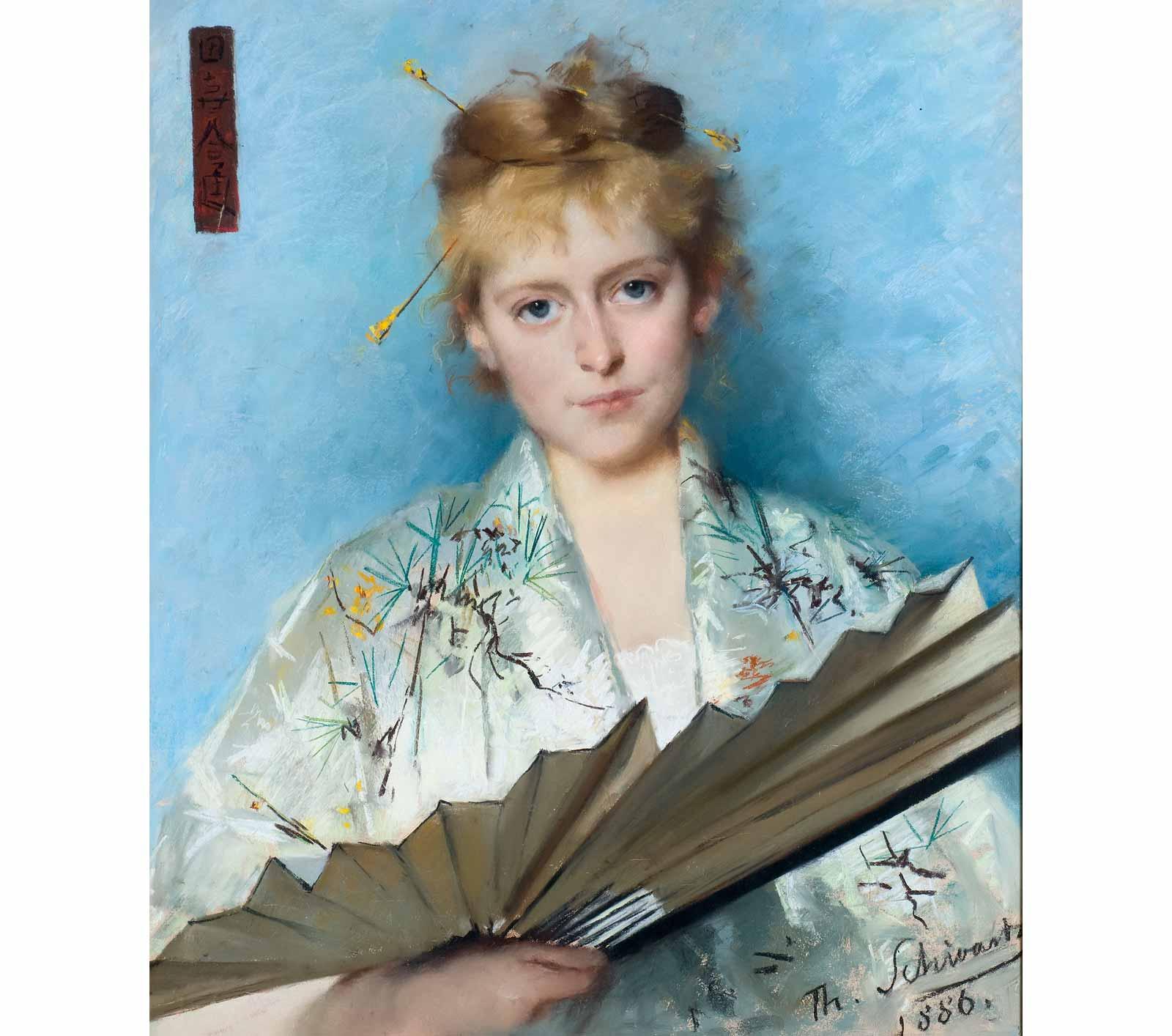

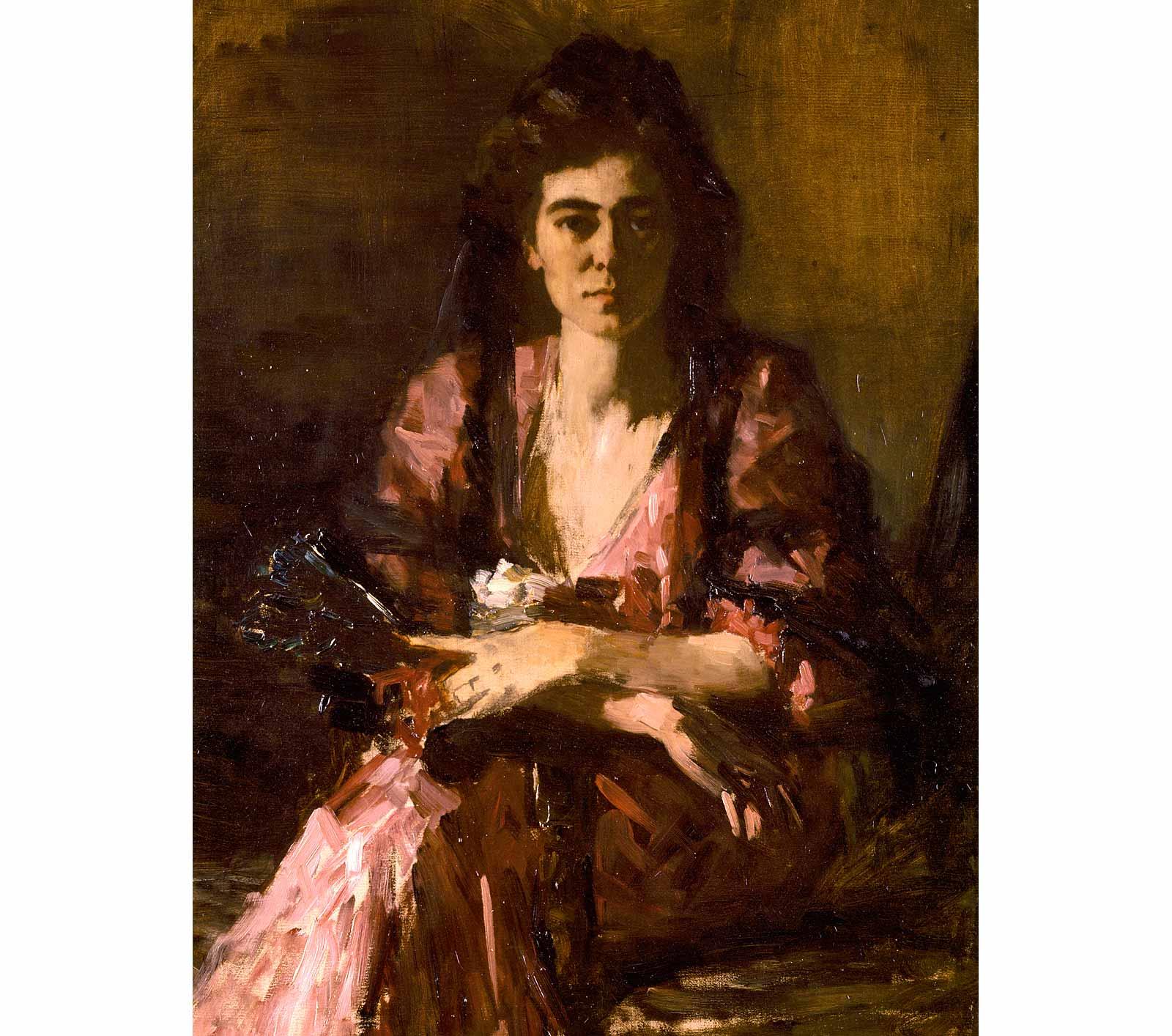

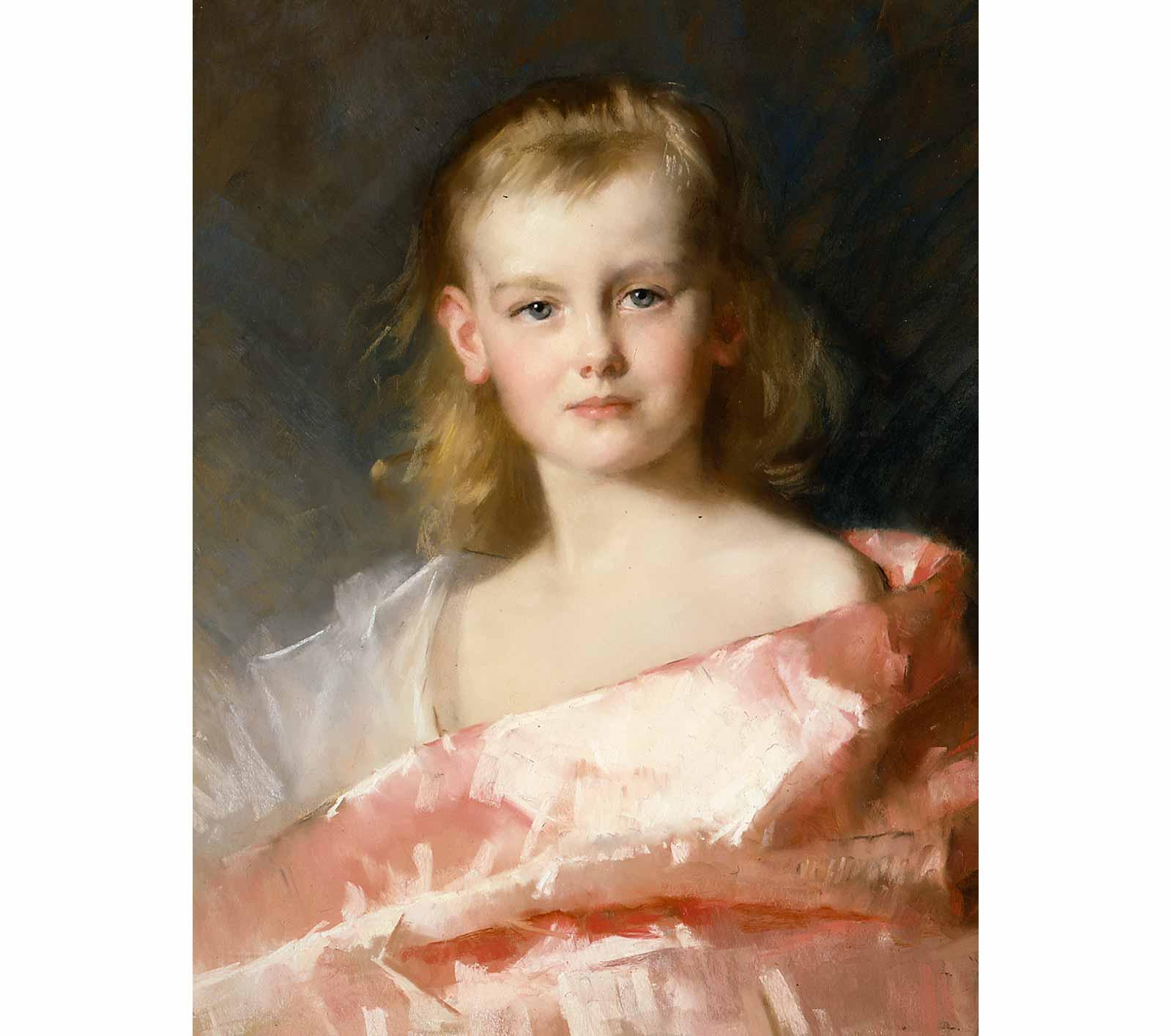

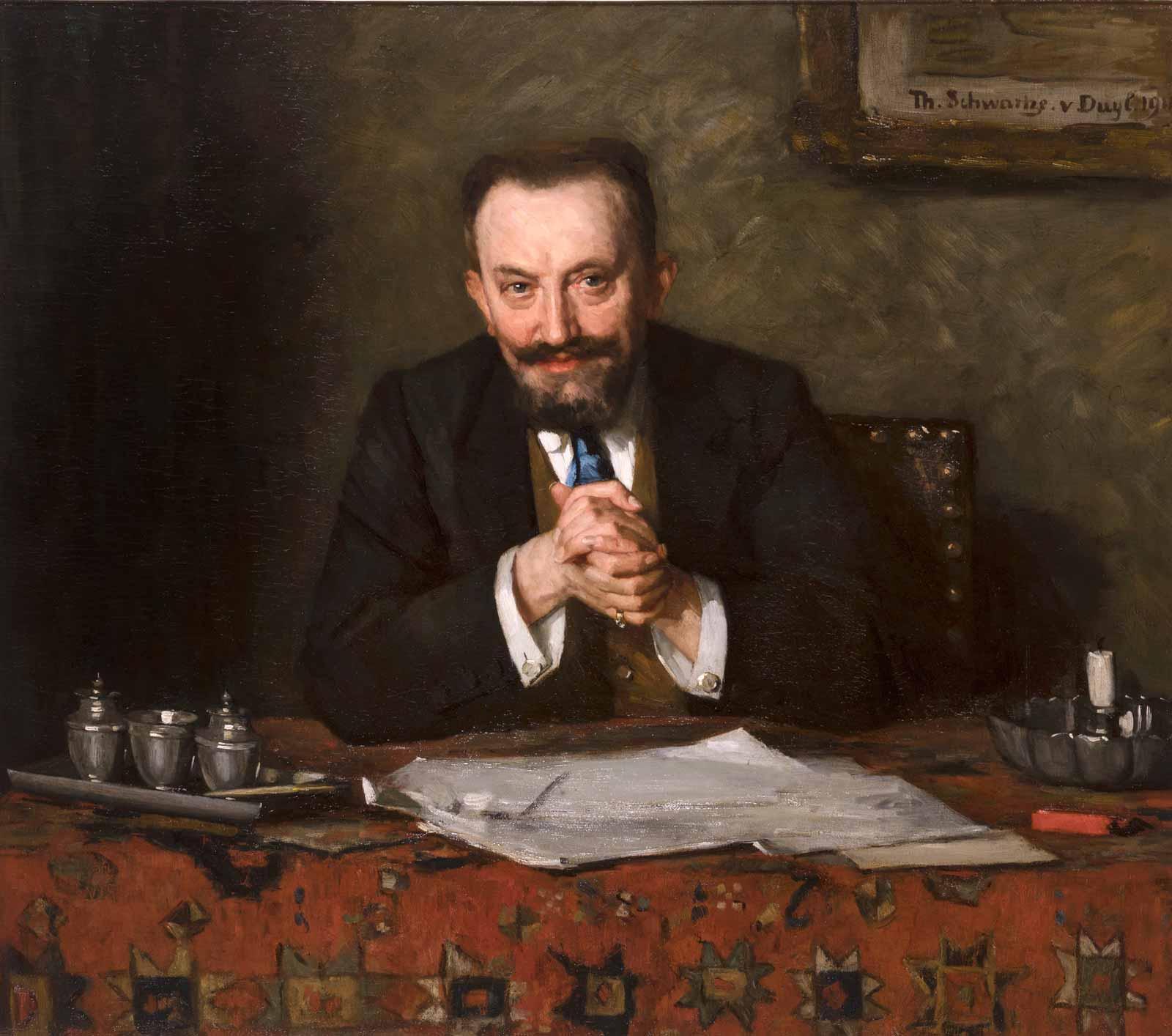

The artist stares hauntingly out at the viewer, paintbrush in one hand with the other looped through a paint-laden palette. The background of this canvas at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum is bare, and we’re drawn to the painter’s tools: eyes, brush, pigments, and a rag at the ready. The artwork doesn’t depict beloved Post-Impressionist Vincent Van Gogh, though. This is a self-portrait by his Dutch compatriot and contemporary, Thérèse Schwartze, a successful portraitist between the late 19th century and her death in 1918. Schwartze was in high demand in her day but is now fairly obscure, and her likeness was part of the In the Picture group exhibition of artist portraits at the museum.

“The self-portrait as an artist was a significant statement for women,” explains Lisa Smit, curator at the Van Gogh Museum. “Only a handful of female portrait painters were active professionally in the 19th century, one of whom was Schwartze–a celebrated artist nicknamed the ‘Queen of Dutch Painting’. Schwartze approaches the viewer confidently and with the hint of a smile, although she thought she had presented herself as ‘freckled, small, skinny and pale’.”