When is a Rembrandt drawing not a Rembrandt drawing?

When it’s by one of his students.

More than half the drawings in the 1957 Rembrandt catalogue raisonné by Otto Benesch, the venerated former director of Vienna’s Albertina museum, have in recent years been reattributed to the master’s students and colleagues.

Benesch was by no means the first to get it wrong. The false attribution dates back several centuries, according to Holm Bevers, the interim director of Berlin’s Museum of Prints and Drawings, which harbors one of the most important collections of Rembrandt drawings worldwide. “The confusion has historical roots in Rembrandt’s studio,” Bevers explains.

Rembrandt taught a procession of students between the 1630s and 1660s, of whom about fifty are known by name today. Some were, or went on to become, established artists—Ferdinand Bol, Willem Drost, and Samuel van Hoogstraten, for example. Others, like the city clerk Constantijn Daniel van Renesse, were amateurs lured by Rembrandt’s great reputation.

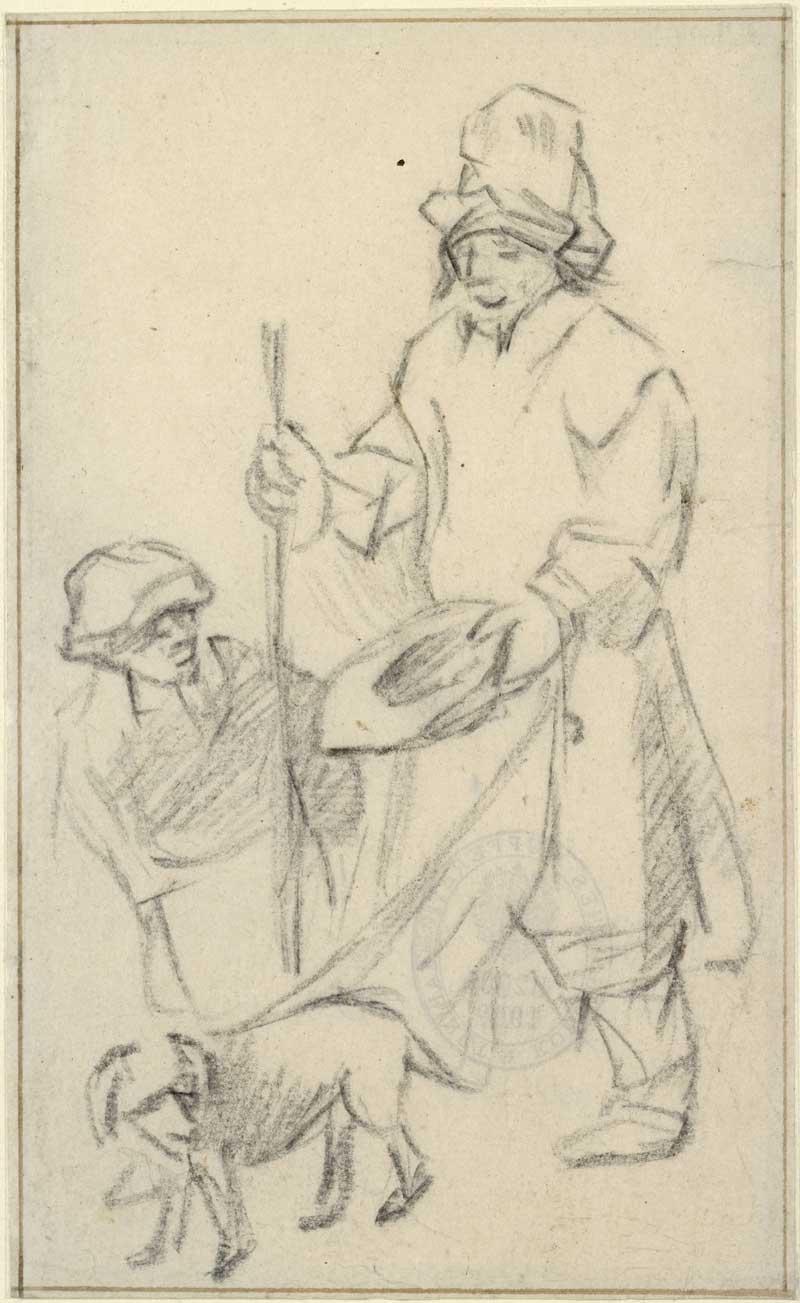

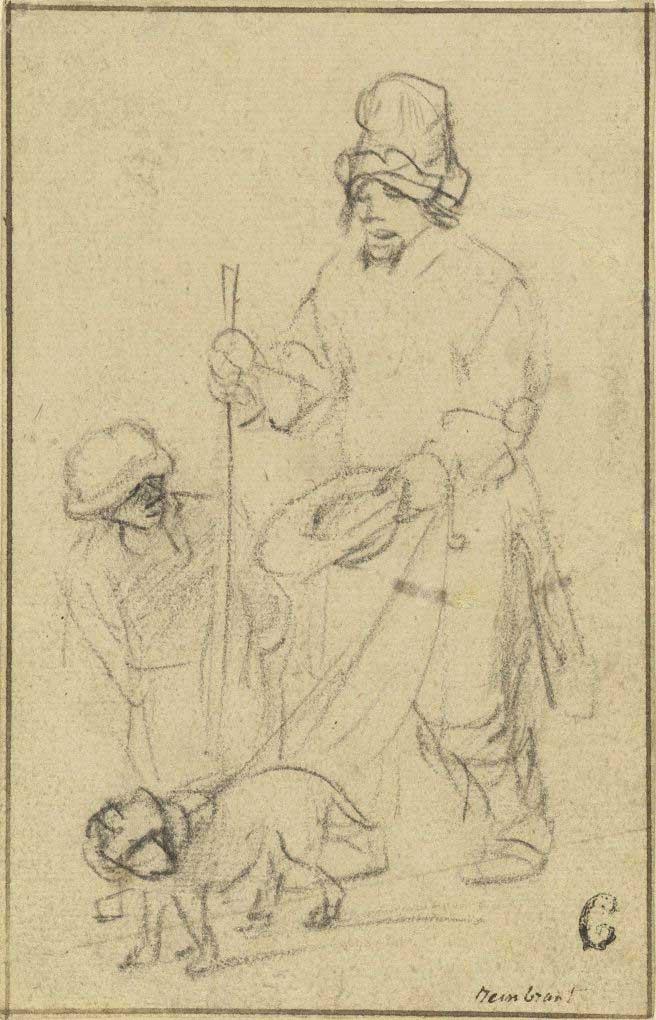

The students imitated Rembrandt’s style assiduously. They focussed on the same subjects at the same time and took expeditions with him to draw in the open air. After classes, the drawings were organized thematically in albums: landscapes, animal images, and biblical scenes, for example. Some of these drawings—there were as many as 2,000 altogether—entered the market as early as 1658, when Rembrandt went bankrupt and his possessions were auctioned to pay his debts. Others were sold after his death in 1669. Very few were signed, so collectors and dealers no longer knew which were by Rembrandt and which were by his students. Contributing to the muddle, some collectors later added Rembrandt’s signature to the drawings.

Bevers is one of a handful of experts who have been trying to unravel the tangle to establish which were by Rembrandt and which by his students. Similar work has been done by scholars in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Paris, London, Munich, Leipzig and Dresden. The Berlin Museum of Prints and Drawings “hadn’t really done anything about it since 1957,” Bevers says. “I said we should do something. The question of authorship is an important one.”

The work has yielded important results for Rembrandt scholars. “The image of Rembrandt is much more distinct,” Bevers says. “And we have a clearer picture of the pupils.”

Benesch’s catalogue raisonné featured 126 drawings from the collection of the Museum of Prints and Drawings. Bevers says 53 of these are not by Rembrandt. About 100 of the best drawings by artists from Rembrandt’s circle, some from the collection and others on loan, went on display in Drawings From the Rembrandt School alongside the master’s drawings.