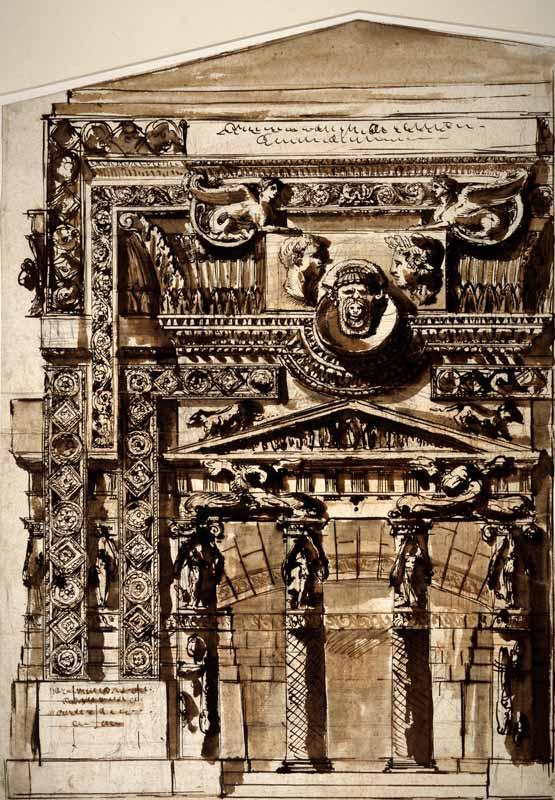

Giovanni Battista Piranesi was the greatest printmaker of the 18th century. Although he consistently signed his work ‘architetto,’ he is famous for his engravings of the monuments of ancient Rome, and in fact constructed only one building in his entire career. This building, the Church of Santa Maria del Priorato on the Aventine Hill in Rome, the monastery of the Knights of Malta, is not a masterpiece. The façade is overloaded with decorative details that break the grace of the architecture and confuse the eye. But not all architects can build, and Piranesi’s brilliance was on paper.

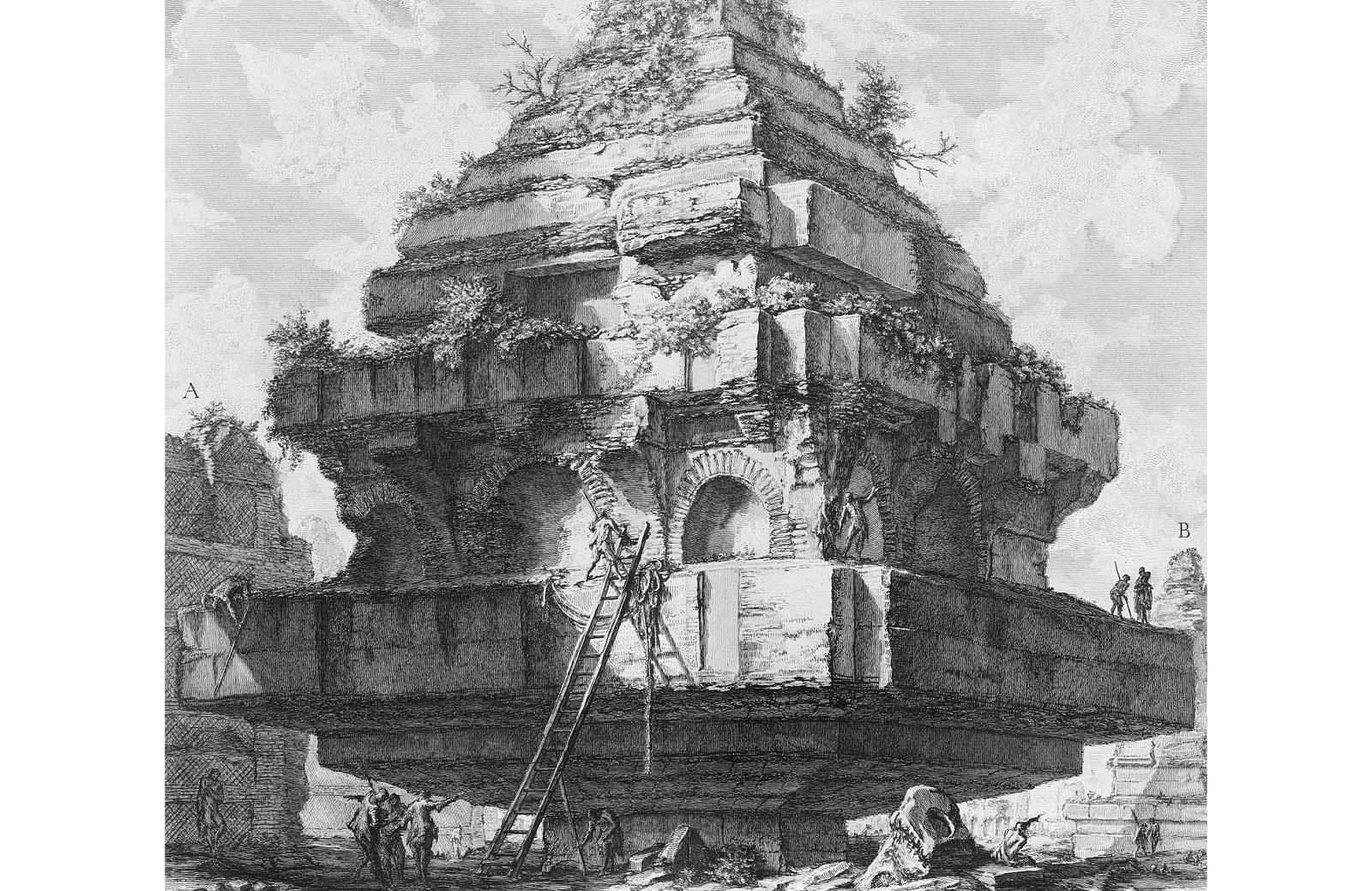

This year is the 300th anniversary of Piranesi’s birth and to mark the occasion the British Museum in London is holding an exhibition, Piranesi Drawings: Visions of Antiquity. While the most recognizable of Piranesi’s works are the evocative prints of Roman ruins in 18th century landscapes and the haunting etchings of grotesque prisons, the British Museum exhibition instead focuses on 51 ink and chalk drawings in its collection, highlighting his expertise as a draftsman.

On display are examples which span Piranesi’s working life from the 1740s to 1770s. We see the influence that Piranesi’s training as a set designer for the theatre in Venice had on his approach to perspective vistas, and the subsequent transformative impact that his move to Rome had on the subject matter of his work. The majority of the drawings are architectural scenes. While some are preparatory studies that were later worked up as engravings, most of the sketches are not directly relatable to known finished pieces. Indeed, Piranesi went against the common practice of making highly-detailed drawings for transfer onto copperplates (the method of engraving), remarking that, “if my drawing was finished, my plate would become only a copy.”