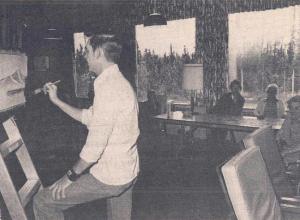

The answer to those questions lies within the walls of the retrospective, “Henry Taylor: B Side,” which was first organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles by senior curator Bennett Simpson. This past fall, the show traveled east to the Whitney Museum of American Art in a larger setting with more paintings, organized by curator Barbara Haskell. This expanded version of the original exhibition features over seventy canvases made from 1991 to 2022, alongside installations, sculptures, and a special wall drawing made by Taylor in the days leading up to the opening. The show is up until January 28, and it’s one that you don’t want to miss.

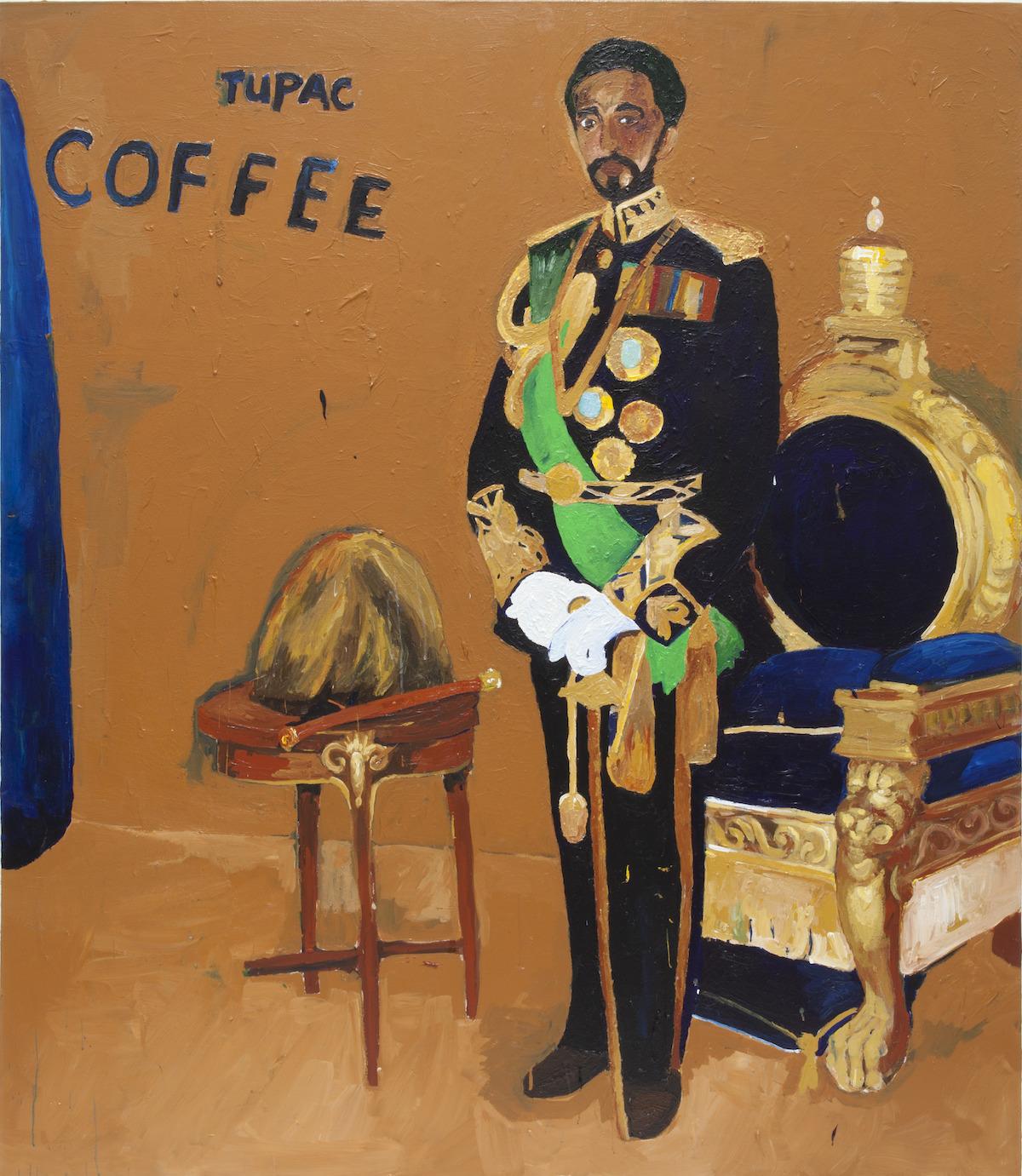

Henry Taylor (b. 1958) was the youngest of eight children. Always one for a good joke, Taylor likes to call himself “Henry the Eighth.” A work early on in the exhibition plays this up even further: a self-portrait in profile, Taylor depicts himself against a golden, ornately decorated ground in a red robe, a livery collar bedazzled with jewels, and his hand grips a golden scepter.

Untitled (2021) is a direct reference to a portrait of King Henry V of England. Here, we see what will become commonplace throughout the exhibition: Taylor’s stylized handling of paint combined with humor and a cold reality. Not only does the work function as a self-portrait, but the piece also reimagines the heritage of the British monarchy, suggesting a reshaping of the dynamics of representation.