Originally, the Muses were nine Greek goddesses, each one presiding over an art form. While three different muses each mastered a different form of poetry, curiously, the visual arts were not in their domain. Yet, the Graeco-Roman trope that had the poet start a poem by summoning the muse for inspiration has been broadly applied to other art forms.

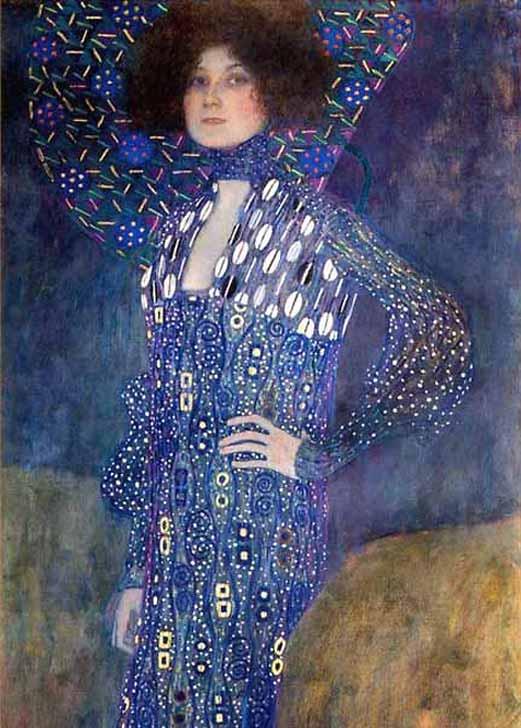

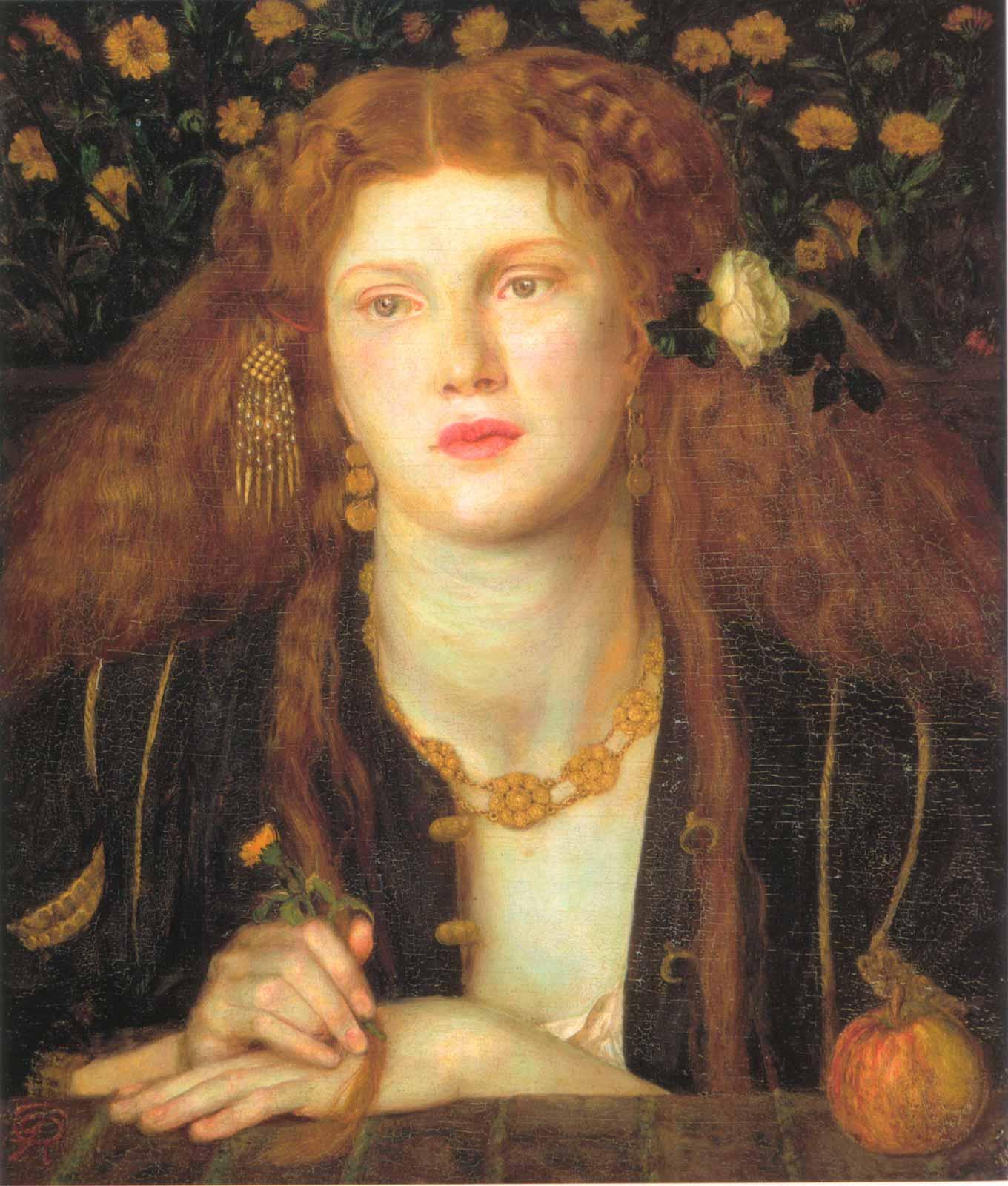

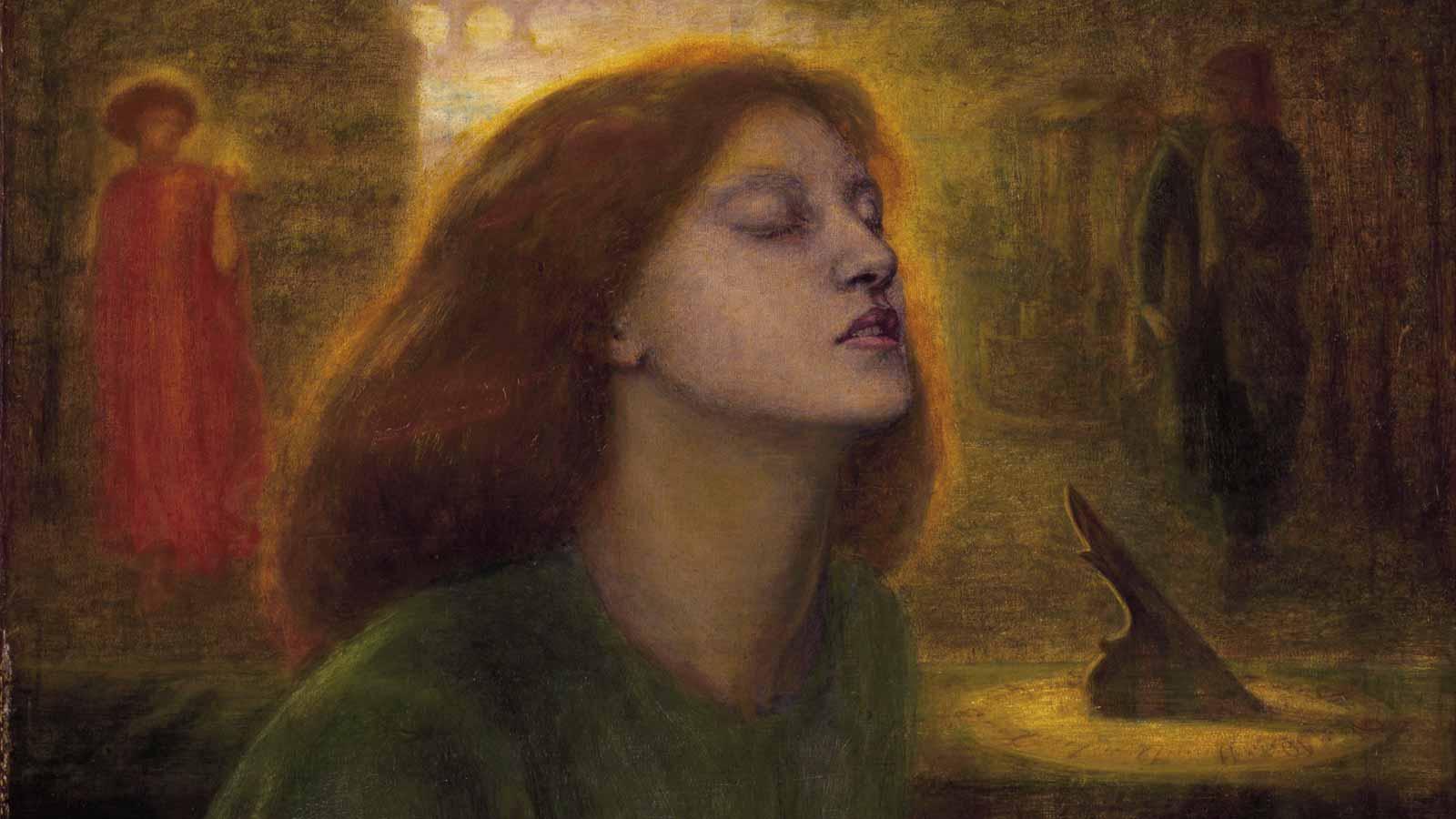

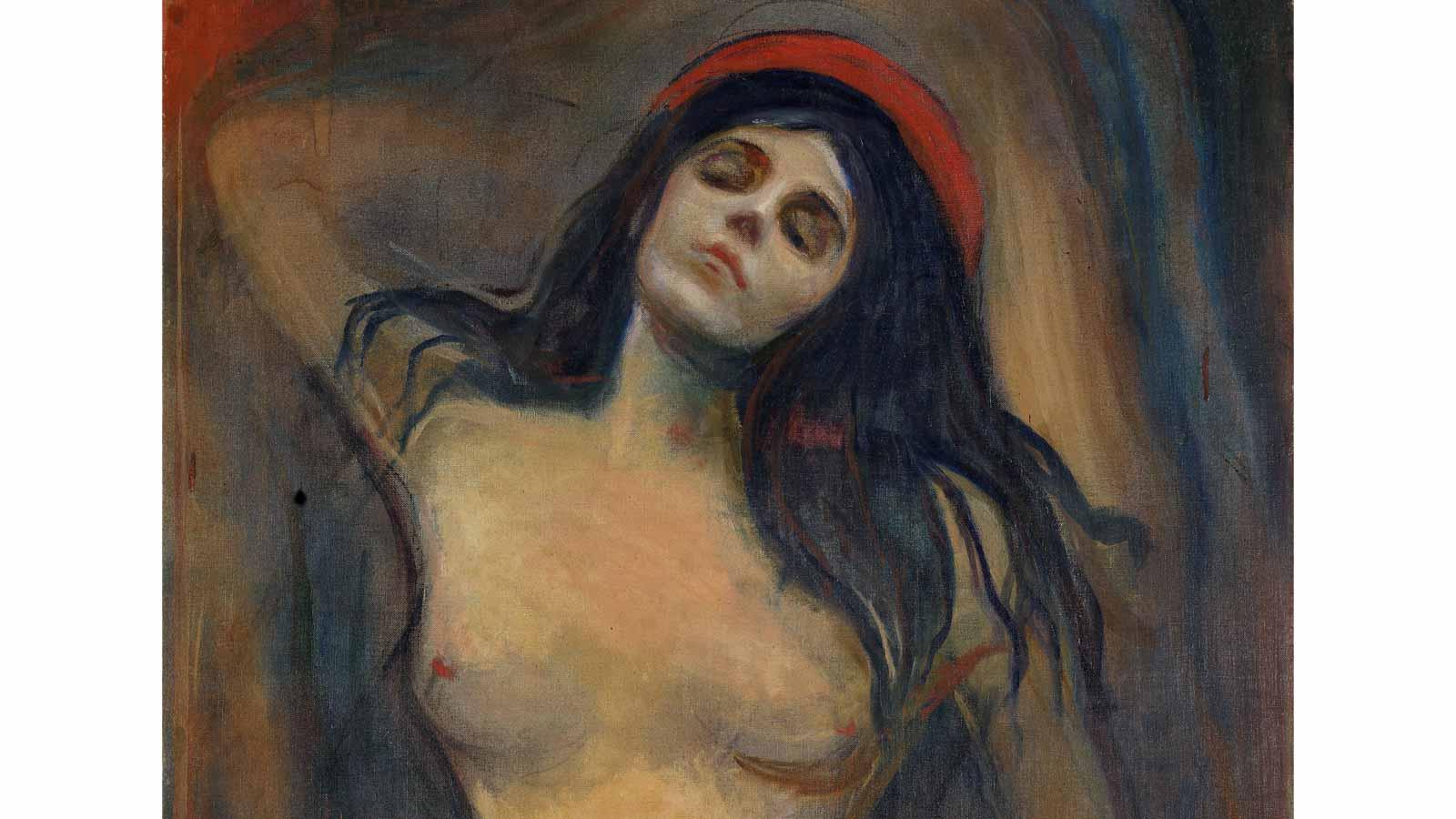

In the visual arts, especially the heteronormative ones, the term muse is quite gendered. “The muse in her purest aspect is the feminine part of the male artist, with which he must have intercourse if he is to bring into being a new work. She is the anima to his animus, the yin to his yang, except that, in a reversal of gender roles, she penetrates or inspires him and he gestates and brings forth, from the womb of the mind,” wrote the feminist author Germaine Greer.

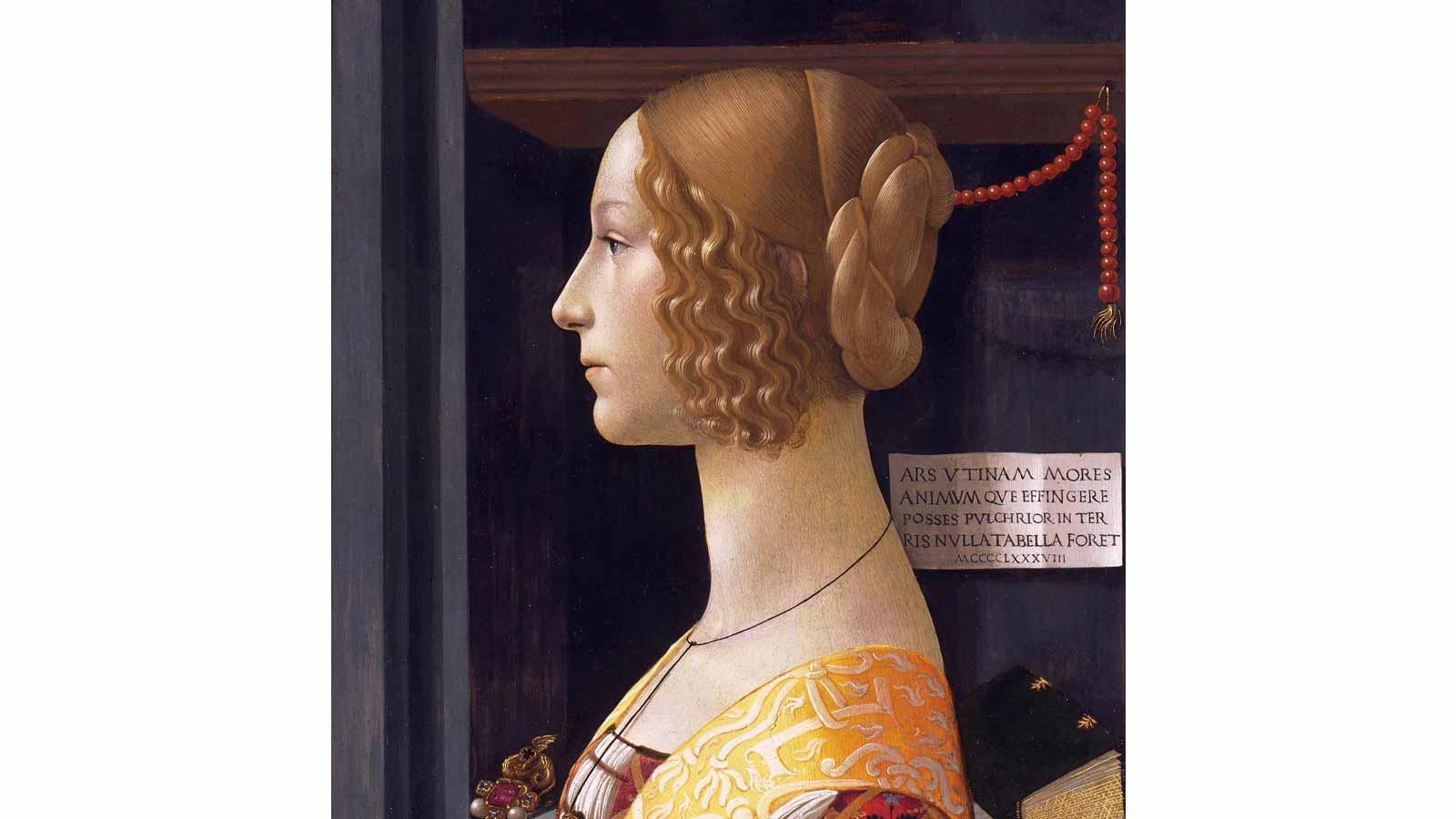

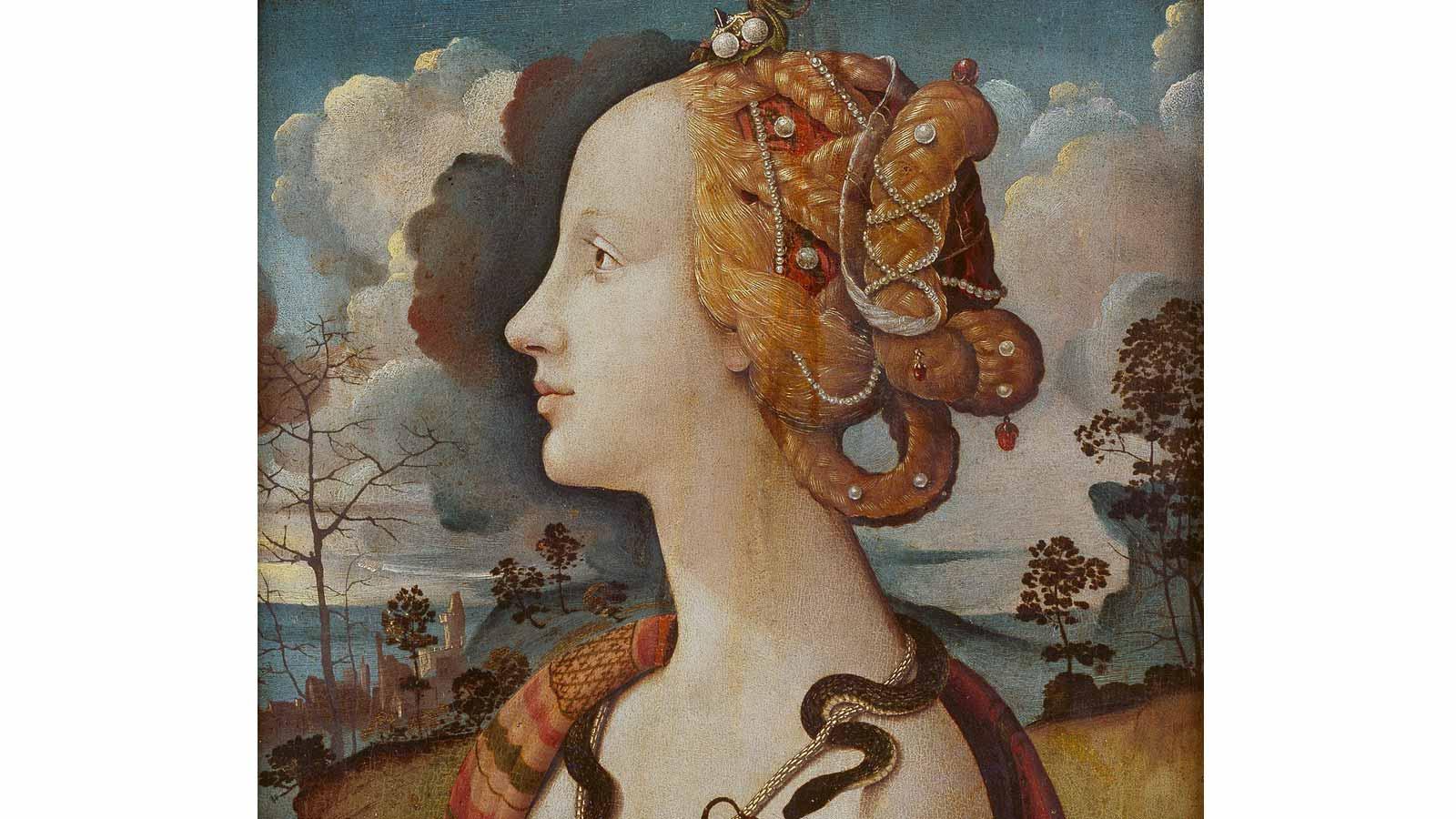

While we loosely use the word “muse” to describe an inspiration or influence behind an artwork, in popular culture, we are guilty of either idealizing a woman as a muse or downgrading an accomplished female artist to one. This still happens today, and has taken place for centuries.