Impressionism is a French export almost as popular as cheese, champagne, and couture. Crowds line up around the globe to attend blockbuster museum exhibitions of those beloved late 19th century Parisian artists, who celebrated light, pure color, and bourgeois fun on their canvases. What art scholars are now recognizing is that this worldwide love affair with Impressionism isn’t a new phenomenon; back in the heyday of Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Berthe Morisot and Edgar Degas (among others), the French Impressionists were already cultivating a devoted international fan base.

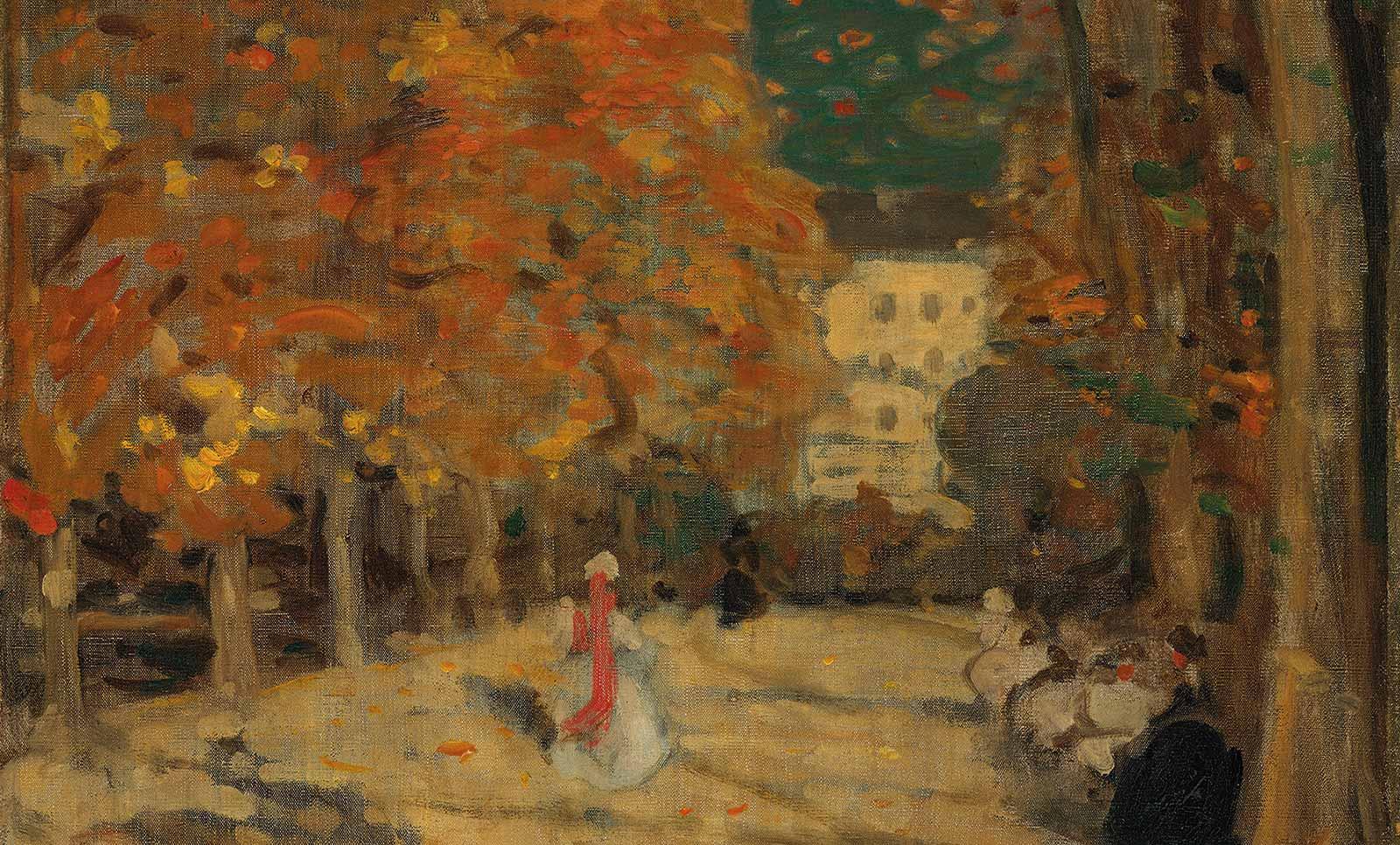

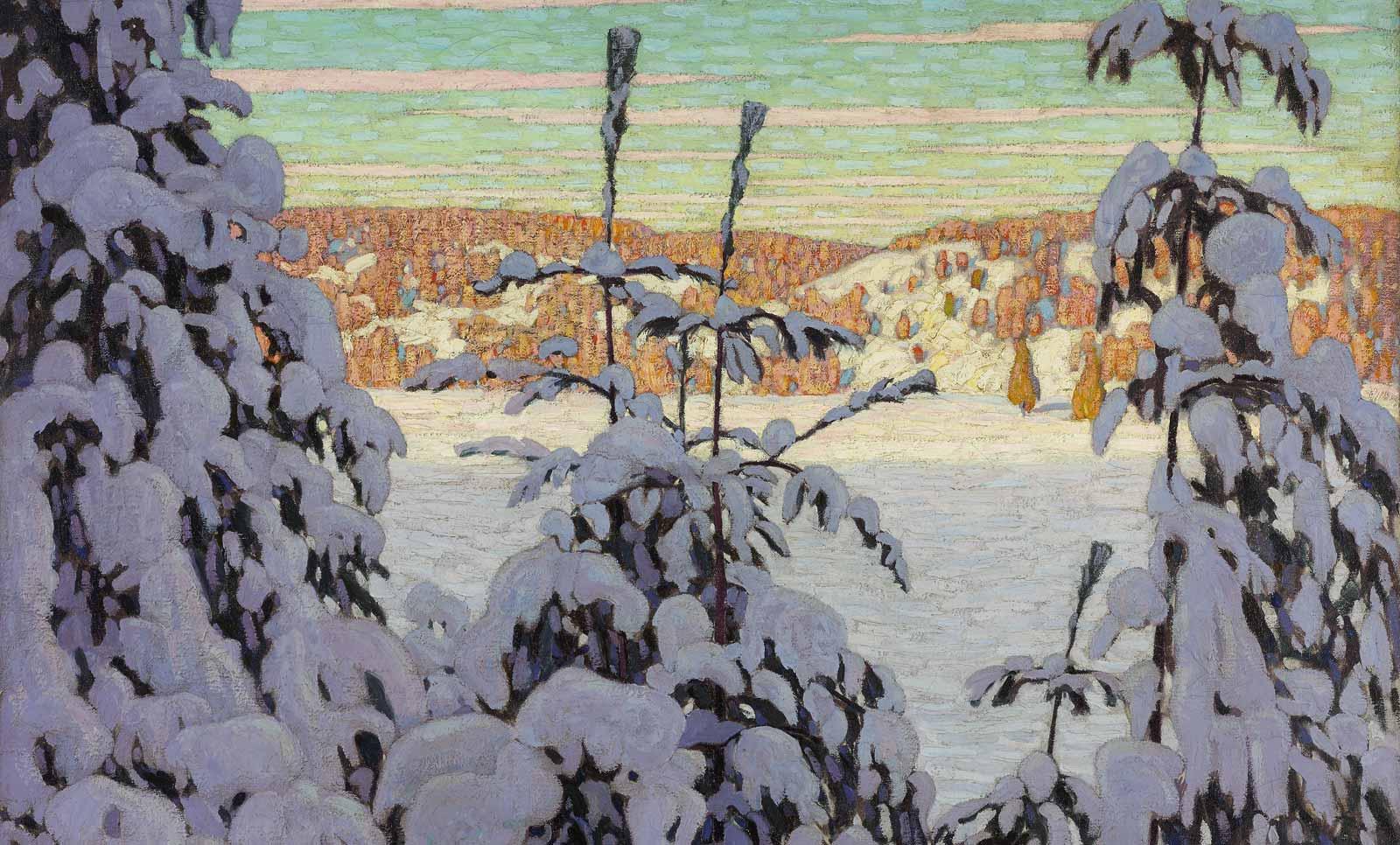

Impressionism was embraced in faraway places including Australia, Turkey, Mexico, Japan, and Scandinavia, spread by artists who pollinated their visual inspiration in Paris (then the supreme art capital of the world) and then planted the movement’s stylistic seeds back home. There they painted works related to the French originals, but tempered through distinctly local filters. Broken brushstrokes and unmixed color were applied to landscapes very unlike the rural countryside surrounding Paris, with artists figuring out how to transport what they learned in France to native subjects and audiences.

Global Impressionism is a recognized but understudied occurrence, and scholars are just scratching the surface of why this particular movement had such an impact as well as all the ways it was morphed abroad. “It took different forms in different places at different times,” Jennifer Thompson, curator of European art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and co-organizer of a recent symposium titled ‘Impressionism Around the World,’ told Art & Object. “Distilling that down isn’t possible today—we have to wait for at least another generation of scholarship.”

In the meantime, a traveling exhibition titled Canada and Impressionism organized by the National Gallery of Canada hopes to give the unsung Canadian Impressionists their belated moment in the pastel-hued sun. This first-ever exhibition devoted to the subject–now on view at the Kunsthalle Munich and continuing to the Fondation de l’Hermitage in Lausanne, Musée Fabre in Montpellier, and ultimately the National Gallery of Canada–has aggregated 120 paintings by 36 Canadian artists who traversed the Atlantic to study in Paris.