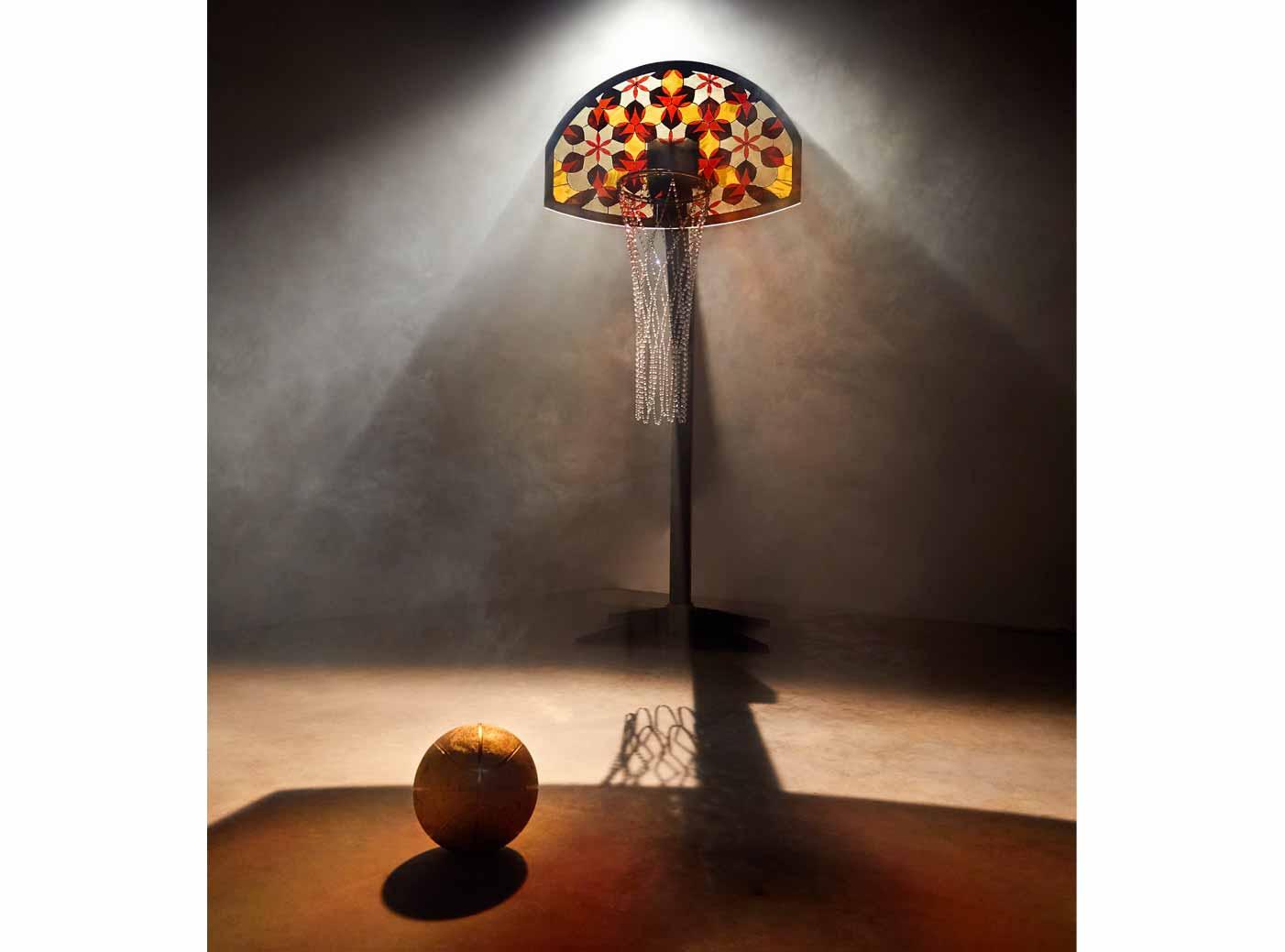

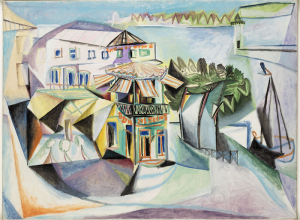

At first glance, basketball and art may seem like an unlikely combination. But when Emily Stamey was a graduate student at the University of Kansas—the coaching home of the game's Canadian inventor, Dr. James Naismith—she studied two basketball pieces: Jeff Koons' One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank (Spalding Dr J Silver Series), and Higher Goals by David Hammons. “I was struck by what a compelling comparison they made, and the seed of an idea for this show was planted. I've been mentally ‘collecting’ basketball artworks ever since,” shares Stamey, now curator for the Weatherspoon Art Museum at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

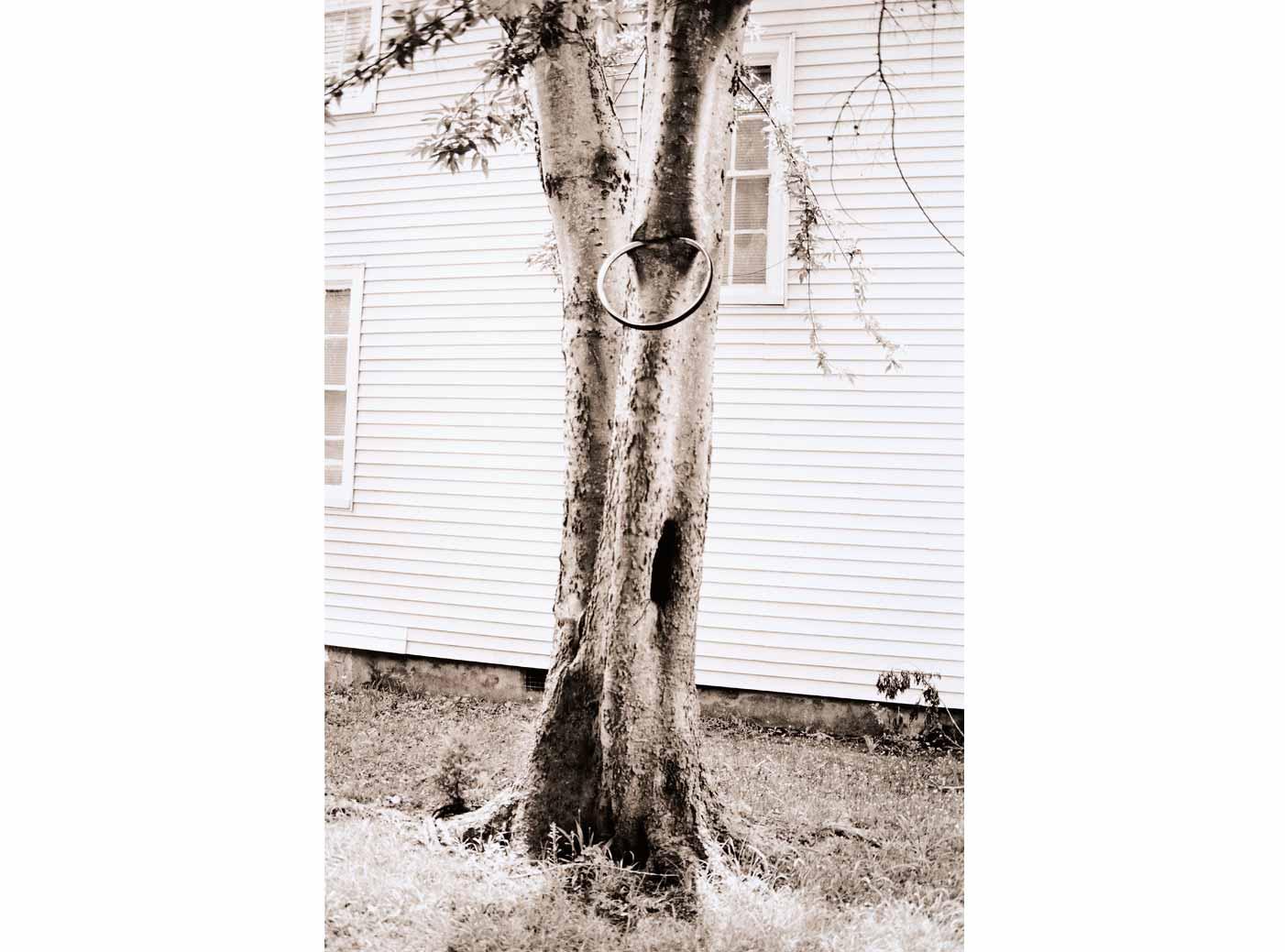

The resulting exhibit is To the Hoop: Basketball and Contemporary Art. An edition of the same Koons piece that first inspired Stamey was on display. A photograph by Hammons, Money Tree, is also included.

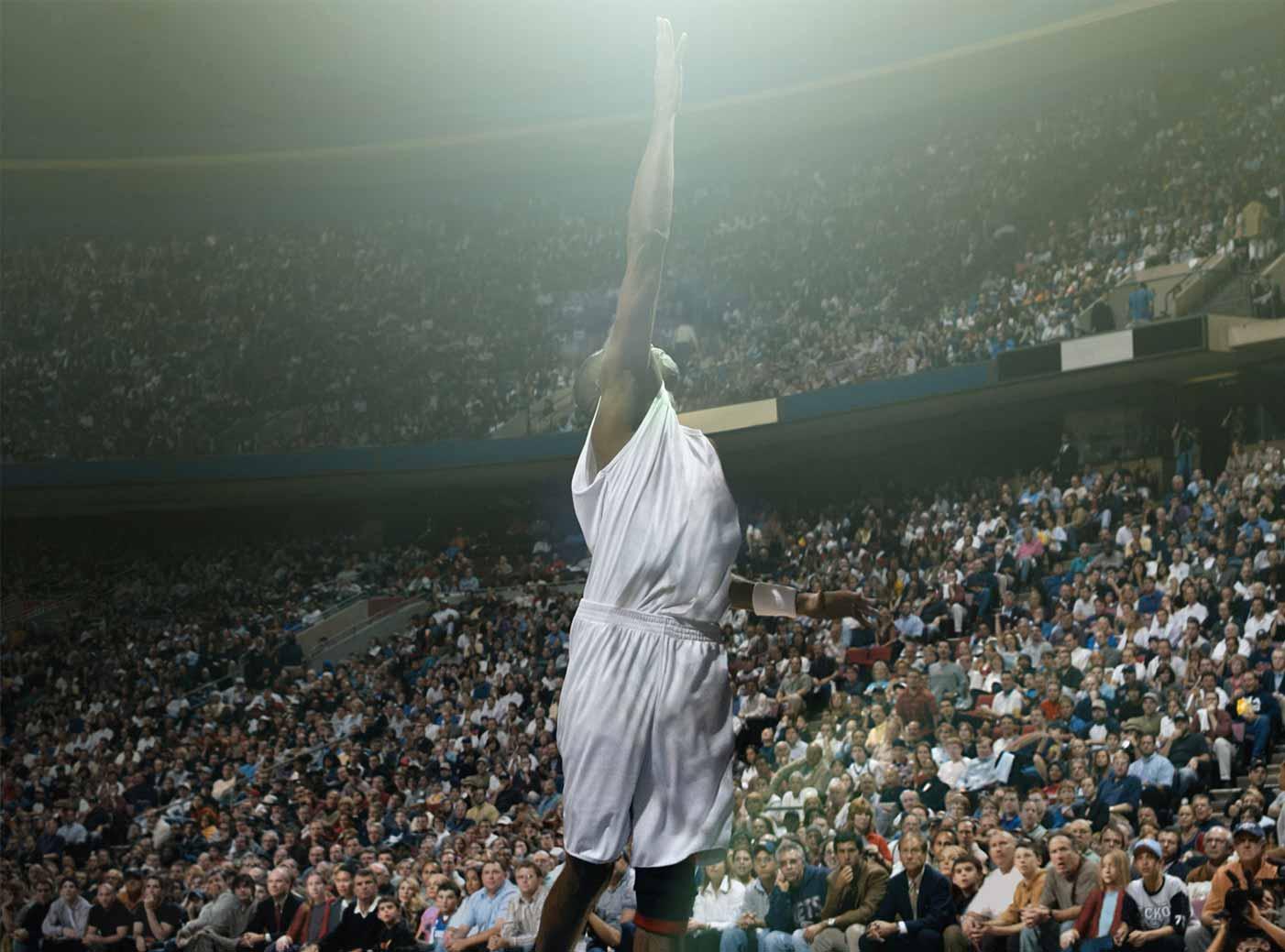

Through the artworks she has compiled, the curator reveals three complex conversations, including race and gender issues as well as metaphysical themes. Artists juxtapose opposites and strip down stereotypes to reveal layers, all focused through the lens of this world-famous sport. Stamey and participating artists Gina Adams and André Leon Gray shared some of their insights with Art & Object.

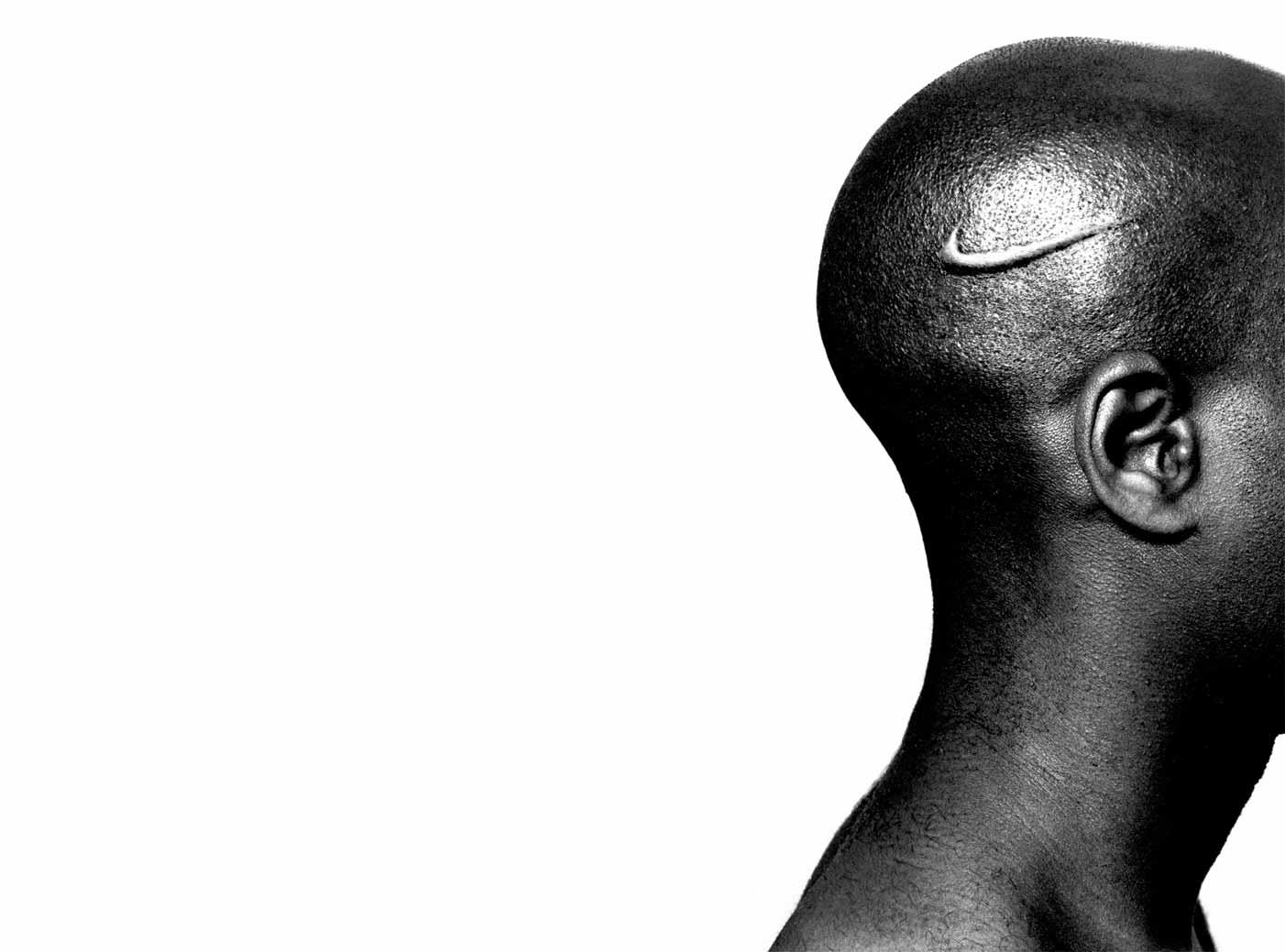

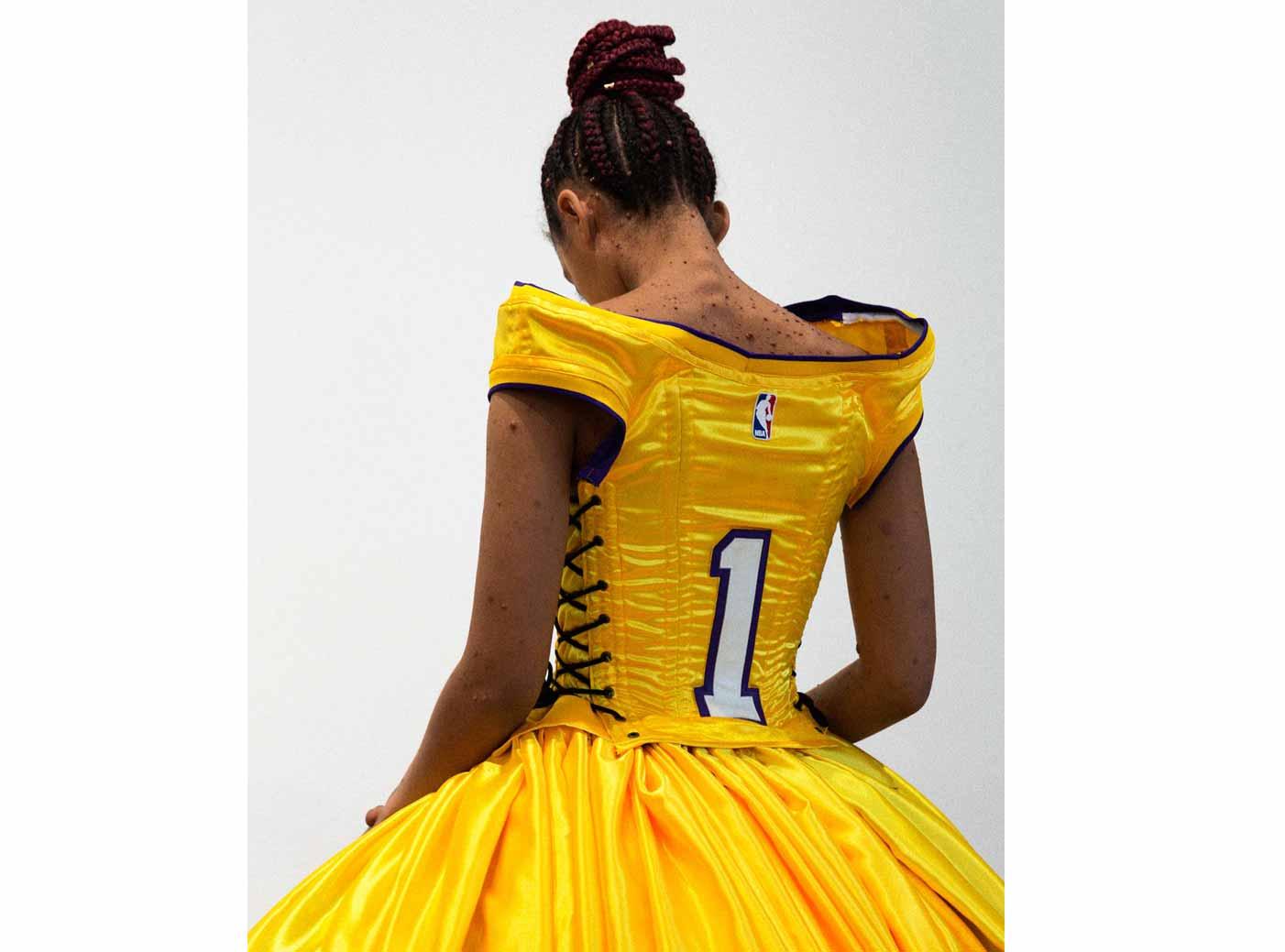

“There are so many social issues that the artists are addressing,…that's where the complexity comes in,” explains Stamey. She points out that in 2018, 56 percent of NCAA Division I players and 73 percent or more NBA players were African American. “Race looms large, but it is never the singular subject. …Hank Willis Thomas' Branded Head is about the commodification of black male bodies,…as well as the ways in which [we]…choose to brand ourselves.” In his video Practice, Mark Bradford attempts to play basketball in a cumbersome hoop skirt, exploring gender and racial stereotypes. “In part, it's a response to assumptions he faced as a kid that—because he is male, black, and tall—he should be a basketball player. But [the artist] also takes on the idea of endurance…,” explains Stamey.