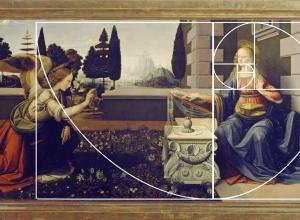

In the northernmost reaches of the Scottish North Sea, on the small, windswept isle of Lamb Holm, sits a pristine vestry at the intersection of religion, art, and war. Sixteen feet wide and 72 feet long, the structure features all the trappings of a humble house of worship. Sunlight seeps through a quartet of stained glass windows. Bespoke lanterns dangle above hand-wrought iron and brass candlesticks. Frescoes adorn the cobblestone walls, including a highly ornate rendering of the Madonna and Child.

But look closer, for this is no ordinary chapel.

The cobblestone walls are a trompe-l'oeil, nothing more than lines of pigment on bare concrete. The stained glass, upon closer inspection, is simply painted glass. Though the lanterns and candlesticks betray long days of painstaking craftsmanship, they, too, are made from used bully-beef tins and scavenged scrap metal––the only materials available to the roughly 500 Italian prisoners of war (POWs) that inhabited this island between 1942 and 1944.

Today, the Italian Chapel (as it is now known) is among the most prominent attractions to Scotland's Orkney Islands. More than 100,000 visit each year, drawn from every corner of the globe. Some come to marvel at the ingenuity of its artistry. Others in search of grace. Yet the longer these visitors linger, the more these virtues feel one and the same.

So it was, as well, for the men who built it.

The story of the chapel begins on a moonless night in October 1939. By now Britain had been at war with Nazi Germany for just over a month, though the absence of actual combat between the two powers made it easy to trust the fragile peace that still prevailed.

All that changed on Saturday, October 14. Just past 1 a.m., a German U-boat slipped through the murky waters off Lamb Holm and penetrated the confines of nearby Scapa Flow––the historic anchorage of the Royal Navy. Gliding over the waterlogged remains of the German high seas fleet––brought to Scapa and then scuttled at the conclusion of the First World War––the U-boat promptly locked its sights on the largest vessel in the harbor: the 30,000-ton battleship HMS Royal Oak. On board, more than 1,200 sailors slept soundly, blissfully unaware of the tragedy to come.

Moments later, the muffled explosion of a torpedo pierced the calm, then three more in quick succession. The ship shuddered. Then sank. In the span of 13 minutes, 833 lives were lost. Among the dead were 126 sailors under the age of 18––some as young as 14––the greatest single loss of boy sailors in the history of the Royal Navy. When alerted of the attack the next morning, Churchill wept openly. "Poor fellows, poor fellows," the prime minister murmured to his secretary, "trapped in those black depths."