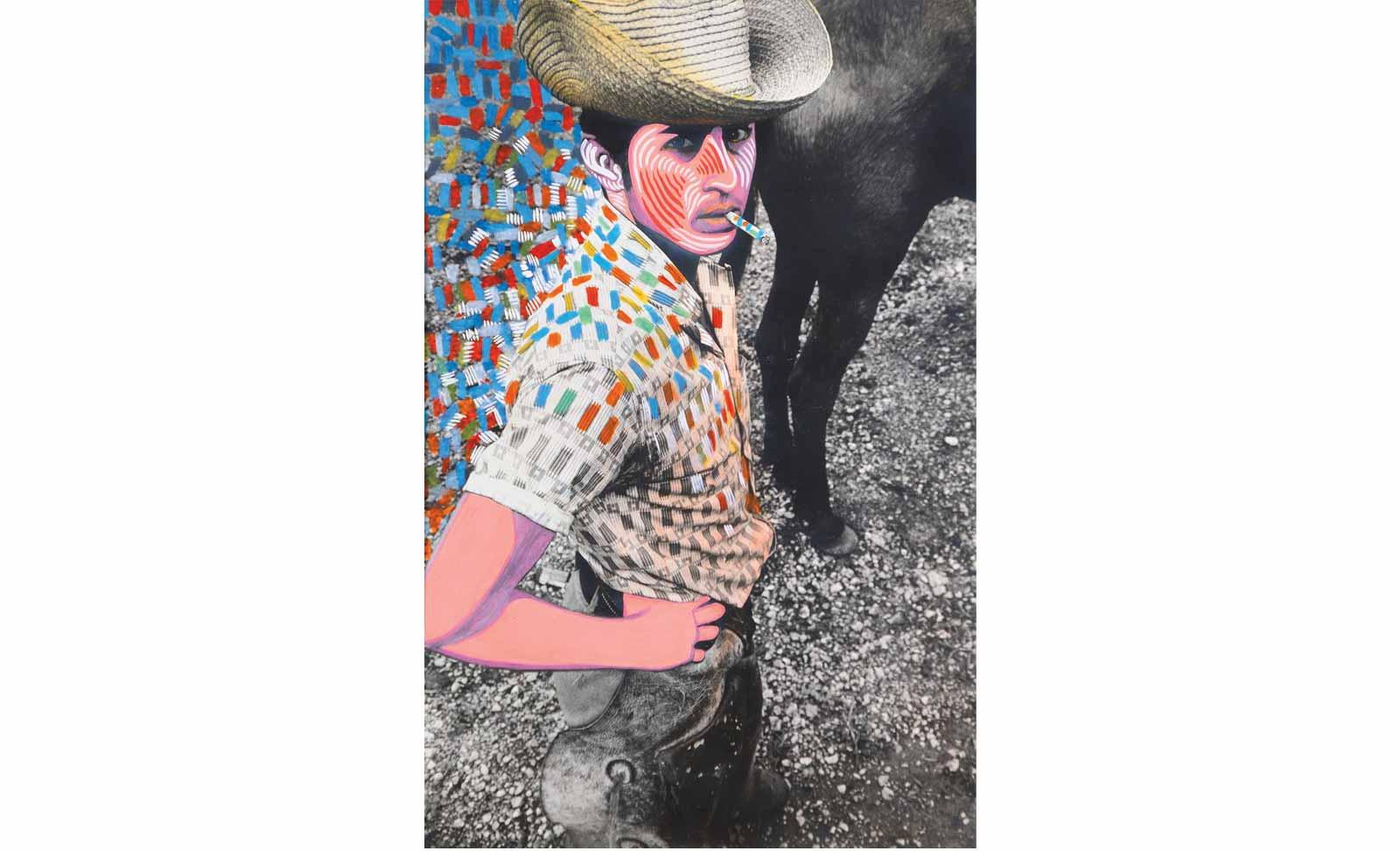

When artists grasped the power of media and its swift impact on society in terms of communication and consumerism, the realization signaled a general turn away from Abstract Expressionism and its indirectness. Cuban artist Raúl Martínez, who trained in abstract painting and worked as a commercial artist, began painting graphic, eye-catching portraits in the ‘60s that celebrated a distinct Cuban identity. These depicted national figures like the Cuban revolutionary José Martí, often in serially repeated, high-contrast imagery or framed in grids (not unlike, more famously, Warhol’s works). But others paid tribute to unsung heroes, like rural workers and athletes. El Vaquero (1969) is a photograph of a cowboy that Martínez painted over in vibrant colors, transforming the anonymous youth into a celebratory and vivacious icon.