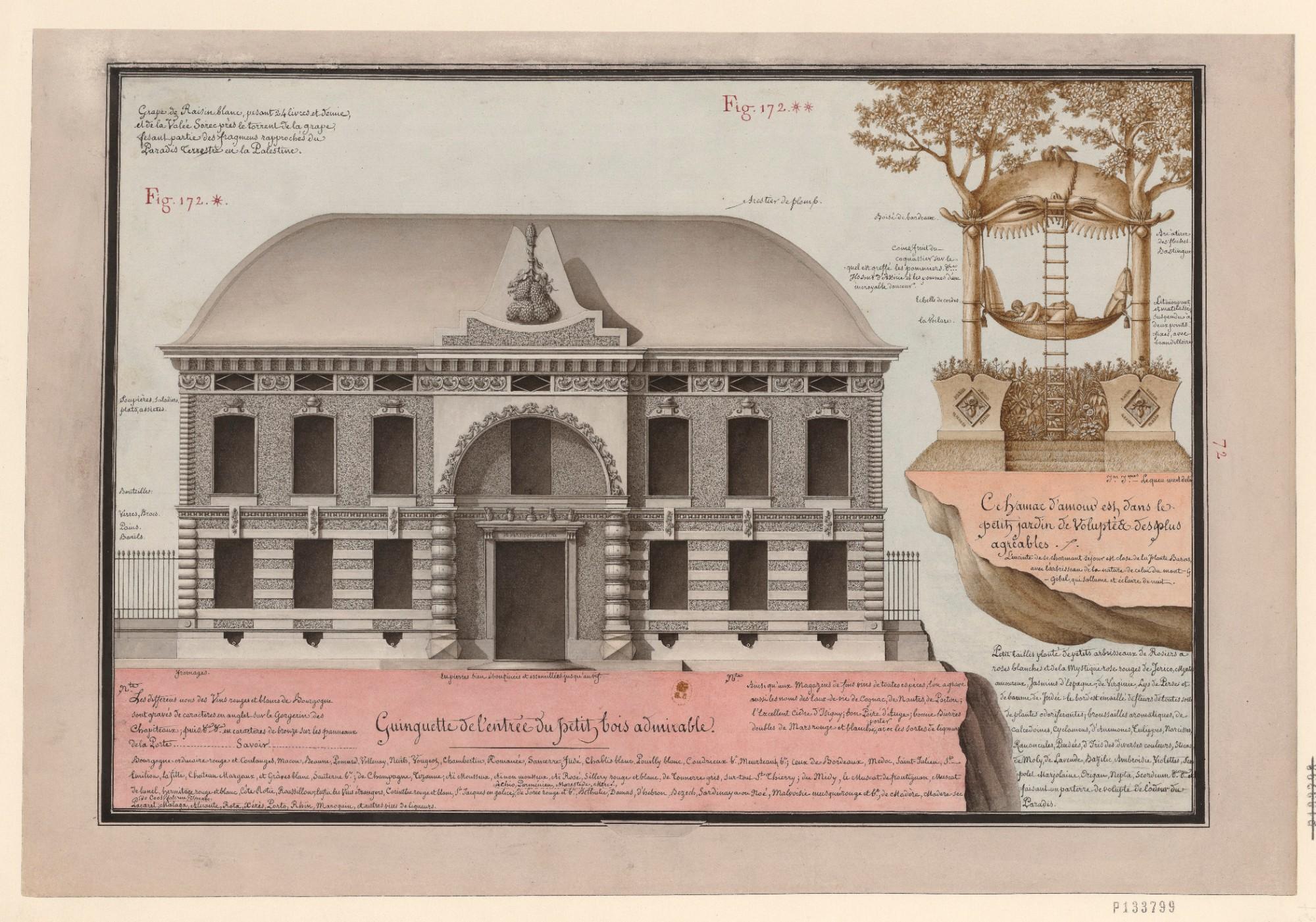

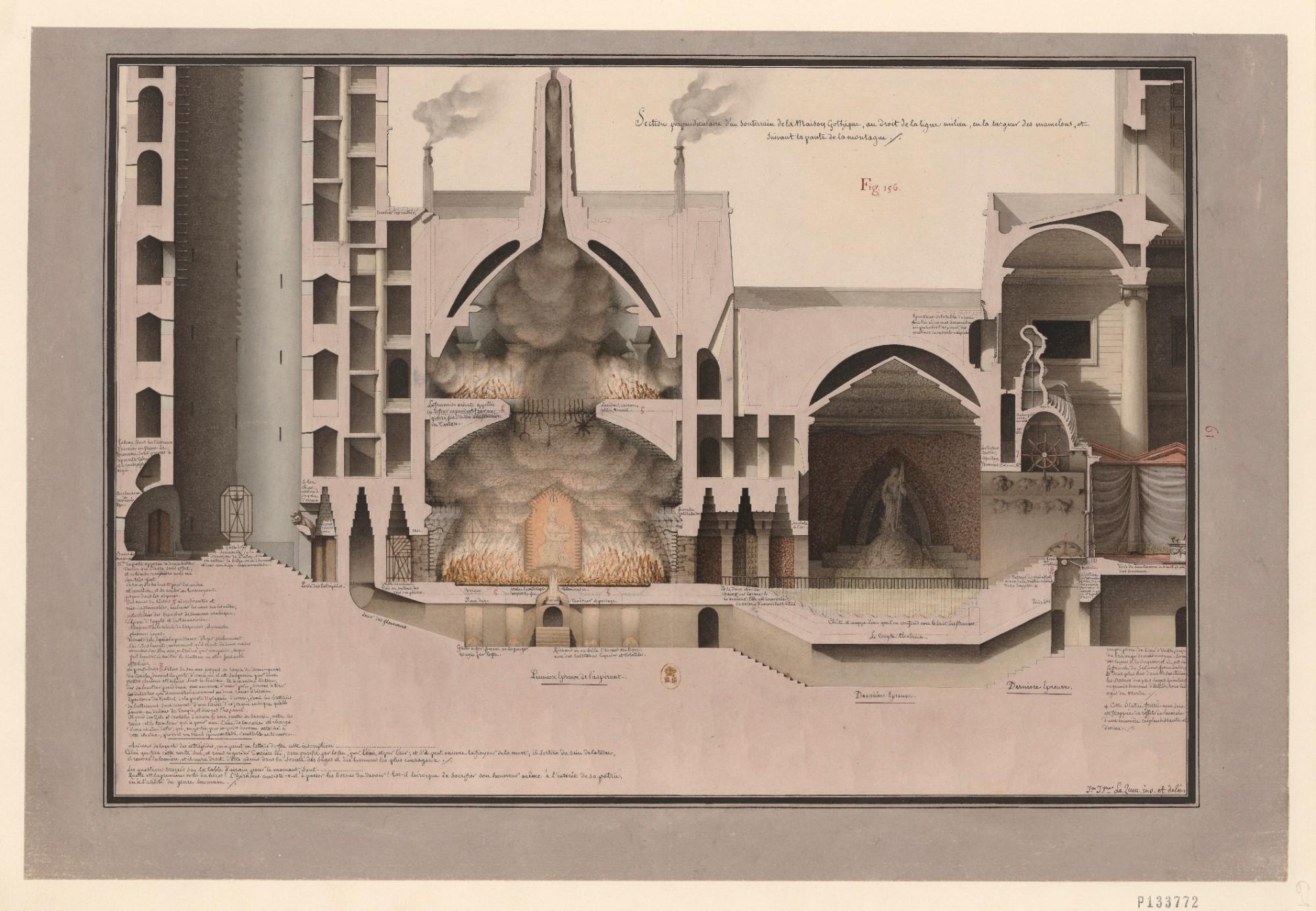

Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect, on view through May 10 at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, features around 60 of his drawings. It follows a version of the exhibition at the Menil Collection in Houston and the Petit Palais in Paris.

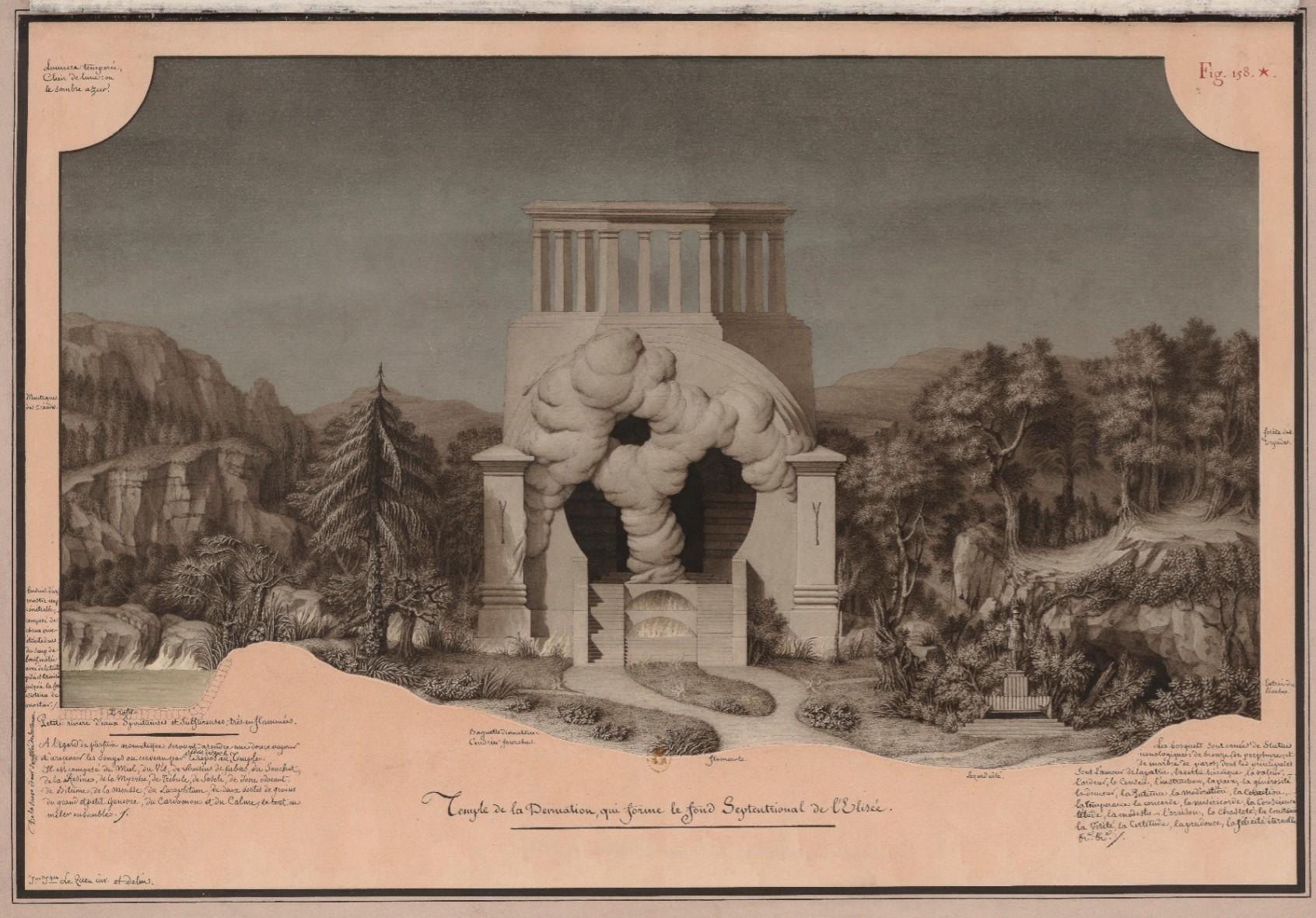

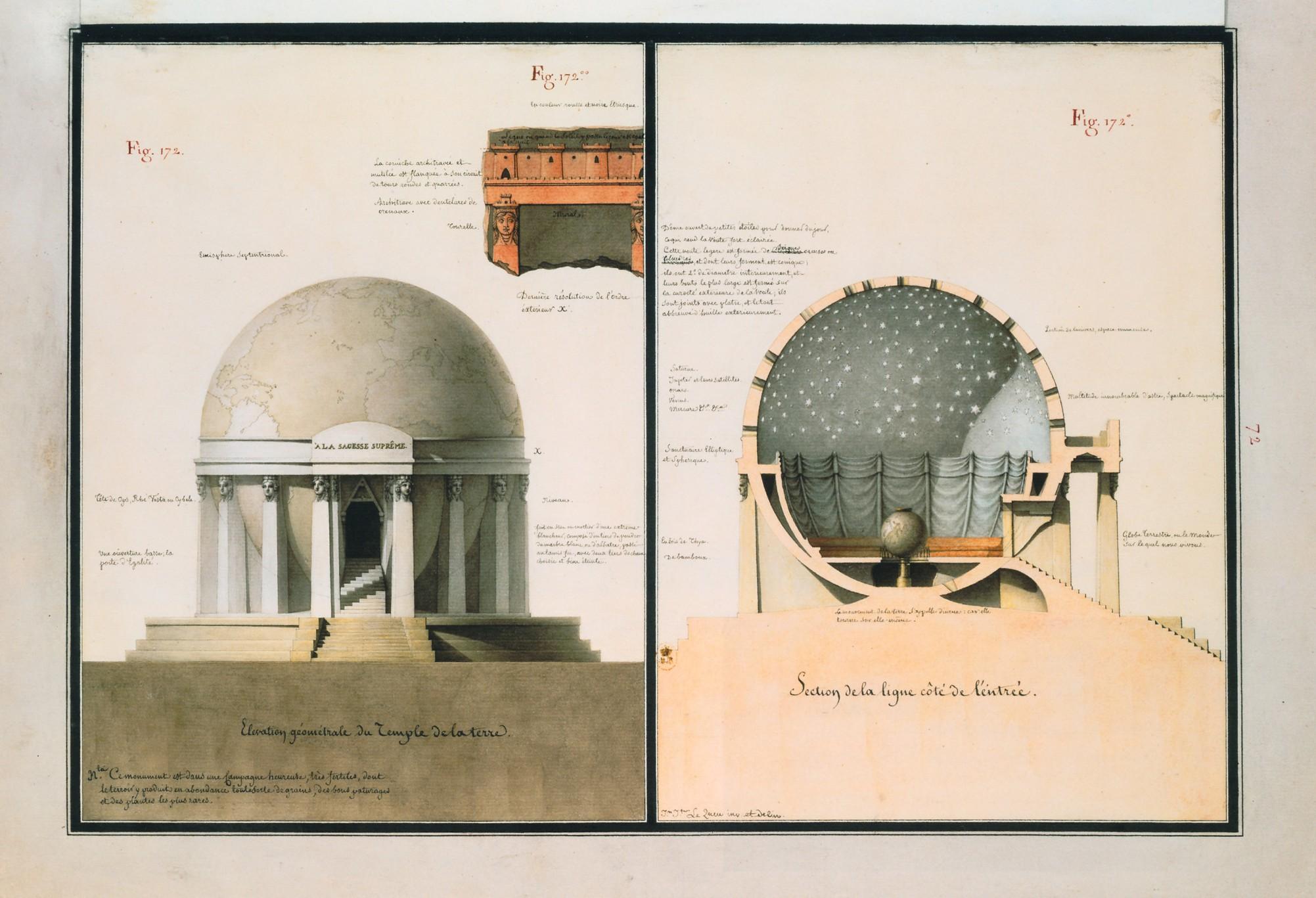

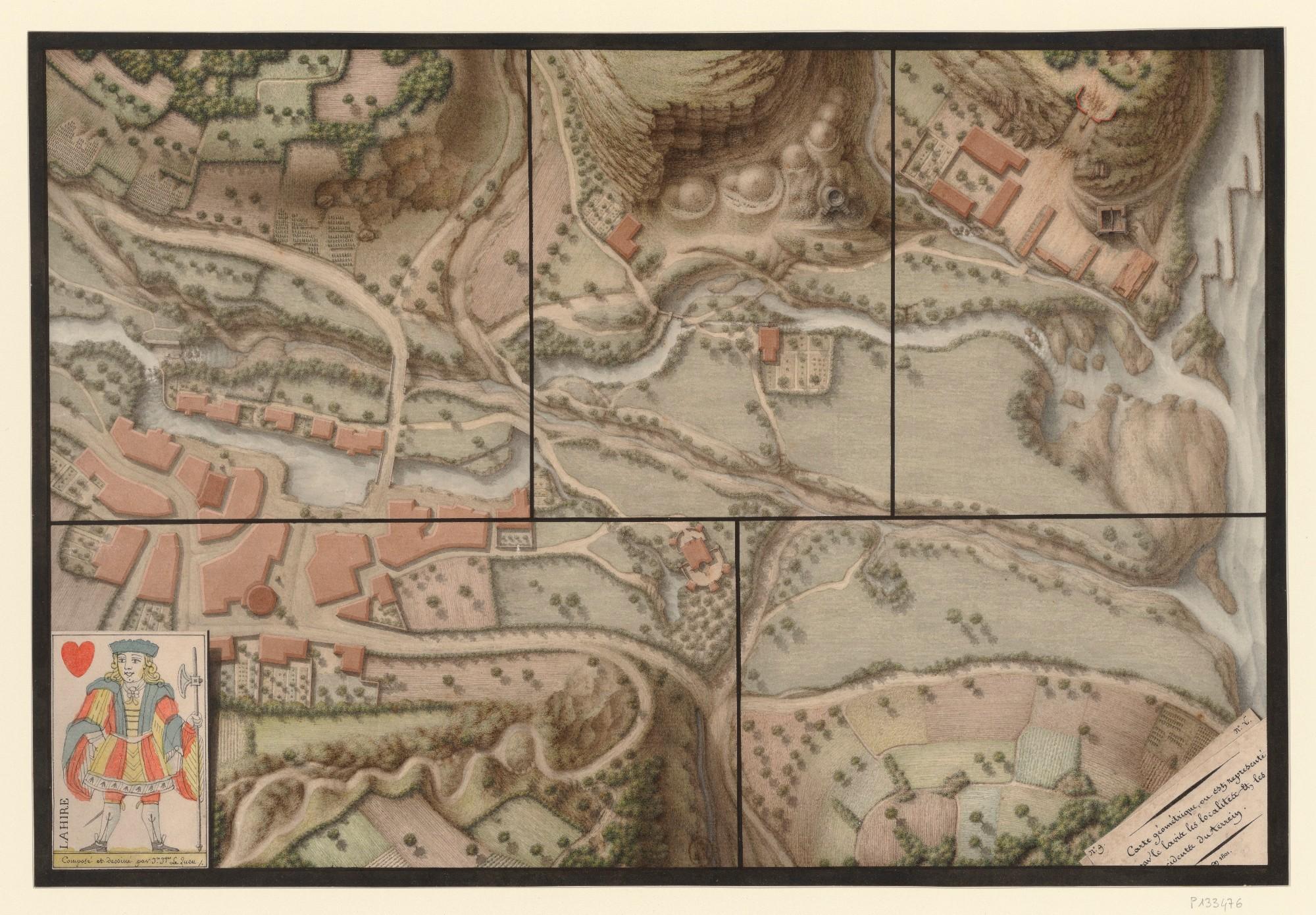

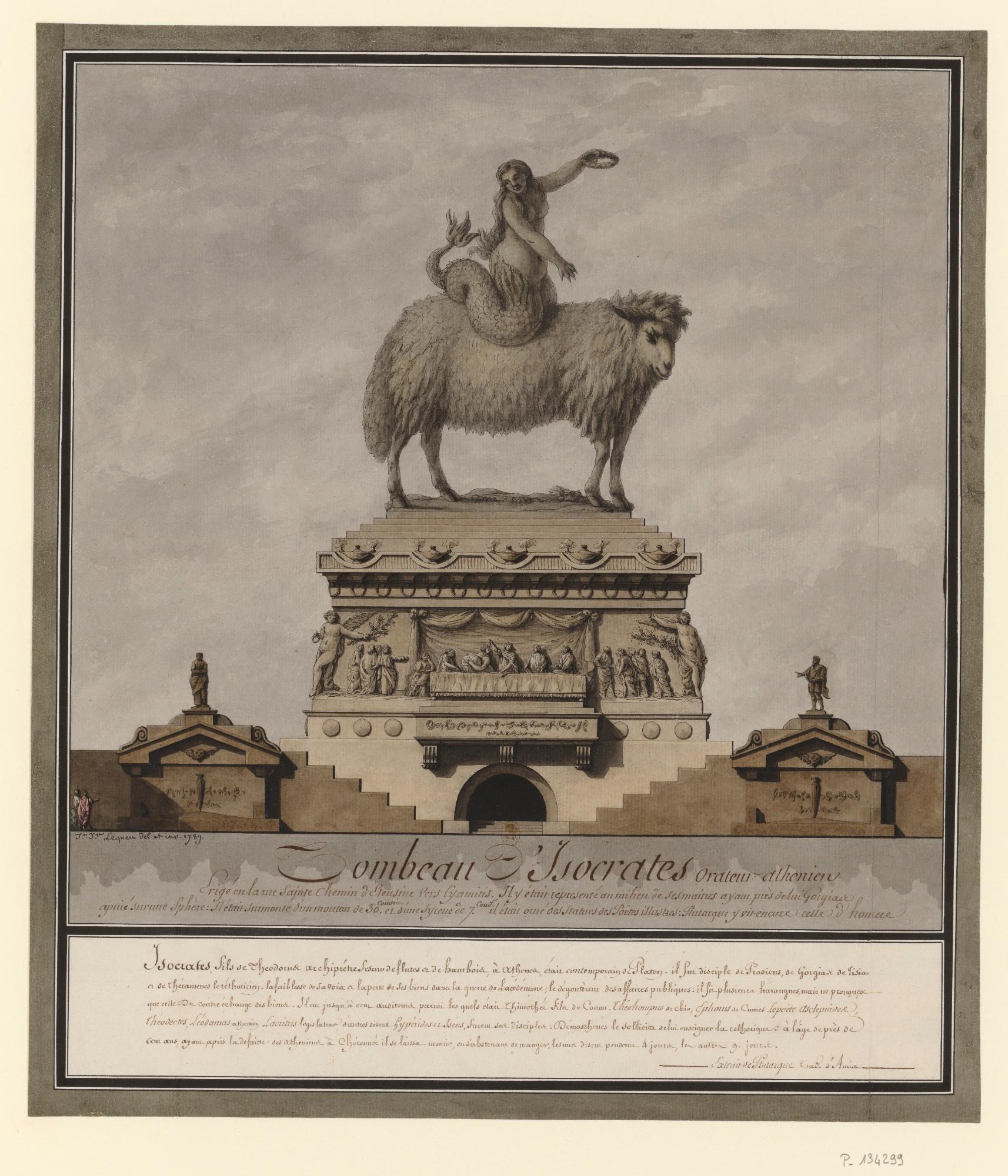

Rendered in pen and ink with wash and watercolor, Lequeu’s subjects range from eccentric ideas including a stable shaped like a colossal cow and theatrical structures such as one for initiation into a secret society to erotic drawings where Lequeu meditated on the sculptural qualities of flesh. He brought together inspiration from human and animal anatomy and architecture from across the globe, whether Middle Eastern minarets or classical ruins, a mashup that was all the more remarkable for an artist who worked in solitude, rarely leaving his studio.