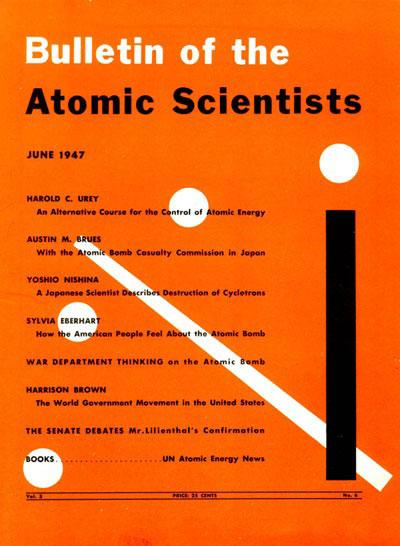

It is two minutes until midnight. On January 24th, 2019, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists unveiled this most recent shift of the minute-hand of their Doomsday Clock. The clock maps humanity’s trajectory towards an apocalypse most likely brought on by nuclear warfare or impending and irreversible climate change. Each year, scientists and scholars of the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board convene to decide whether the clock’s hand will be moved forward, towards apocalypse, or back, and away from imminent danger.

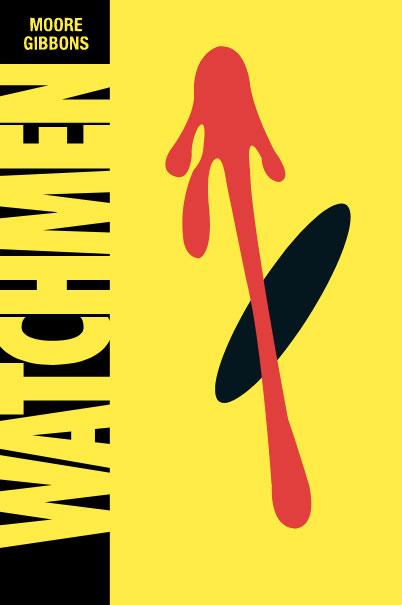

Say the phrase “Doomsday Clock” today and a lexicon of images are conjured: a fiery montage of voluminous mushroom clouds á la Dr. Strangelove, coastal cities swamped under rising sea waters, end-of-days preppers stockpiling canned goods in plush underground bunkers, and always, the ever-present minute-hand, counting down the march toward the end. This ticking minute-hand has been taken up and disseminated in a variety of popular cultural forms, from the main motif of the Watchmen comic series, to the titular image of The Smashing Pumpkins’ song, “Doomsday Clock.”

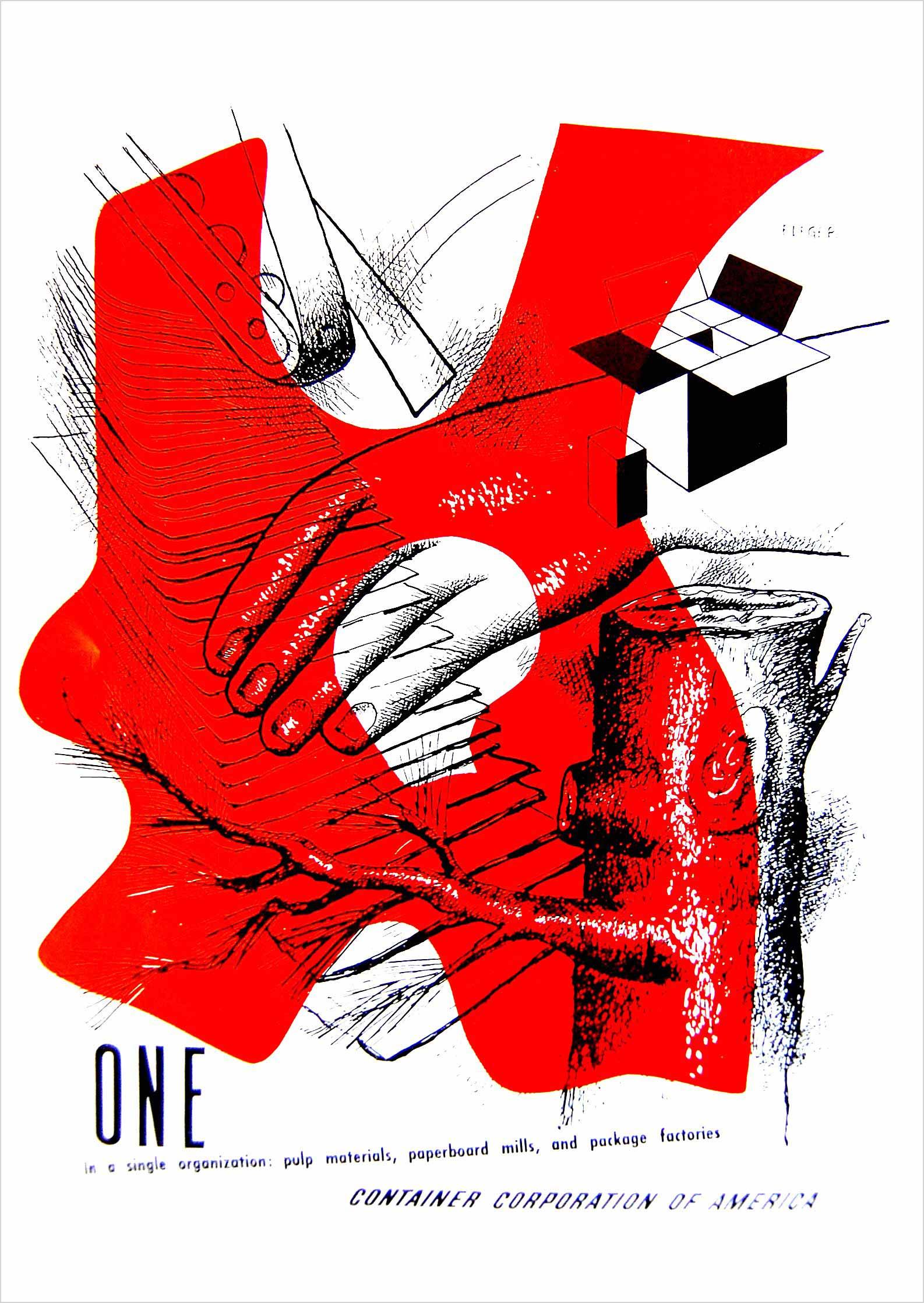

It is a lesser-known fact that the origin story of the Doomsday Clock begins in Chicago in 1947, and is closely linked to the history of mid-century modern graphic design. In the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the United States in 1945, a concerned group of Manhattan Project scientists realized their role in creating this potentially world-ending weapon and formed the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Their mission was to warn and educate the public about the dangers of nuclear technology, which they did in part through a monthly publication.